The Social Network (2010) Script Review | #3 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Aaron Sorkin pens a tale about the founding of Facebook that is propulsive, riveting and electrifying.

Logline: As Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg creates the social networking site that would become Facebook, he is sued by the Winklevoss twins and partner who claim he stole their idea and by Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin, who was squeezed out of the business.

Written by: Aaron Sorkin

Based on: “The Accidental Billionaires” by Ben Mezrich

Pages: 163

I’ve read The Social Network screenplay as often as I’ve watched the film; that’s just a long-winded way of saying that it is one of my favorite scripts of all time, if not my all-time favourite. It’s clever, it’s entertaining, it’s withering, it’s sobering. In recounting the origins of how one undergraduate student built one of the 21st century’s most valued— and highly controversial—company, what emerges is a tale as old as Shakespeare. This is how Aaron Sorkin wrote the story about Facebook.

After getting dumped during a date turned disaster, undergraduate Mark Zuckerberg hacks the Harvard servers and creates a controversial website in which people can rate whether their fellow female students are attractive or not. This attracts the attention of twins Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, as well as their business partner, Divya Narendra. They have an idea for a social networking site that is exclusive to only those with a Harvard email address. But 39 days later, with Mark constantly flaking out on them, the Winklevoss twins and Divya are shocked to discover that Mark, with financial assistance from his best friend Eduardo Saverin, has created a social networking site called TheFacebook, one that requires using a Harvard email address to sign up for it. As TheFacebook—later revamped as Facebook— rapidly gains popularity on campuses, Mark and Eduardo clash over the site’s future; their friendship fractures further when Napster founder Sean Parker enters the picture. When a second round of angel investment is made into the company, Eduardo is stunned to learn that he will lose over 99% of his shares, effectively kicking him out of Facebook, leading to the end of his friendship with Mark.

Although The Social Network is a biopic, it eschews the conventions that often plague the genre. For one, it avoids the cradle-to-the-grave mentality found in many scripts based on a true story. Moreover, the origins of Facebook are shrouded in uncertainty and clashing recollections. Rather than pick one version, Sorkin opts to use three different sides of the story, using the technique of obfuscation used in classics such as Rashōmon and Citizen Kane. Who is telling the truth? Who is telling lies? Here’s the evidence, dear reader, you decide.

The script takes a non-linear approach to presenting the story. It jumps back and forth across time, using the framework of two depositions to structure the events surrounding those early days of Facebook. The main deposition involves Eduardo suing Mark for cheating him out of the company that he helped build; a second deposition is between Mark and the Winklevoss twins and Divya, who are suing him for stealing their business idea. If we break the structure down, it would look something like this:

THE PAST (the major part of the story)

Mark and Eduardo (how Mark built the site, how Eduardo financed it, and how the friendship crashed and burned)

The Winklevoss twins and Divya Narendra (how the trio try and fail to confront Mark and shut down Facebook) [starts on page 24, ends at page 129]

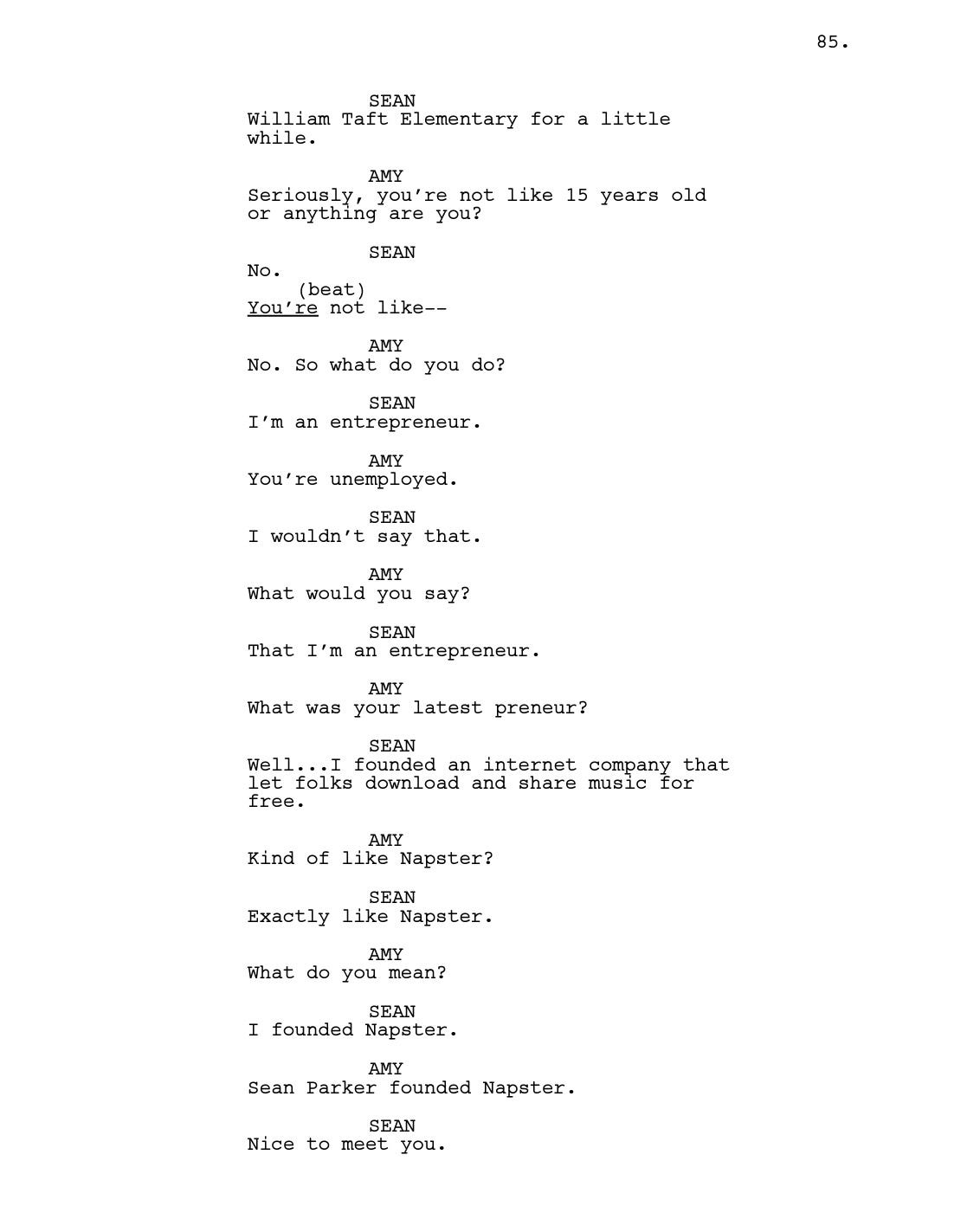

Mark and Sean Parker (how Mark met Sean, was persuaded to move to California, allows Sean to set up meetings with angel investments, and ultimately sideline Eduardo) [starts from page 99—though he appears as early as page 83—and ends on page 159]

THE PRESENT

The first deposition - Eduardo [starts at page 22, ends at page 150]

The second deposition - Winklevoss twins and Divya’s deposition [starts on page 26 and ends on page 75]

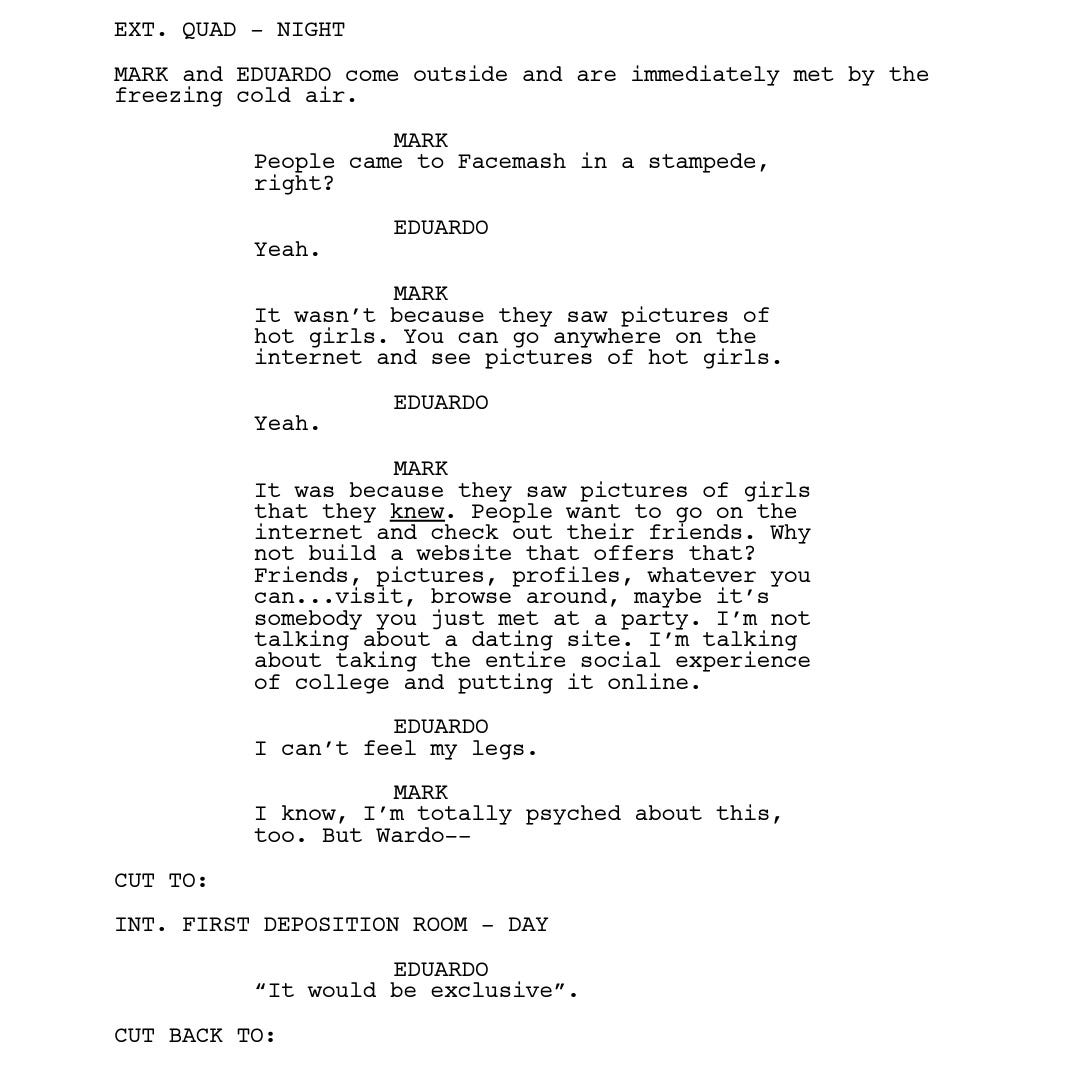

The depositions, coupled with the flashbacks, create anticipation. By telling us how it will end, we wonder how it ended so badly in the first place; namely, Mark and Eduardo’s friendship. The two were outcasts in their own way; Eduardo was the only friend that Mark had. Why would Mark screw him over like that? And that’s what the unreliability factor is there for— by avoiding a clear-cut definitive answer and refusing to endorse any version of the story, it creates an ambiguity that keeps us guessing.

Impressively, Sorkin does not use title cards or give cues to indicate time jumps between the depositions. He only mentions once in the script to indicate at which point in time the first deposition is taking place; but for the viewer, they would have to guess.

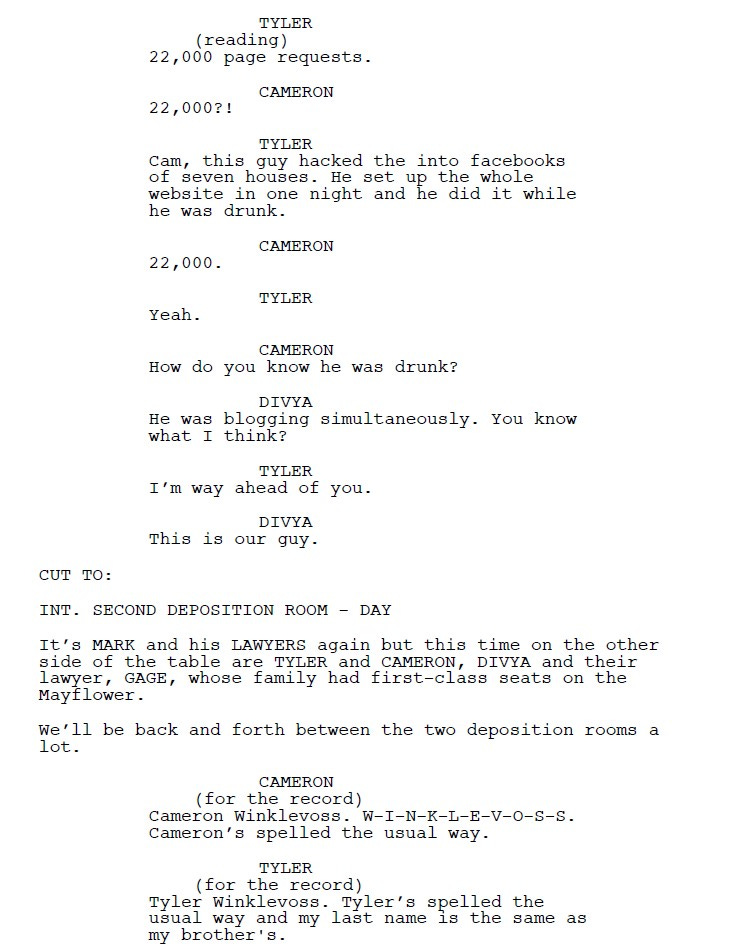

The same goes for the second deposition. The only clue Sorkin gives is that we will moving back and forth between these rooms a lot.

The effect, as we move between the past and present, is similar to that of a tennis volley, zipping back and forth. Coupled with Sorkin’s trademark rat-a-tat dialogue, it moves at almost breakneck speed that leaves you breathless. In fact, the lengthy screenplay is largely due to the amount of dialogue that can run on for pages. Sony Pictures was so hesitant about the possible runtime that director David Fincher would sit Sorkin down and time him reading the script aloud from cover-to-cover. Wouldn’t you know it—despite clocking 163 pages, it only took 120 minutes to finish reading the script. Two hours, in fact, would be the exact running time of the finished film.

I love how rhythm in the dialogue is created through the use of repetition and conflict, almost like a poem stanza.

Sorkin, who came from a background in theater, is spare with description unless required. He will initially frontload the necessary information at the beginning, then keep it to a bare minimum, leaving plenty of room for the director to visualize how the scene will play out.

[INSERT]

In fact, one of the lengthiest scenes without dialogue is the Henley Royal Regatta on page 124-125, presenting the tight race that pits Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss’ team versus the Dutch. But even then, there’s almost an abstractness in the way it unfolds…

Compare that with the way it was filmed. In your head, ask yourself: how would you have done it differently?

Of course, structure and all is great, as is snappy dialogue, but it’s the characters that matter most. The Social Network gives us a great ensemble of them. Mark is presented as an anti-hero who succumbs to a tragic ending in the last couple of pages—he’s the closest to a Shakespearean flawed character; the flaw being his inability to view other people as humans with emotions, and relying on using technology to create his version of what a social experience should be.

There’s Eduardo, too sweet and good-natured to survive Silicon Valley’s ruthless environment; although it’s droll to see that he was ahead of his time in insisting that advertising would be Facebook’s lifeblood, something Mark was vehemently opposed to.

There’s Sean Parker, who embodies everything about Silicon Valley’s culture of thumbing their nose at convention, and has a rivalry with Eduardo.

There’s Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, for whom you can’t help but feel bad for being ripped off on what did turn out to be a billion-dollar idea; although given that they come from money, I suspect that they will survive. I feel more for Divya Narendra.

There’s also another smaller but important character: Marilyn Delpy. She’s a junior associate on Mark’s legal team who serves as our audience surrogate at certain moments as well as a kind of angel-on-the-shoulder figure who explains to Mark what will happen, and why; in the script’s closing moments, it is Marilyn who delivers the last line of dialogue that encapsulates what makes Mark a tragic figure.

We also need to talk about the opening scene. Running at nine pages, it rivals the farmhouse scene in Inglourious Basterds for how to start your screenplay memorably. The setup is simple: Mark is on a date with Erica Albright, but he can’t stop talking about himself and his obsession with getting into a finals club. Within these nine pages, though, Sorkin lays out everything you can expect out of The Social Network: the tone and style; Mark’s character (not great at being a human); his goals (getting into a finals club and attaining status in the eyes of people) and obstacles (he is unable to get the attention of the clubs); the theme (the price of ambition) and Mark’s character arc (he will get what he wants and reach the top but he will be alone and friendless at the end). Above all, it provides the impetus that will kick off the chain of events that ultimately will lead to the invention of Facebook. If you want to know how to write a memorable opening scene, read this opening scene. It is poetic, powerful, and simply gob smacking in the way it pulls it off.

(Note: Sometimes, the best lines can come from real life. For instance, Marilyn’s line about “creation myths” was lifted verbatim from an email by Elliot Schrage, the Head of Global Communications at Facebook at the time the script was written.)

Was Erica Albright real? The name is made up, but the blog posts in which Mark gets drunk, makes inappropriate comments in public about her, and then outlines his plans to create FaceMash, the controversial site, is taken nearly word-for-word from the real Mark Zuckerburg’s blog. There was a girl known only as ‘Jessica A’ who served as the inspiration for Erica. But this character is pivotal despite appearing in only two-to-three scenes. In her second encounter with Mark at a club, Erica delivers a scorching takedown where she derides Mark—and basically nearly every tech bro— that still rings true over a decade later.

The Social Network began life when Sorkin received a 14-page proposal of Ben Mezrich’s The Accidental Billionaires as it was being shopped around Hollywood for a film deal; it was the fastest he’d said yes to such a agreement. He and Mezrich worked on the script and book respectively at the same time but Sorkin didn’t get a look at the book until he was almost finished with the script. One departure was that the book told Eduardo’s story mostly, while Sorkin drew from multiple sources and any available transcripts of testimonies, especially the legal documents, to construct his version. At first, he struggled to write a character that sounded like a 19-year-old, until he gave up and just wrote the dialogue as he normally would. The biggest question that plagued him was how to turn a movie about Facebook into something exciting; for Sorkin, it was the cost of the journey than enshrining what he calls the ‘eureka’ moment in other biopics. It paid off: He earned his first nomination for—and won— the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay1, as well as the Golden Globe Award, the BAFTA Award and the Writers Guild of America Award in the same category.

Sorkin’s penchant for crafting scenes in which the tension builds and reaches the climax is on brilliant display here. My favorite is the one where Eduardo realizes what Mark had done, and confronts him; cutting between the deposition room to the day of the event, especially as it makes Mark look really bad.

Although it takes dramatic license like any biopic, there is a lot of relevance and even foresight about Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg. The Social Network seems to foresee the dangers of the site especially with someone like Mark at the controls; mind you, this was at a time when America was extremely enamored with Silicon Valley and the youngest billionaire ever.

The Social Network screenplay is fabulous. I’m not the only one who thinks so; it’s a favorite of filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, while Quentin Tarantino has publicly acknowledged the film to be one of the greatest of the 2010s. Every time I read it, I always ask, How did they get away with writing a screenplay like The Social Network? I don’t know if I’ve found the answer or even gotten close to it, but I will continue to keep revisiting the script for many years to come.

“It struck me as a great big classic story,” says Aaron Sorkin, “and those classic elements were being applied to something incredibly contemporary. All these themes of friendship and loyalty, class, jealousy, betrayal- all those kinds of things were being written about 4000 years ago.”

Notes:

Buffery, Adam | From Facebook to ‘Fuck-You Flip-Flops’: How Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher Made ‘The Social Network’ a Fiery Word-Off (Cinephilia Beyond)

Harris, Mark (September 17, 2010) | Inventing Facebook (New York Magazine)

THR Staff (February 4, 2011) | Aaron Sorkin, ‘The Social Network’ (The Hollywood Reporter)

Grosz, Christy (December 7, 2010) | Anatomy of a Contender: ‘The Social Network’ (The Hollywood Reporter)

Bereznak, Alyssa (September 22, 2020) | Ten Years Later, Mark Zuckerberg Is Still Trying to Overcome ‘The Social Network’ (The Ringer)

Hoffman, Claire (September 15, 2010) | The Battle For Facebook (Rolling Stone)

Other contenders in both Best Original and Adapted Screenplay categories that year selected for the WGA 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century List: Toy Story 3, and Winter’s Bone (Adapted); The King’s Speech, and Inception (Original).