Toy Story 3 (2010) Script Review | #44 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A heart-warming sequel that riffs on THE GREAT ESCAPE proves there's still plenty of life in Pixar's first franchise.

Logline: As a grown-up Andy prepares to leave for college, Woody, Buzz Lightyear, Jessie, and the gang accidentally wind up in a nefarious day-care center. Working together, the toys must find a way to escape and return home to Andy before his departure.

Written by: Michael Arndt

Story by: John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Lee Unkrich

Pages: 130

“When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me.” – 1 Corinthians 13:11

Toy Story 3 takes the above saying and turns it into a feature-length story about learning to accept the change that comes with time and move on. The franchise has admirably succeeded in exploring abandonment issues from different angles. The third instalment meditates on what happens to the toys when children stop playing with them, and how they cope, wrapped up in a prison break movie in the vein of The Great Escape. It’s got plenty of laughs and, unsurprisingly for a Pixar story, plenty of emotional punches.

The screenplay begins and ends on the image of a blue sky; and begins and ends with Andy, the human protagonist of the series, playing with his toys.

The only difference is that in between, Andy has grown into a young adult heading off to college. What does that mean for Woody, Buzz Lightyear, and Jessie—as well as Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head, Rex, Slinky the Dog, and Andy’s other toys? A glimpse was offered back in Toy Story 2 when Jessie’s backstory was revealed— toys get abandoned when their owners grow up. Sure enough, Woody and the gang have been put away in storage for years. A failed attempt to get Andy to play with them outlines the emotional stakes: toys depend on humans for play; to be played with is their purpose. Without it, they are lost.

After opening with one of Andy’s fantastical adventures that foreshadows the climax and a montage of Andy growing up, the story jumps 10 years by page 8.

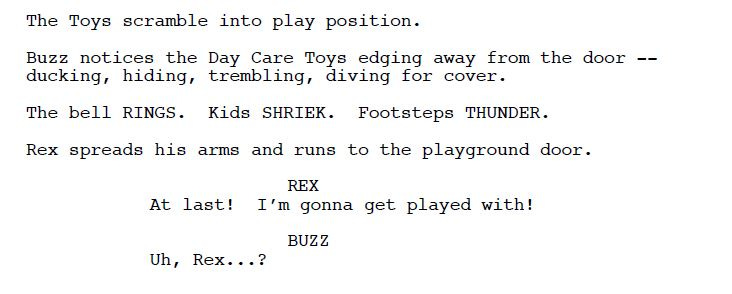

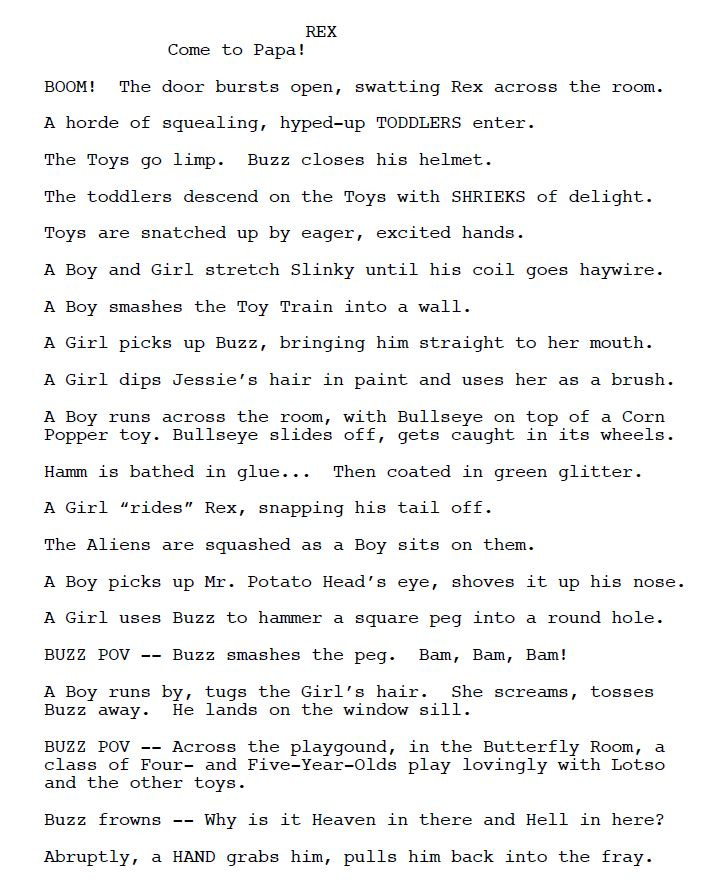

Andy decides to take Woody to college and put the rest of the toys in storage. But instead of ending up in the attic as planned, a series of misunderstandings lead to the toys mistakenly believing that Andy was discarding them. The toys, Woody in tow, wind up at Sunnyside Day Care Center. Run by a cuddly pink bear named Lotso and aided by a giant baby doll named Big Baby, the Day Care Center sounds like paradise to the toys. They will be played with all the time instead of gathering dust in a box. Woody isn’t sold, though, and leaves the toys to return to Andy. However, he ends up instead in the care of a sweet kid named Bonnie and discovers a dark secret: Sunnyside Day Care Center is a prison for toys, and Lotso holds sway over all. Although most of the children at the Center are gentle, others are not. The new batch of toys are assigned—forebodingly—to these rambunctious children in a sequence that teeters between hilarity and horror.

And when Buzz goes to negotiate with Lotso, the plushy bear’s true colors come out: He turns Buzz by resetting him to believe he is a space ranger, and imprisons Andy’s toys. Now it’s up to Woody to break in and break them out.

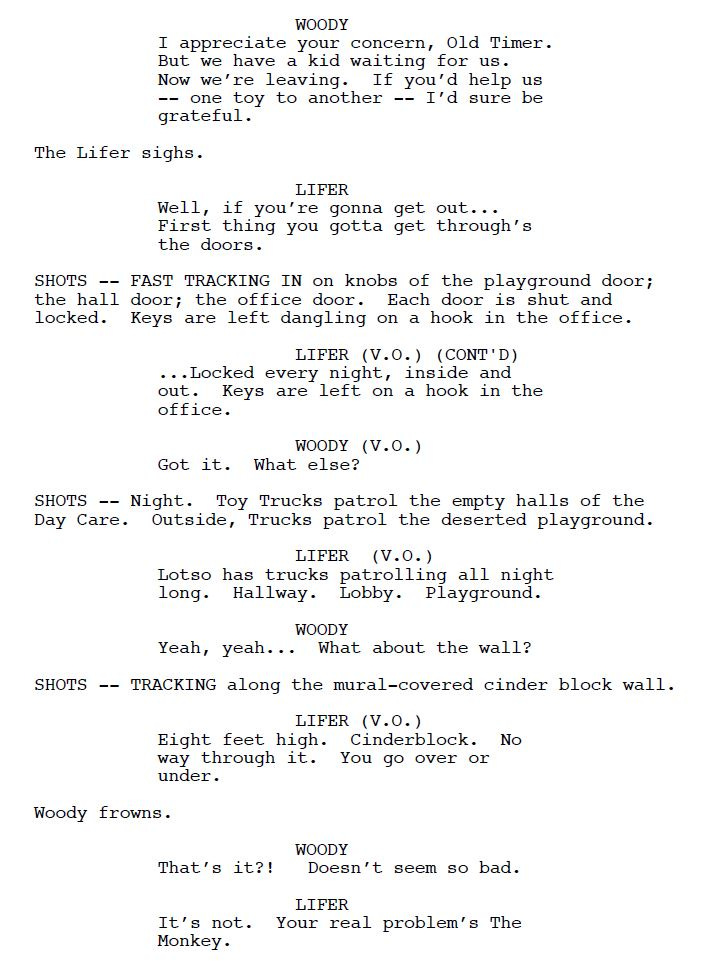

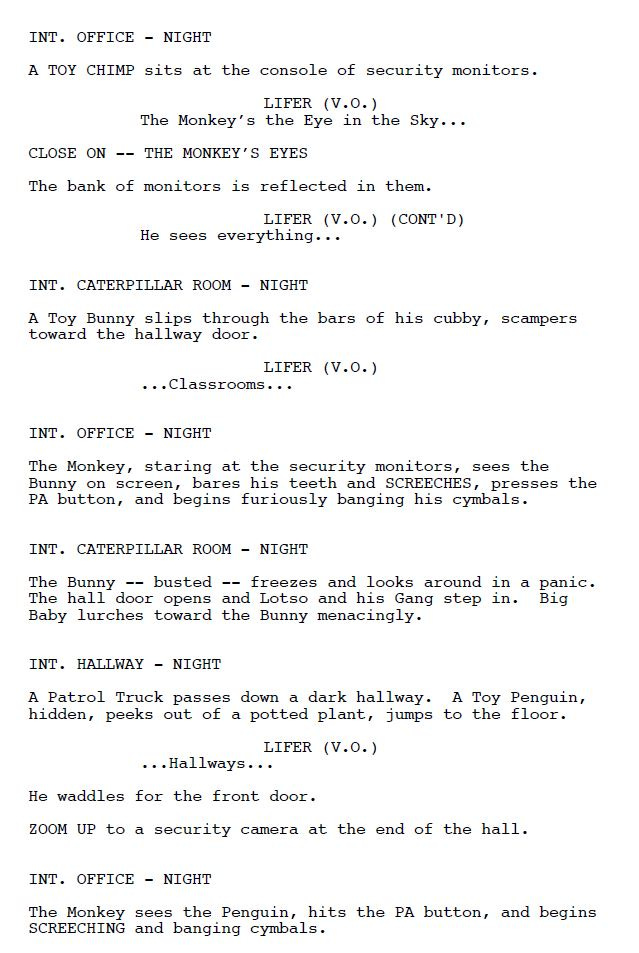

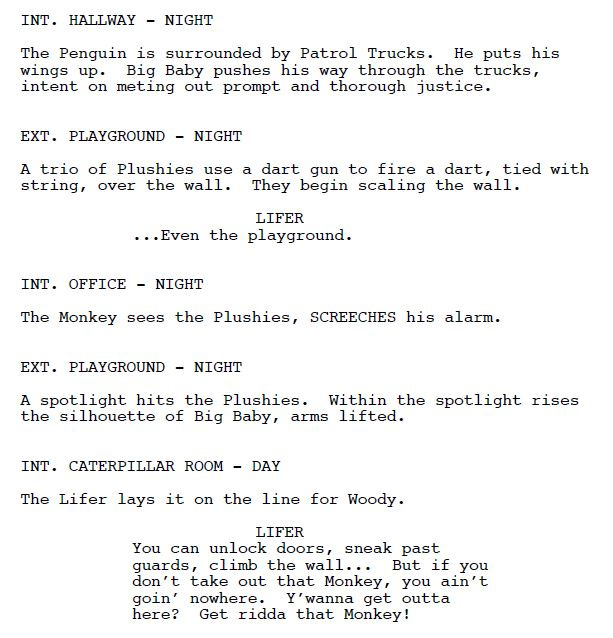

Although it borrows from heist flicks for the breaking-in sequences and from escape movies for the getting out parts, nothing about it feels like a parody. Here, Woody gets a detailed escape plan from one of the Lifer toys, setting up precisely what has to be done and the obstacles they will face.

The script takes time to introduce new characters and even give other supporting characters their own arcs. For instance, there’s a sub-plot in which Barbie meets Ken, where the former is an intelligent character and the latter must choose between Barbie and his allegiance to Lotso. There’s Bonnie, who becomes the new owner of Andy’s toys; and even the Potato Heads have more to do this time around. A good script needs a good crew of supporting characters.

But it also needs a formidable antagonist and Lotso delivers. This Stalin-esque figure comes with a tragic backstory that gives the toy bear depth and flaws. The backstory is that Lotso, Big Baby, and a third toy (Chuckles the toy clown) were once accidentally left behind; after a long trek, Lotso discovered that his owner, Daisy, had replaced him. Snapping, he convinced Big Baby that all of them had been replaced, and eventually took over Sunnyside.

Big Baby is the linchpin to overthrowing Lotso. For Woody to realistically defeat Lotso, he has to convince his supporters to turn on him. Mostly, though, he needs to convince Big Baby that Lotso lied to him. The tactic not only feels realistic, but feels earned.

One thing to focus on is how the script gets economical with the emotional beats. Compare how the climactic (and traumatic) scene of the toys in the trash compactor is written versus how it plays out. One line for each beat. Simple. Almost like a haiku. Yet powerful.

How this moment was filmed:

Something that is missing from both Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3 is more time spent with Woody and Buzz. This pairing was the beating heart of the first Toy Story and while their friendship has never been in doubt since, it’s a shame that the sequels don’t devote more time to it.

Toy Story 3 was the first time a non-Pixar writer was hired to write the screenplay. Lee Unkrich roped in Michael Arndt in the same week that Little Miss Sunshine (#21 on the WGA’s 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century list) broke out at the Sundance Film Festival. Arndt moved to Pixar headquarters to write the script, and brings a wonderful flair and humanity to the writing.

Although the team of the first film had been kicking around ideas for sequels for years, it took a long time for anything to materialize. But in March 2006, John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter, and Bob Peterson, along with Jeff Pidgeon and producer Darla K. Anderson, went on a two-day retreat to the Poet’s Loft in California. It was here in this very cabin that the team broke the story for the first Toy Story a decade earlier. But 20 minutes into the first day, the team abandoned the idea for a sequel they’d been discussing for years! Stumped, the team spent the rest of the day rewatching Toy Story and Toy Story 2.

On the second day, things began to look promising. They tossed new ideas around until they settled on the bones of what ended up in the final screenplay. Stanton put them down into a treatment; the treatment was broken down into 25 sequences; each sequence would undergo 10 drafts or more (Arndt says one sequence even went through 60 drafts!). Rough reels were made to test these sequences, refining them until everyone was happy with the end result.

It’s hard to overstate how successful the results turned out. Apart from making a billion dollars at the box-office, earning much more in merchandise, and winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, Toy Story 3 became the second Pixar feature and third animated feature to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture. For his screenplay, Arndt became the first writer to receive Academy Award nominations for his first and second scripts, and in different categories (for Toy Story 3, it was Best Adapted Screenplay). That’s because the script is tightly constructed and is powerful in its simple examination of the fate of the toys left behind when children no longer play with them. We grew up with Andy. But like for Andy, toys like Woody, Buzz, and Jessie will remain a part of us no matter how old we grow.

Notes:

McLean, Thomas J. (January 11, 2011) | The Making of “Toy Story 3” (The Hollywood Reporter)