The King's Speech (2010) Script Review | #73 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

The King's Speech turns a private chapter in the life of King George VI into a moving and unfussy drama.

Logline: After his brother abdicates, George ('Bertie') reluctantly assumes the throne as King George VI. Plagued by a dreaded stutter and considered unfit to be king, Bertie engages the help of an unorthodox speech therapist named Lionel Logue. Through a set of unexpected techniques, and as a result of an unlikely friendship, Bertie is able to find his voice and boldly lead the country into war.

Written by: David Seidler

Pages: 90

I feel bad for The King’s Speech. Even though it was nominated for 12 Oscars at the 83rd Academy Awards and won 4, including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay, it is mostly remembered as an ‘usurper’ that stole the Oscars from the better film that year, which happened to be The Social Network (the screenplay for which is ranked No. 3 on this list). That’s a shame because if you look past that— and the fact that it’s got all the allure of a once-beloved Hollywood relic (you know: period piece set in Britain during World War 2 and based on a true story)— you’ll find that David Seidler’s script has a charm of its own. It’s solid, dependable, and unfussy, yet stirring and moving at its most powerful moments, when it remembers that its subject, beneath the regal airs and the crown, was still just a man desperate to overcome his stammer and not embarrass himself.

Although the protagonist is the future King George VI, in the script, he’s only referred to as Bertie. When his brother decides to abdicate in favor of living with a divorced American woman, Bertie is forced to take the throne; which means he has to address his subjects through public speeches. And Bertie is terrified of public speaking because it brings out his stammer. When the unorthodox methods of an unconventional speech therapist, the Australian Lionel Logue, shows promise, Bertie slowly comes into his own and must rally England as the Empire hurtles towards the unstoppable prospect of World War II.

A simple premise, with personal stakes entwined with big stakes, and heaps of amusing dialogue. The King’s Speech runs for a brisk 90 pages, somehow compressing over a decade (1925-1939) into three Acts that works out as follows:

Act 1

Setup (pages 1-14)

Bertie messes up the Wembley speech due to his stammer, prompting a failed search for speech therapists to help him, until Elizabeth finds Lionel Logue

Inciting Incident (pages 15-25)

Elizabeth convinces Bertie to see Logue who bets that the Duke of York can read without stammering but Bertie feels his case is hopeless and leaves with a recording

Plot Point 1 (pages 26-30)

But after a painful encounter with his father, King George V, Bertie listens to the recording and he and Elizabeth are stunned to hear him reciting Shakespeare without a stammer, convincing the Duke of York that Logue may be able to help him after all

Act 2

Rising Action (pages 31-38)

Logue begins his sessions with Bertie, David returns to England before King George V dies, forcing him to ascend the throne

Midpoint (pages 39-53)

Bertie discloses some of the painful memories to Logue that contributed to his stammer, the Yorks try and fail to adjust to David and Wallis, and Bertie is aghast that David plans to marry Wallis which is against the constitution

Plot Point 2 (pages 54-58)

Bertie, feeling devastated by David causing his stammer to return in full flow, confides in Logue about why he’s upset but when Logue tries to offer support to Bertie, the latter is shocked and breaks things off with Logue

Act 2 Out (pages 59-79)

As Bertie is made king in David’s abdication, the therapist and royal patch up their differences so that Bertie can speak at the Coronation but the storm clouds of war hang over England

Act 3

Build Up (pages 80-84)

Although the Coronation goes well, Prime Minister Baldwin hands in his resignation, which leads to Chamberlain, which leads to Churchill

Climax (pages 85-87)

3 September 1939- Bertie summons Logue to help him deliver the titular King’s Speech that will be broadcast live to the Nation, Empire and Armed Forces

Finale (pages 88-90)

The speech is a success, Bertie shows his gratitude to Logue

The A-plot (or main plot) focuses on Bertie’s efforts to overcome his stammer; the B-plot concerns the political events unfolding within the palace, as well as Logue’s home life; thus, devoting time to both men outside of the therapy session that fleshes them out.

For Seidler, The King’s Speech was a passion project that took years to reach the screen. Seidler, like King George VI, had a stammer. Seidler’s research into the king started during the 1970s and 1980s (when the Cold War was still raging!), but he held off on publishing anything on the subject at the request of the Queen Mother (Bertie’s wife, Elizabeth) until she died— in 2002! Can you imagine shelving your passion project for over a decade??

However, an early version of Seidler’s screenplay was not well received by his writing partner and then-wife, Jacquelin Feather, who felt that Seidler had been “too seduced by the cinematic technique.” It was her suggestion that led to Seidler reworking it as a play, keeping the focus on Bertie and Logue. By a fortuitous series of events, he was granted access to the real Logue’s notebooks— nine weeks before filming began! Armed with new information, he went back and reworked the script, lifting bits of dialogue directly from the notebooks, such as this part about stammering on the letter ‘W’:

In all scripts based on true stories or true events, a certain amount of creative license is always taken, and The King’s Speech is no exception. About 70% of it is historically accurate, but there is a distinctly pro-monarchy vibe in the screenplay, notably in its unflattering portrayal of Wallis Sampson.

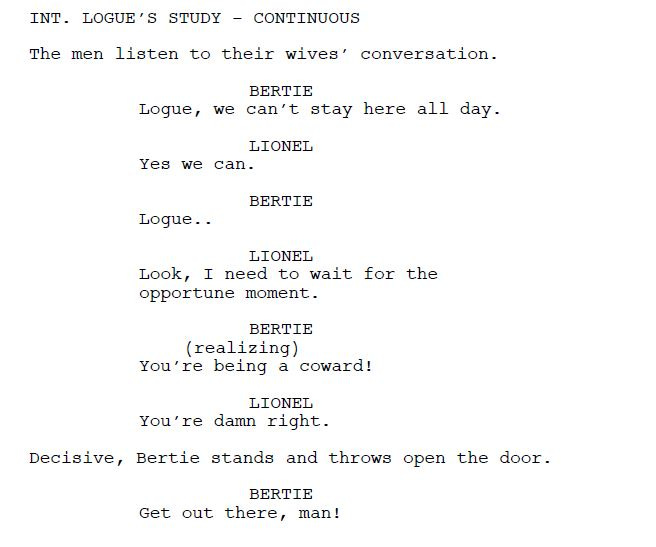

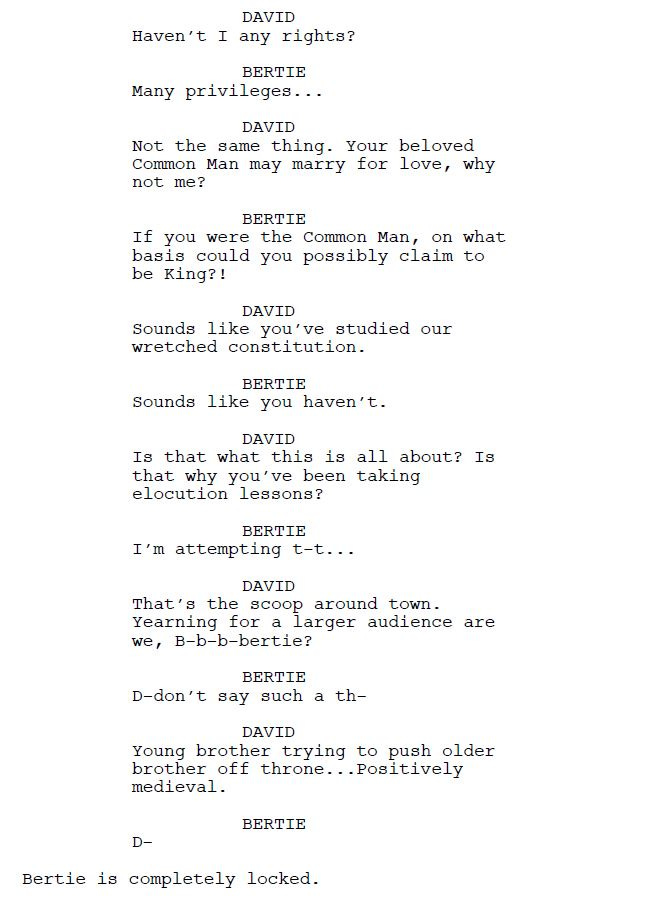

But it works because it follows the laws of drama, and because it’s also quite funny. You wouldn’t expect it to be so, but it is. Logue, outspoken and unorthodox; Bertie, reserved and the epitome of constrained. The two make for great sparring partners, mining their interactions for every laugh he can get out of it. But in their friendship, too, he finds moments of humor that help to humanize all the characters, such as the droll scene where Logue’s wife walks into the kitchen and finds the Queen- and a horrified Logue hides to avoid his wife until Bertie shoves him to go deal with it:

Seidler’s writing is— to put it simply— lovely. His theater background makes this no surprise but look at the way he sets up the BBC Reader’s prep routine in the opening pages:

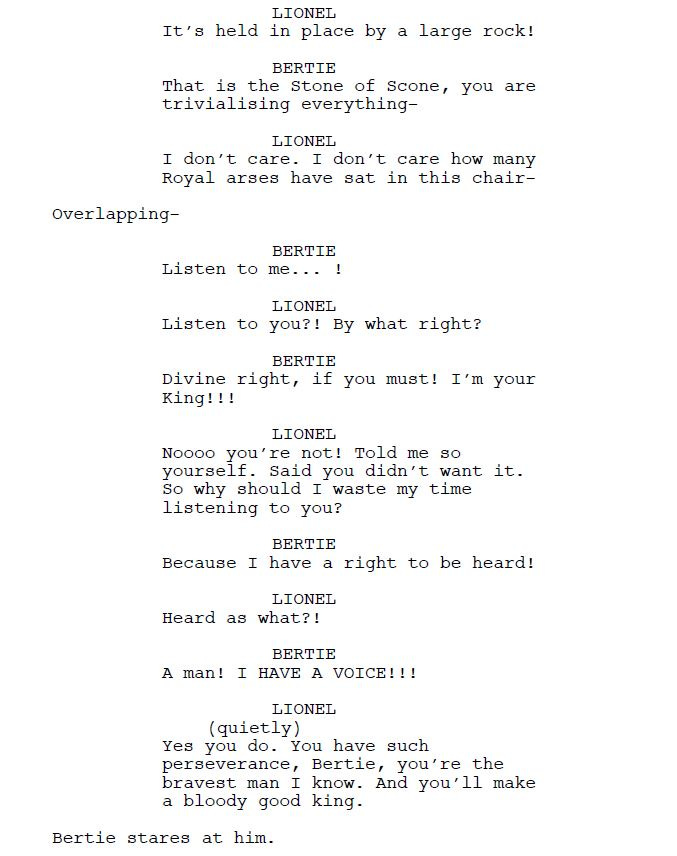

And his dialogue is unfussy and eloquent, turning exchanges into volleys tossed back and forth between characters with all the energy of a tennis match, using reliable techniques of repetition and, yes, plain old-fashioned conflict.

The King’s Speech also uses a technique of ‘full circle’— that is, it opens and ends in a similar fashion to highlight how far Bertie has come on his journey; it starts in 1925 with Bertie failing the Wembley address and concludes with Bertie, as the king, rallying his country in 1939 to go to war.

How does Seidler write a stutter in a screenplay? Because if every line of dialogue has a stammer, it would make for difficult reading if dialogue was consistently w-w-written l-l-like t-this. What Seidler does is simple: he writes Bertie’s very first lines of dialogue with the stutter indicated, then makes a comment within square brackets that is addressed directly to the reader and the actor.

The stutter then only occasionally shows up; else, it reads normally.

As much as I am in the camp of people who think The Social Network was the best picture of 2010, it doesn’t mean that David Seidler’s script should be cast aside. It is quick, it is trim, and it moves fast. The passion and empathy for his subject is evident in every line and scene that Seidler has written. Sometimes, passion projects can take a long time to see the light. But if you believe in it like Seidler did, I think that you’ll find a way to get it made, and people will respond to it. And hey, if it is based on a true story and just happens to involve the British monarchy, your odds might just shoot up in your favor! For The Crown has made it pretty apparent that the public very much has an appetite for all stories concerning the Royal Family of England.

Note: David Seidler died aged 86 on March 16, 2024.