Inglourious Basterds (2009) Script Review | #8 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Quentin Tarantino does his version of the men-on-a-mission genre and takes a giant swing at World War 2. What glorious fun!

Logline: In Nazi-occupied France during World War 2, a group of Jewish-American soldiers known as “The Basterds” spread fear throughout the Third Reich by scalping and brutally killing Nazis. The paths of the Basterds, led by Lt. Aldo Raine, are intertwined with a French-Jewish teenage girl who runs a movie theater in Paris, as both sides work independently to wipe out the High Command of the Third Reich.

Written by: Quentin Tarantino

Pages: 164

In Inglourious Basterds1, Quentin Tarantino puts his own spin on the men-on-a-desperate-mission story and combines it with a tale of revenge, and ends up creating something else altogether. It’s like The Dirty Dozen, The Guns of Navarone, and Tarantino’s own Kill Bill movies tossed together into a fascinating and bloody entertaining World War II yarn, one that has the filmmaker’s unique fingerprints all over it.

A group of Jewish-American soldiers called ‘the Basterds’ are dropped into Nazi-occupied France to brutally kill and scalp German soldiers. Led by Lt. Aldo Raine, they move through the country and become a source of terror to the Nazis. In Paris, a Jewish teenage girl who survived the massacre of her family ends up in the ownership of a small cinema; when the Nazis select her theater to host the premiere of Goebbels’ latest film, Shosanna finds herself in a unique position to take out the entire High Command of the Third Reich attending the event. But as her path unknowingly crosses that of the Basterds who have the same objective, both sides have to reckon with a fearsome foe capable of derailing their plan: the charming, cunning, and ruthless Nazi, Colonel Hans Landa.

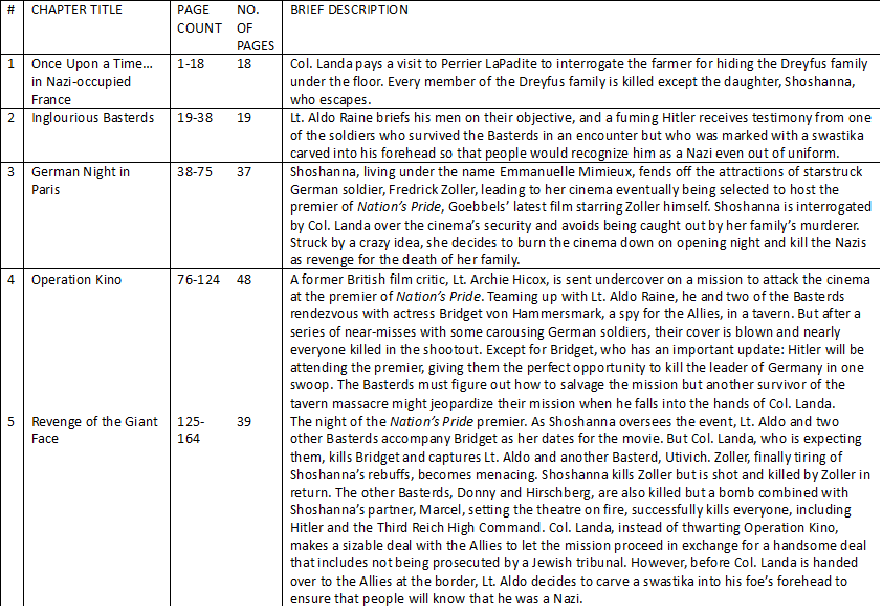

As he did with Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction, Tarantino takes a novelist’s approach by dividing his script into five chapters, each of varying lengths:

At a glance, you’ll notice that the first two chapters are quite short—37 pages altogether— and can be said to form the entirety of Act 1. Meanwhile, Chapters 3 and 4 would be the base of Act 2, totaling 85 pages; and Chapter 5 would be Act 3, clocking 39 pages. This would be the closest to Tarantino following a traditional three-Act structure, yet even then, it still strives to be its own thing. To understand how this works, it helps to know how this story came to be.

Tarantino had been working on the initial Inglourious Basterds screenplay on and off since 1999; but the story soon morphed into something too big and unwieldy. He put it aside to focus on making Kill Bill, but when he picked it up again, he was still at a loss on how to make it work. A six-month research period didn’t do offer much help, either. If anything, it almost “paralyzed [his] writing for a while.” Debating between making a World War II documentary or a 12-hour mini-series, he decided to take another stab at the story sometime around 2008. Only this time, some drastic choices were made. Tarantino took the entire story out, leaving only the first two chapters— the farmhouse and the Basterds’ introduction—and departed from the conventions of a war movie. Instead of following it with the obligatory ‘mission briefing’ that happens in Chapter 4, he wove in Shosanna’s story for a good chunk of Act 2, before returning to the story of the Basterds via the introduction of Lt. Hicox. When you study the structure carefully, you’ll notice that the Basterds only pop up in the beginning and towards the end!

At first glance, such a move should not work. But it does! Imagine, for instance, if The Avengers began with all the members of the team boarding the Helicarrier, only then to cut away to a storyline set in New York that would eventually connect to the Battle of New York in Act 3, during which time the Avengers would reappear in the story. Or imagine if in Saving Private Ryan, Captain Miller and his team embark on their mission through the countryside of France, only for the film to cut to Private Ryan in the town before whatever is left of Miller’s unit arrives to find him. That, more or less, is what happens here. Reading Inglourious Basterds is to marvel at Tarantino’s audacity for thumbing his nose at convention and get away with defying the rules.

Although it runs up to 164 pages, there’s three things worth mentioning. The first thing is that a lot of pages are taken up with reams of dialogue, as Tarantino is famous for his gift of gab; accordingly, scenes that run on would actually take less screentime than the number of pages would suggest.

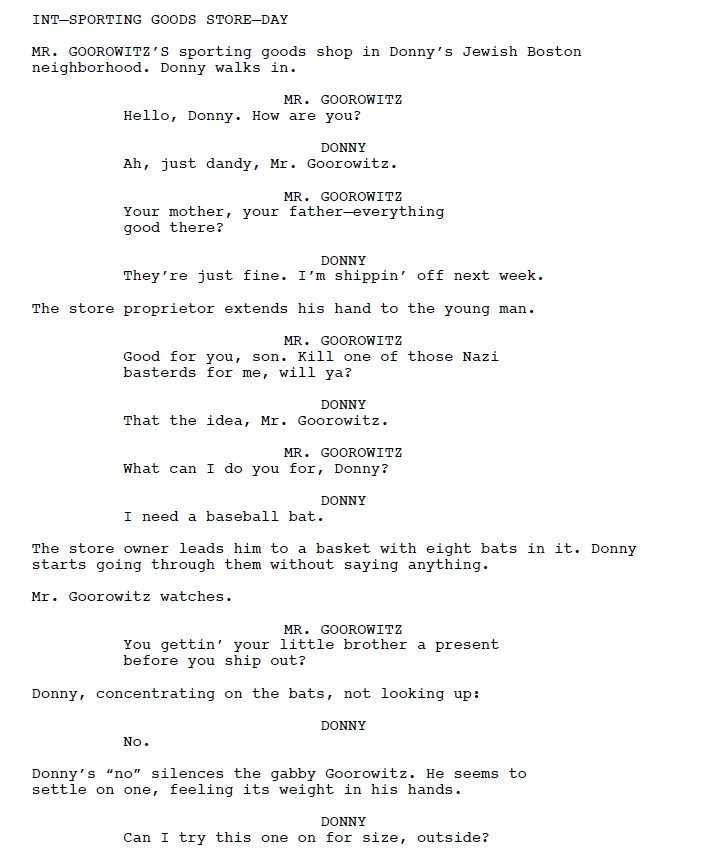

The second thing is that the Inglourious Basterds screenplay contains a lot of scenes and information that was either not shot or was omitted in the theatrical version of the film. This includes scenes that flesh out Donny’s pre-war past as a barber and how he got the baseball bat that earned him the nickname, ‘the Bear Jew,’ from the Germans.

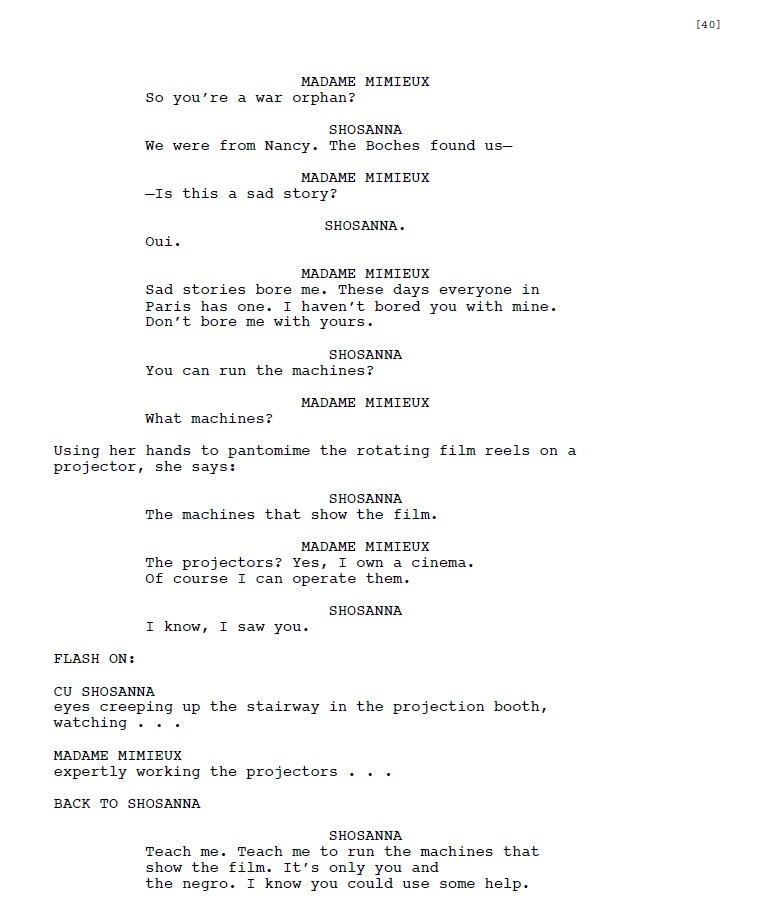

It also includes backstory as to how Shosanna came to Paris and into the ownership of the cinema, run by Madame Mimieux…

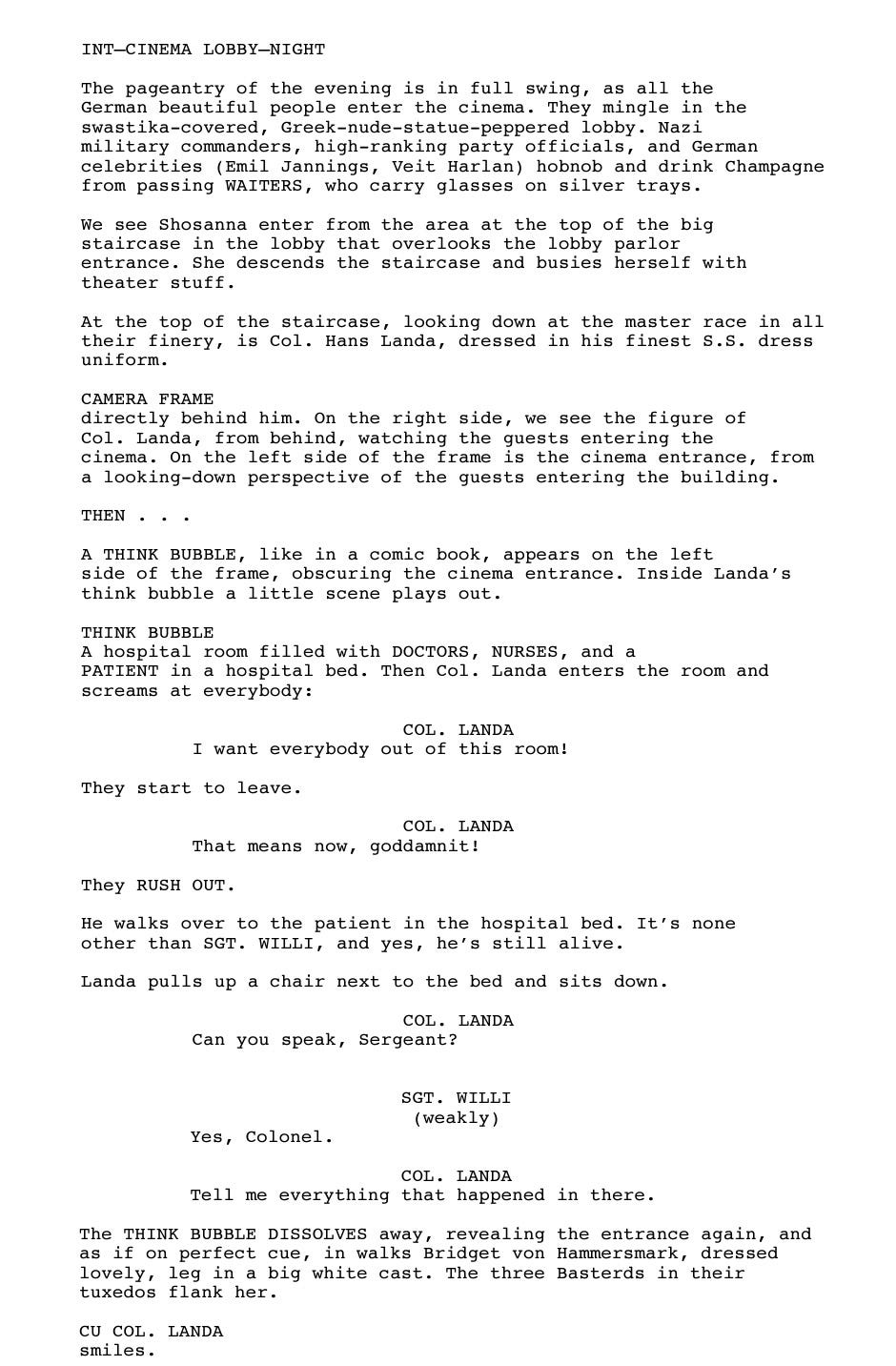

Perhaps more crucially, how Colonel Landa came to learn about Bridget von Hammersmark being a double agent and being prepared for the Basterds in Chapter 5— one of the soldiers, Willie, survived.

Another scene that got axed was a brief moment when Shosanna crosses paths with some of the Basterds, the only time in the script that they do, on pages 132-134.

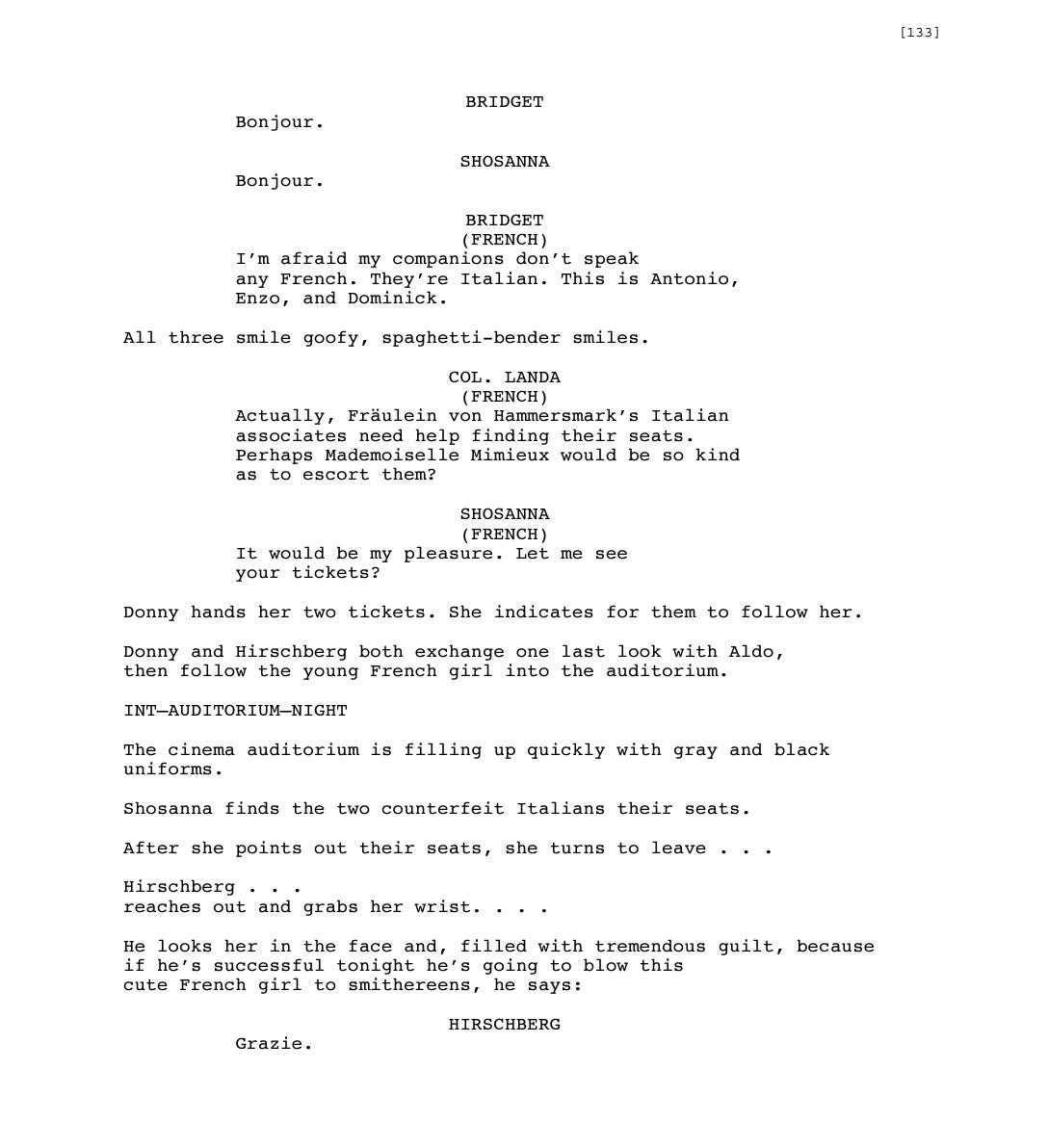

Yet other scenes that get omitted include moments between Marcel and Shosanna alone together…

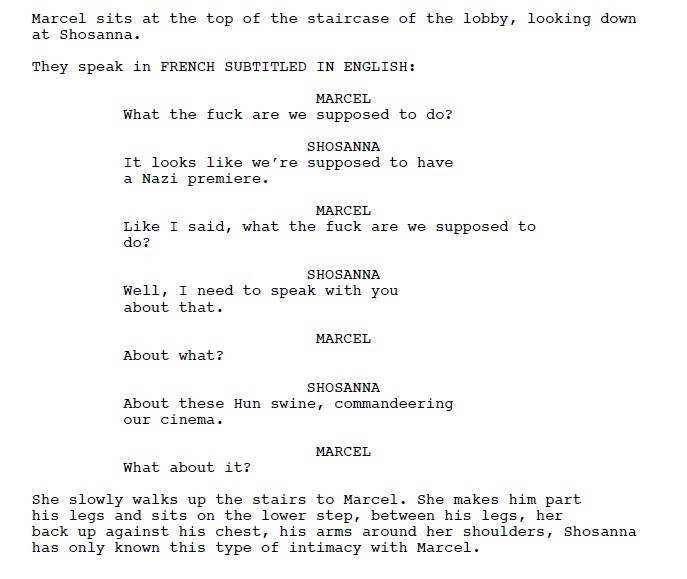

And a little backstory about Fredrick Zoller that humanizes him almost. ALMOST.

Although these scenes flesh out and add to the characters, they don’t necessarily add too much overall to the main story. While I wish the little moments between Marcel and Shosanna were kept— the sweet and tenderer moments in an otherwise violent script— it’s important to know what to take out in the service of pacing and momentum; for they do slow it down when compared to the finished film.

The third thing is that Act 3—or Chapter 5—was significantly overhauled for the film. In the script, Donny, Hirschberg, and Shosanna’s fates play out differently. Donny is killed in a shootout by one of the German soldiers marked by the Basterds in Chapter 2…

… while Hirschberg is essentially a kamikaze soldier when his ankle-bomb goes off in the midst of the swarming crowd trying to get out…

… and Shosanna’s death includes a moment where she has to change the reel before she succumbs to the wounds received from Zoller’s shooting (which is much more violent in the script).

What happened is that this was how the ending was supposed to play out when Inglourious Basterds went into production. But according to the First Assistant Director on the film, William Paul Clark, Tarantino reworked the ending over the Christmas holidays in 2008 when they took a break, cobbling an outline with little snippets of dialogue. “He wrote this out by hand and handed me a stack of yellow ruled paper,” Clark remembers. It was his job to organize the logistics.

Thus, Donny, Hirschberg, and Shosanna’s fates would play out differently—Donny isn’t killed separately; instead, he and Hirschberg place the bombs near their seats, and proceed to machine-gun Hitler and his top-ranking officials as the cinema goes up in flames and the bombs finish the job. Likewise, Shosanna’s death is faster, and there’s no bit about her needing to change reels before she breathes her last. Needless to say, this new version works better.

A similar situation occurred with Tarantino’s follow-up feature, Django Unchained (#74 on the WGA List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century), where the ending of the screenplay diverged from what was filmed eventually. When Tarantino writes, he doesn’t have an outline; nor does he know how it will end. Instead, he knows that some scenes will get him to where he wants the story to go. I suppose being Tarantino, he can get away with it, but for those starting out, having an outline is always helpful. There’s an interesting anecdote about how Quentin Tarantino writes a screenplay. Apart from not using an outline (because he wants the characters to direct the action), Tarantino also writes the first drafts of his scripts in longhand.

“I’ll do a little like, ‘This thing goes into this thing goes into this thing,’ maybe for, like, the first half or something, just to get a sense of how I’m starting, and I have an idea where I’m going to go with it,” he says. “I’m trying to get to that place where now the characters are telling me [the story] and the characters are exciting me. … It’s the characters who really write the piece.”

When he’s done and it’s time to rewrite, edit, and put it together in a more professional-looking format, Tarantino eschews using modern computers or modern screenplay software. Instead, he types up the script with one finger on a Smith Corona word processor. You may ask, why a Smith Corona word processor—and dear God, why one finger? These are not accidental choices, but crucial limitations to bringing out the best in his creativity. The limited memory on the Smith Corona means he has to print every page before he can continue, allowing him to look and assess it page by page. Using one finger to type out a scene acts as a filter—if a scene does not pass muster, out it goes, because typing with one finger is EXHAUSTING. The man isn’t going to waste his time on a shitty scene when his energy is limited. It might sound extreme but using limitations like a word processor with small memory capacity and typing with only finger can actually forces you to slow down and really think through what you’re writing.

Where the writing is concerned, the man has never been in better form. The introduction—in fact, the very creation—of Col. Hans Landa might be Tarantino’s finest moment. Landa’s arrival at the farmhouse and his subtle interrogation that initially doesn’t seem like an interrogation is an excellent example of how to introduce a character…

… and how to use dialogue to reveal character, and build suspense in your screenplay.

Similarly, Tarantino takes a novelistic approach to his writing, unafraid to use long paragraphs when describing a scene.

Another example:

But the words aren’t meaningless— like any good screenwriter, he is helping to build the image in the reader’s head and set the scene. As for his penchant for dialogue, the moment where Landa initially lets Perrier LaPadite lower his guard before ensnaring the farmer into a confession needs to be read to believe it could work. No frills, no fuss.

A caveat: While Tarantino’s dialogue can be delightful, it is sometimes taken to excessive lengths and actually robs the script of its impact, undercutting the tension, even. For instance, take the scene on page 94, where Bridget von Hammersmark reveals that the Führer will be at the premier.

In the film, this piece of information is saved until Lt. Aldo interrogates Bridget after things go south in the tavern. Why is this a good move? Because a) it avoids repeating information that we already know, and b) it builds suspense. You are curious to know what is so important for Bridget to say, and when she is thwarted, it keeps the curiosity burning.

On the other hand, it’s a little comforting that even pros like Quentin Tarantino can make mistakes when he’s writing.

One thing I was curious to find out is how he incorporated German, French, and English into the script without resorting to translating the dialogue. There are plenty of scenes in which German and French are spoken; especially if it needs to be interpreted, repeating dialogue can be time-consuming on the page. Plus, what if you don’t know the language? Tarantino solves that without breaking a sweat. Here’s how Inglorious Basterds manages interpretation scenes:

At all other times, it’s implied that English is spoken. Meanwhile, here is how Tarantino handles intercutting scenes to save both page space, as well as time.

When a screenplay is written, a common question asked is: what is it about? What, then, is Inglorious Basterds about? Well, what are any of Tarantino’s scripts really about? Although it’s set during World War II, it’s certainly not a commentary about it. If anything, it’s a fantasy version of World War II, one that cheerfully rewrites history. It’s a fun pulpy adventure that doesn’t necessarily see characters undergoing any emotional changes— neither Shosanna nor the Basterds transform as characters by the end of the script. Inglourious Basterds was nominated for the Academy Award, BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe Award for Best Original Screenplay. Either you’ll find it a riot or you’ll find it an unbearable mess. I, for one, love it.

Notes:

Hemphill, Jim (March 18, 2020) | “We Kept the Third Act in a Safe”: Tarantino’s Assistant Director William Paul Clark on Kill Bill, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Improvisational Logistics (Filmmaker Magazine)

Macauley, Scott (February 7, 2010) | A Night at the Movies: Quentin Tarantino on Inglorious Basterds (Filmmaker Magazine)

Hohenadel, Kristin (May 6, 2009) | ‘Bunch of Guys on a Mission Movie’ (NY Times)

Callaghan, Dylan (October 10, 2003) | Dialogue With Quentin Tarantino (All Business)

Horn, Jordana (August 21, 2009) | Glorious Bastard (Forward)

Kalfrin, Valerie (September 16, 2019) | Timeless Screenwriting Wisdom from Quentin Tarantino (ScreenCraft)

The title Inglourious Basterds is inspired by Enzo G. Castellari’s 1978 Italian film The Inglorious Bastards, but apart from that, there’s no connection to the film.