Spotlight (2015) Script Review | #31 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Powerful in a quiet way, Spotlight is a gripping drama that dramatizes how a team of journalists exposed decades of abuse hidden by the Catholic Church.

Logline: Inspired by true events, the Boston Globe uncover a massive scandal of child abuse and covering-up within the local Catholic Archdiocese, shaking the entire Catholic Church and community to its core.

Written by: Josh Singer & Tom McCarthy

Pages: 139

Scenes: 179

In the words of Kurt Vonnegut: All this happened, more or less. In early 2002, The Boston Globe broke a damning story about the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston covering up decades of priests sexually abusing minors. This is how that story came to be, pulling off a difficult feat: turning investigative journalism into a gripping tale of accountability and power.

It begins with a brief prologue in 1976. A young police officer witnesses the bishop picking up one Father Geoghan from the station instead of being charged for abusing two kids (implied); we see that the Assistant District Attorney of Boston made sure of that. In a few pages, we discover that both the Catholic Church and the legal system are in cahoots to protect the offending priests instead of doing right by the victims.

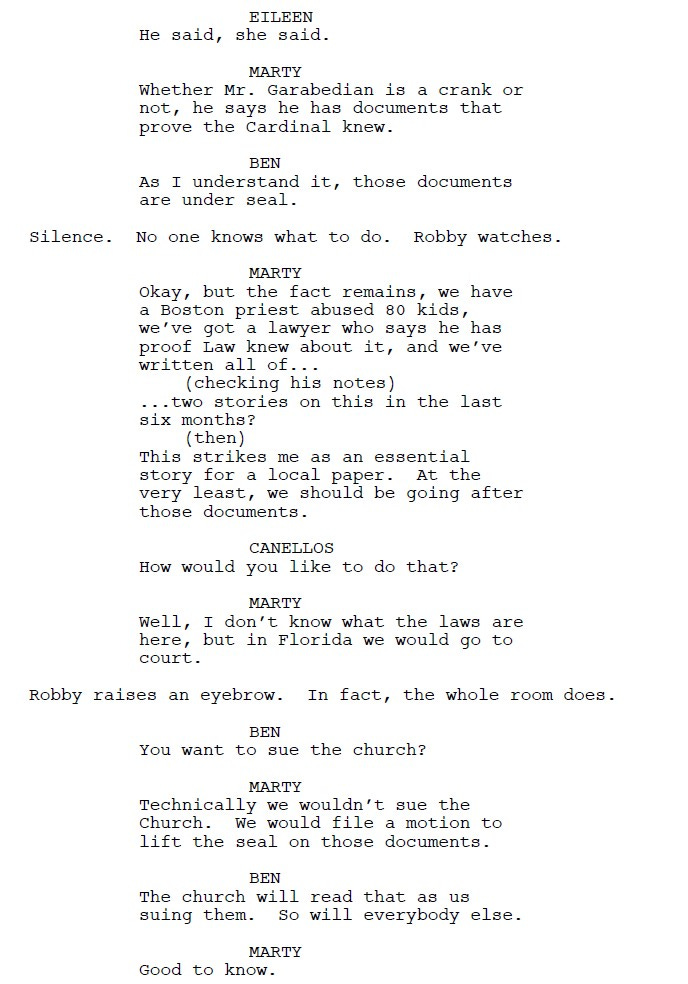

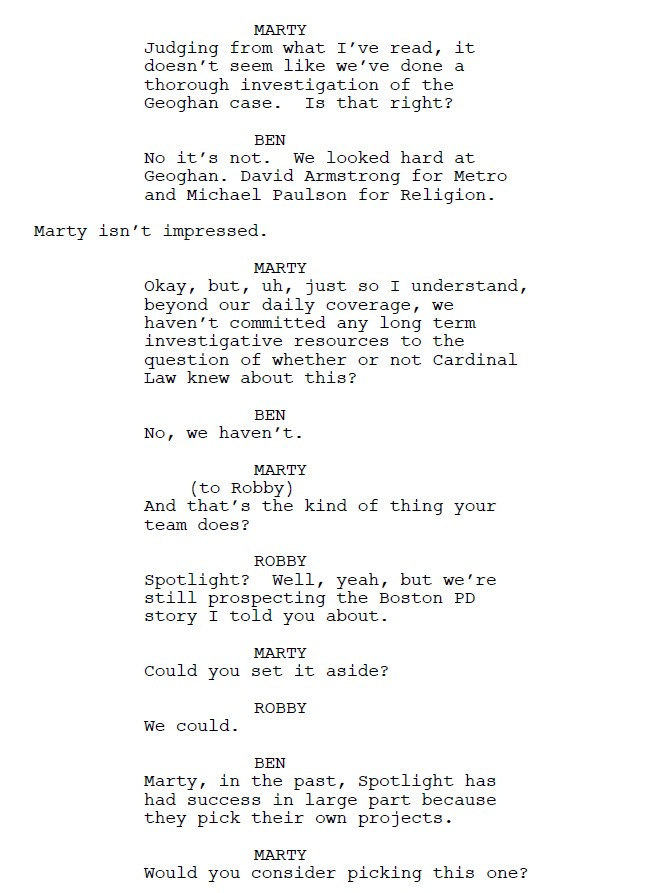

In July 2001, The Boston Globe bids farewell to its longtime editor and warily welcomes the replacement: Marty Baron. Quiet, bookish, a mind of steel behind an unassuming façade, the Jewish Marty is a fish-out-of-water in the predominantly Catholic Boston. But the arrival of outsiders always has the power to shake things up. In an understated yet quietly gripping scene, Marty wants the Globe dig deeper into a story about a lawyer claiming he has proof that Cardinal Law knew about Father Geoghan’s crimes and did nothing.

Shortly after, he assigns the project to the Spotlight division.

About Spotlight: this four-person team is the investigation arm of the paper, committing months on important stories. It consists of editor Walter ‘Robby’ Robinson, Sacha Pfeiffer, Matt Carroll, and Mike Rezendes, and they report to deputy managing editor, Ben Bradlee Jr. (his father was the editor who helped break the Watergate story for The Washington Post). Hints are given about their personal lives, especially where their faith is connected— Sacha is married and occasionally goes to Church for the sake of her Nana; Matt is a family man who goes to his wife’s Presbyterian church; Mike is in a marital rough patch and lives in a temporary apartment because he spends more time at his job; and Robby has connections to important people partly because he grew up with many of them. This is a rarity because the script doesn’t let their personal lives get in the way of the real story: learning how the Church covered its tracks.

Heading into Act 2, the team divides up the work. Mike works with the lawyer, Mitch Garabedian, a no-nonsense Armenian who is fighting hard to get justice for his victims; Sacha interviews survivors; Matt digs through books and files to see if anything can be found in the records; and Robby oversees them, while witnessing first-hand how his community is unwilling to confront the uncomfortable truth, and how they turn away from him because he’s shaking it up. Like a puzzle slowly taking shape, the pieces fall into place heading into Act 3, as the individual narrative threads converge and the Spotlight team race to assemble the story. When they finish, all of them are personally shaken to the core.

Spotlight works in the vein of a mystery story. It plays out the reveals each time the team finds a clue that sends them deeper into the extent of the cover-up. Obstacles pop up to derail them; the Church, for one, though they remain largely in the background. The two most pressing concerns are the deadlines— can Spotlight gather enough evidence to build a substantial piece of reporting or should they kill the story?— and also the danger of being pulled off to work on something else, which temporarily happens on 9/11.

The other obstacles include getting people willing to talk on records, and finding the necessary proof to expose the system. But these challenges push the narrative into a bigger pursuit: Instead of focusing on exposing 13 priests as planned, they realize they have to nab 90 priests!

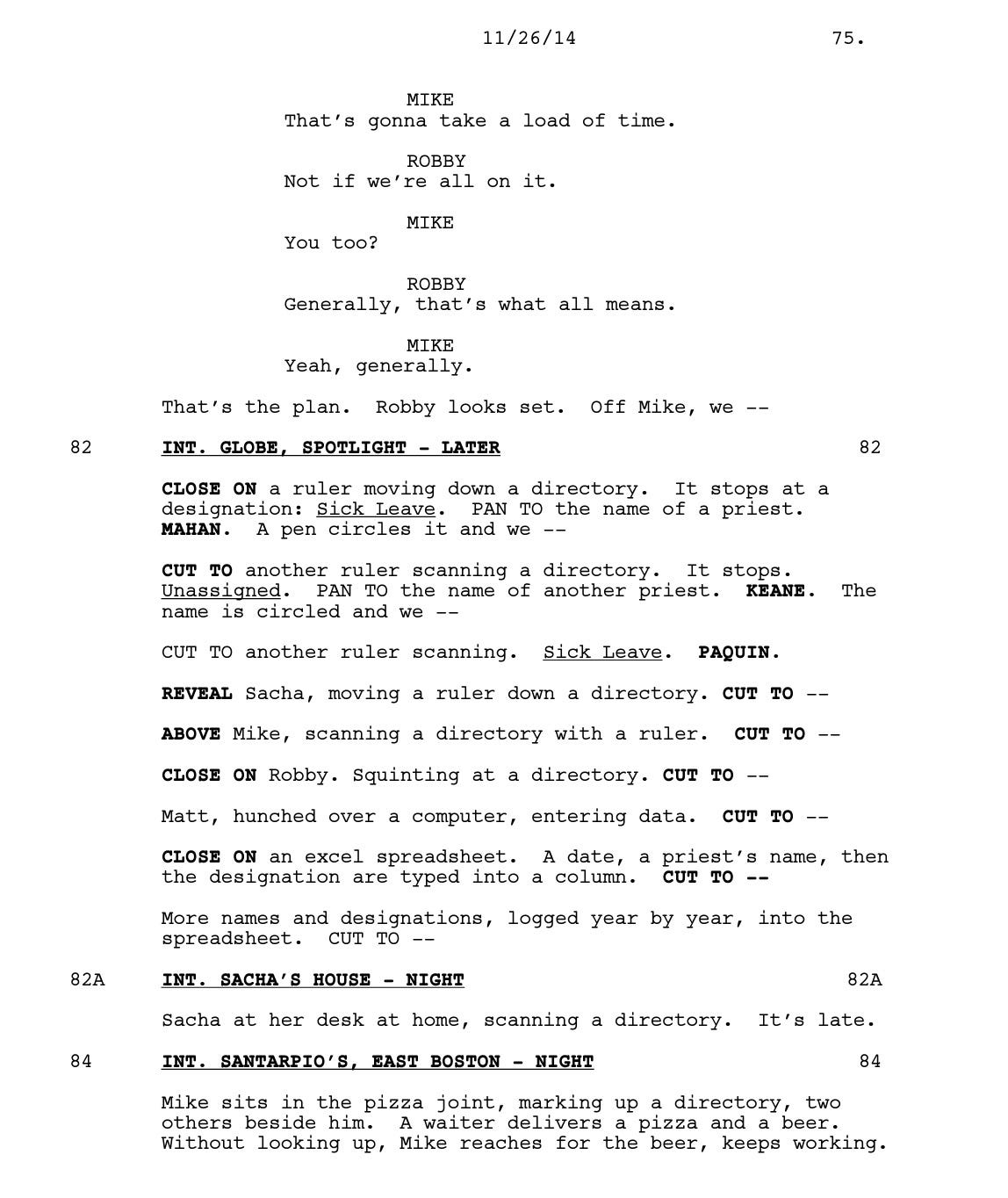

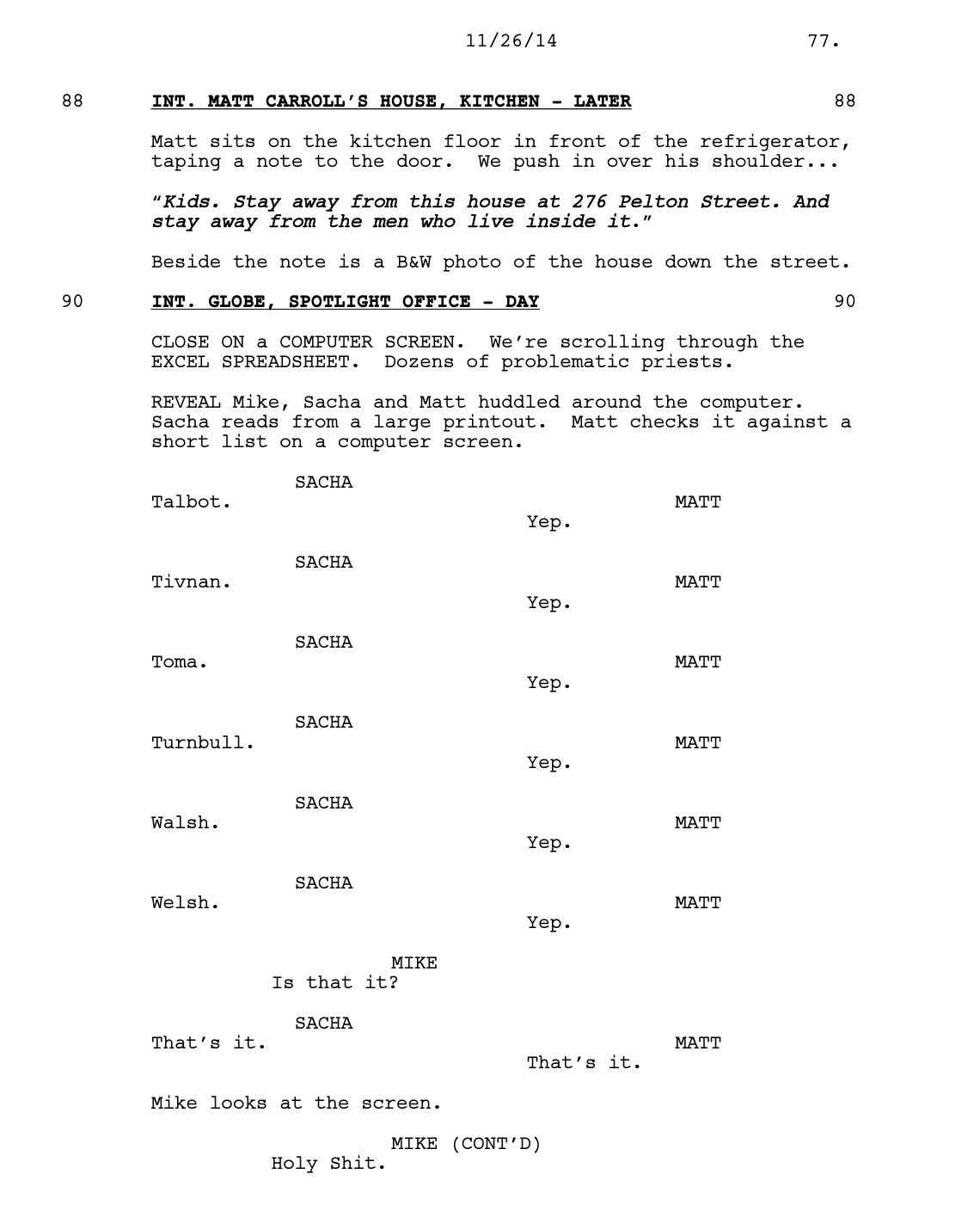

Spotlight retains our attention using strong prose to create imagery. Writers Josh Singer and Tom McCarthy use a host of techniques to sustain the energy and turn the nuts-and-bolts of investigative journalism into good cinema, such as montages and evocative visuals…

Another example:

And another:

Maybe it’s just me but I love the fact that this entire screenplay can be considered an ode to hard work, especially in the scenes where they frantically work long hours to file the story.

It’s also great at building tension and suspense with an easy naturalism. Take, for instance, Scene 104—Sacha visits a retired priest, Father Paquin, to asks some questions; the awkwardness of the situation has the potential to combust… right up to the bit when he straight-up admits to molesting boys. Then the scene takes a turn when Father Paquin reveals that he was raped as a boy.

Another great example of compelling writing in Spotlight comes in Scenes 86-88; learning that priests are sent to treatment centers when caught, the team start tracking down the houses, and Matt discovers that one treatment center is in the area where he lives.

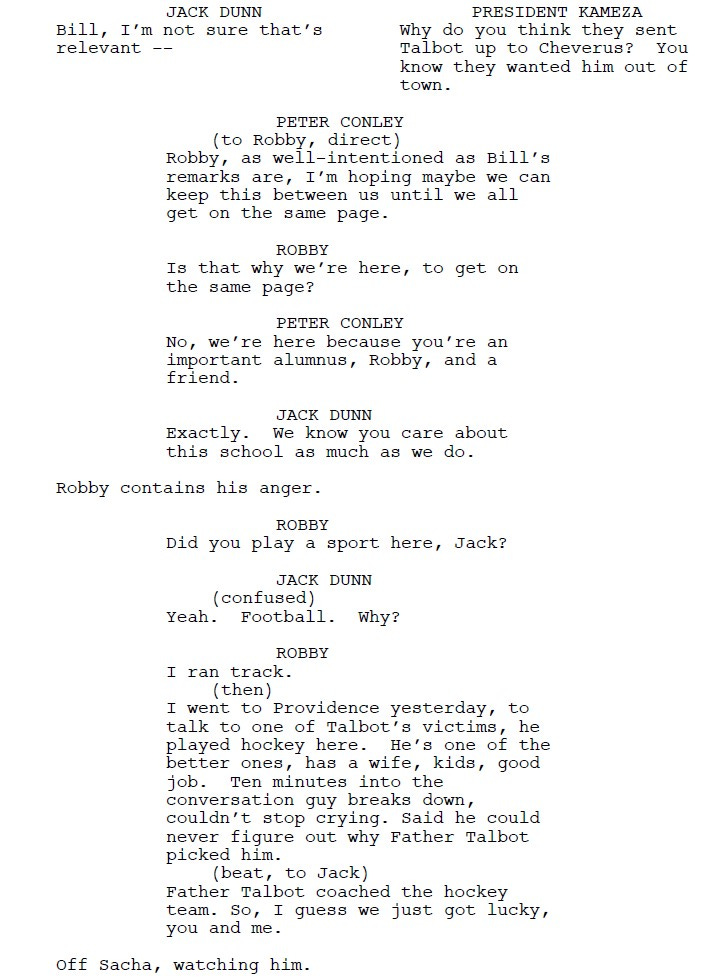

If the A-story is the investigation, then the B-story is the emotional reactions to the discoveries. Although this is an ensemble piece, Robby is the character hit hardest. This comes through in two ways. One is when Robby bites his anger to tell his alma mater spokesman that the two of them, who played sports as kids at the high school, only escaped being victims because they weren’t on the hockey team coached by a predatory priest.

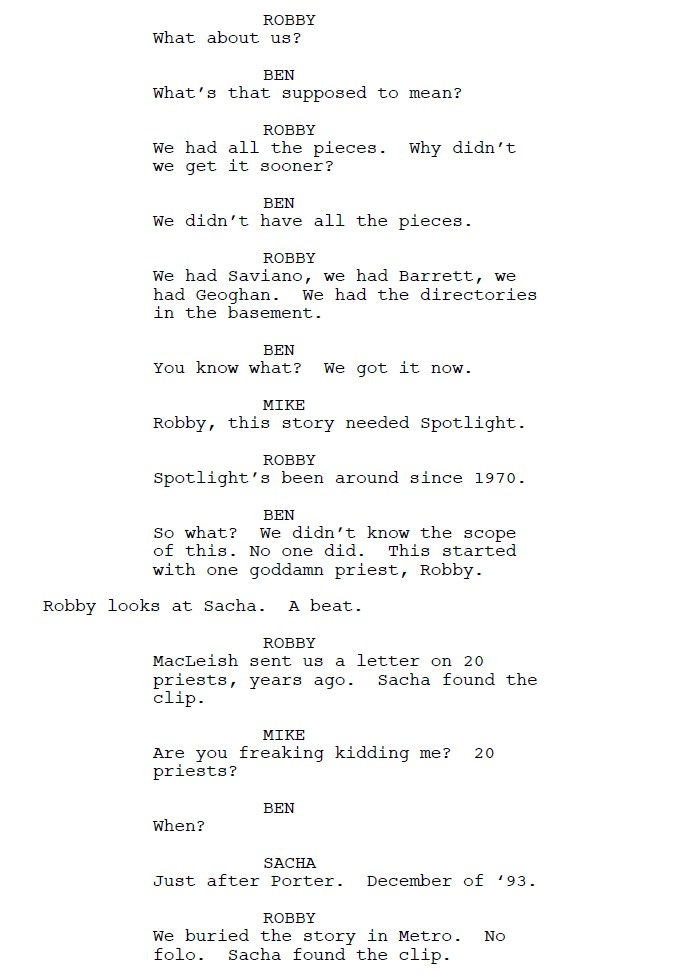

The second comes towards the climax, when Robby beats himself up for not pushing harder a decade earlier when a lawyer sent a list of 20 names and the Globe buried the story; more accurately, Robby buried the story except he has no memory of it.

The beauty of Spotlight is that it plays these emotional moments with restraint, without spilling into melodrama. Two other powerful moments include a charged confrontation between Mike and Robby when the former lets loose at his editor…

And a conversation over dinner between Garabedian and Mike, in which the lawyer makes a pointed observation about complicity and why a community needs outsiders to shake it out of complacency.

McCarthy initially declined to make Spotlight; later, he changed his mind when he saw Marty Baron similar to Clint Eastwood’s The Man With No Name, walking into town and turning it upside down. A Catholic himself, McCarthy refrained from turning the story into an attack on the Church; instead, he turns Spotlight into a pointed argument about moral corruption in institutions and the power of journalism to hold the corrupt accountable on behalf of the public. His co-writer, Singer, laments that the latter has largely disappeared as the internet disemboweled the financial health of journalism. Together, the writers waded through piles of information and wrote several drafts to get it right. Sometimes, this meant working directly from the transcripts with survivors, and using “actual” dialogue for scenes. Doing so can be a powerful writing tool.

The result is a screenplay that is stolid, formidable, and allows this true story to play without artifice. It takes a lot to make investigative journalism exciting for the layperson, and Singer and McCarthy have succeeded; they deserved to win the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. And it was no small feat— the other contenders included Bridge of Spies, Straight Outta Compton, and also two scripts featured on the WGA’s List of Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century, Ex Machina and Inside Out.

It doesn’t resort to clichés to build excitement, nor does it invent scandal for the characters to create unnecessary drama. (It’s also depressing to point out that this is the rare exception when a script does its female journalist right by NOT having her sleep with a source! See: House of Cards, Sharp Objects, Trainwreck, Thank You For Smoking, Never Been Kissed, Iron Man)

Stories like Spotlight matter, even if they aren’t exactly commercially appealing. They remind us that a bunch of hard-working and intelligent people can make a difference; sometimes, the pen truly is mightier than the sword.

Notes:

Iacovetti, Carla (January 25, 2016) | Spotlight: The Burden of Truth (Creative Screenwriting)

Blyth, Antonia (February 6, 2016) | ‘Spotlight’s Tom McCarthy: “I Passed The First Time” (Deadline)