Ex Machina (2014) Script Review | #50 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A disquieting and first-rate thriller about artificial intelligence that feels prescient even more than when Alex Garland wrote it.

Logline: A 26-year-old coder at the world’s largest internet company wins a competition to spend a week with the company’s reclusive CEO at a private mountain retreat, but discovers that he has been picked to participate in a strange and fascinating experiment: to interact with the world’s first true artificial intelligence, housed in the body of a beautiful robot girl.

Written by: Alex Garland

Pages: 115

Scenes: 124

Characters:

Ava

Caleb

Nathan

Kyoko

The most striking thing about the Ex Machina screenplay is its indie-like attributes— a handful of characters and a single location– that allow writer Alex Garland to craft a satisfyingly lean and cerebral screenplay. It’s a great template for first-time filmmakers and aspiring screenwriters to emulate, as it uses its limitations to tell a compelling story that, as you can see, we are still discussing nearly a decade later.

Shy coder Caleb wins a company lottery to spend a week with the founder of Blue Book, Nathan. It is implied that in this world, Blue Book is analogous to Google. On arriving at Nathan’s private retreat, Caleb soon realizes that it’s not going to be a holiday: he’s been chosen to test if Ava, an artificial intelligence (AI) housed in the body of an attractive young woman, can pass off as human. But as the week progresses, Caleb’s feelings about Ava become complicated as he discovers Nathan’s secrets, climaxing in a bloody payoff that still shocks.

What is that payoff? Ava tricks Caleb into falling in love with her in order to secure her freedom, stabs Nathan, and leaves the resort– with Caleb trapped inside with no way to escape.

That ending might seem as if the villain won and got away, but Garland actually wrote Ava as the script’s secret protagonist. In the light of her fate, Ava’s character arc parallels that of Andy Dufresne in The Shawshank Redemption, making Ex Machina a secret prison break movie all along. Garland has not made it a secret that his sympathies lay with the female character; Nathan is the typical tech-bro founder who is callous in his attempts to be Prometheus, and Caleb, despite his sympathy to Ava, is not free from complicity. We feel for his fate, but as with Victor Frankenstein, this is what comes from trying to play God. Isn’t it interesting how real-life advances in AI— largely driven by males— tend to downplay its scary potential by disguising it in the persona of a female? Look no closer than the OpenAI fiasco, where Sam Altman thought releasing a virtual assistant version of ChatGPT that sounded like a flirty Scarlett Johannson would be a good idea (in Ron Howard voice: It wasn’t). How you feel about Ava, ultimately, says how you feel about humanity.

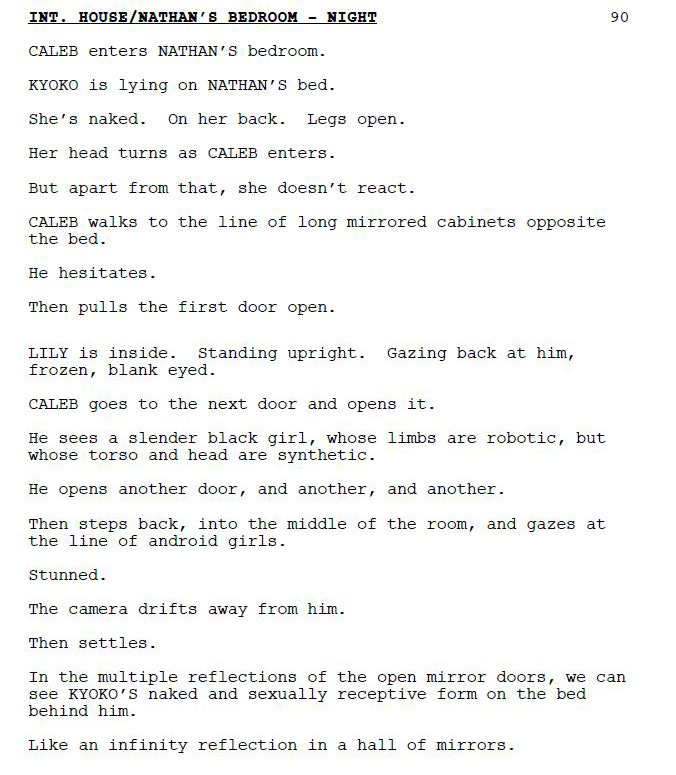

Although it is more of a thriller, one can argue that Ex Machina borrows significantly from the structure of a horror movie; according to Blake Snyder, it would fall squarely in the ‘Monster in the House’ template (the resort is the house, the ‘monster’ is Ava, and the sin being committed is attempting to create life). Of course, turning the ‘monster’ into the real protagonist is a delicious subversion. The story is also heavily influenced by the Bluebeard fairytale, in which a newlywed wife discovers that her husband has kept the dead bodies of his previous wives locked in a closet. In scene 90 on page 91 and 92, Caleb discovers the bodies of the previous AI versions in Nathan’s closet.

What is the Act Structure of Ex Machina?

How has Garland structured the story? Given that it spans a week, each day covers a new development, each more unsettling than the last. Observe:

Day 1 – Caleb arrives, meets Nathan, meets Ava for the first time

Day 2 – Ava asks Caleb about his background and warns him not to trust Nathan

Day 3 – Caleb conflicted about his feelings for Ava as she continues to seduce him

Day 4 – Caleb taken to Nathan’s lab, discovers that he was brought to test out the AI, Nathan covertly bugs Ava’s room

Day 5 – Ava tests Caleb, worries about her fate if she fails, Caleb changes the security codes and discovers the bodies of the previous AIs

Day 6 – Caleb and Nathan face off, Nathan is killed, Ava escapes

By page count, the act structure is as follows:

Act 1: page 1–29

Act 2: page 30–107

Act 3: page 108–115

Act 1 is devoted to Day 1, while the bulk of the screenplay lies in Act 2 which covers Day 2 to Day 6, while Act 3 is the last bit of Day 6 and moves to a swift end. In fact, the finished film moves even faster than the script, removing the scenes between Caleb and the chauffeur on pages 4-6 (and changing it from travelling by car to a helicopter). Why? Because the information relayed in those pages gets covered later more or less in Caleb’s interactions with Ava.

Let’s study Act 2 more closely. On Day 2, Ava takes advantage of a power failure to warn Caleb not to trust Nathan. The Midpoint of the script occurs around Day 3, when Caleb begins to develop feelings for Ava. On Day 4, the ground begins to shift– as Caleb becomes more susceptible to Ava’s seduction, Nathan takes him to the lab to remind him that Ava is not a person but a machine; Nathan also secretly bugs Ava’s room to listen in on their conversations. (It’s also the Day on which Nathan and Kyoko dance in a scene that has since become famous).

On Day 5, Ava tests Caleb and expresses her fear about her fate; that same night, Caleb swipes Nathan’s keycard and also discovers the ‘bodies.’ Day 6, Caleb’s final day before he departs in 24 hours, Nathan reveals that he knew what Caleb was up to until Caleb surprises him with the reveal that he already changed the codes that would allow Ava to escape her room. The remainder of Day 6 forms Act 3, during which Nathan is killed between Ava and Kyoko, Nathan’s other AI creation.

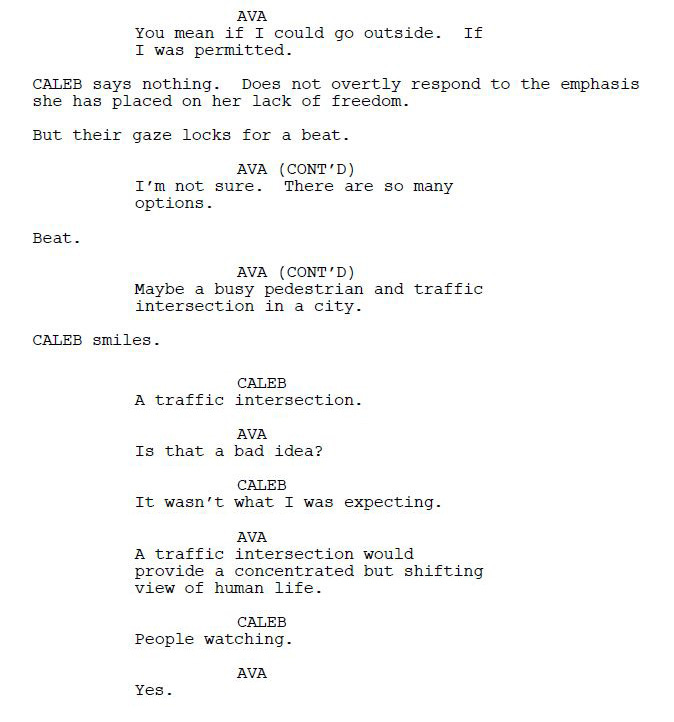

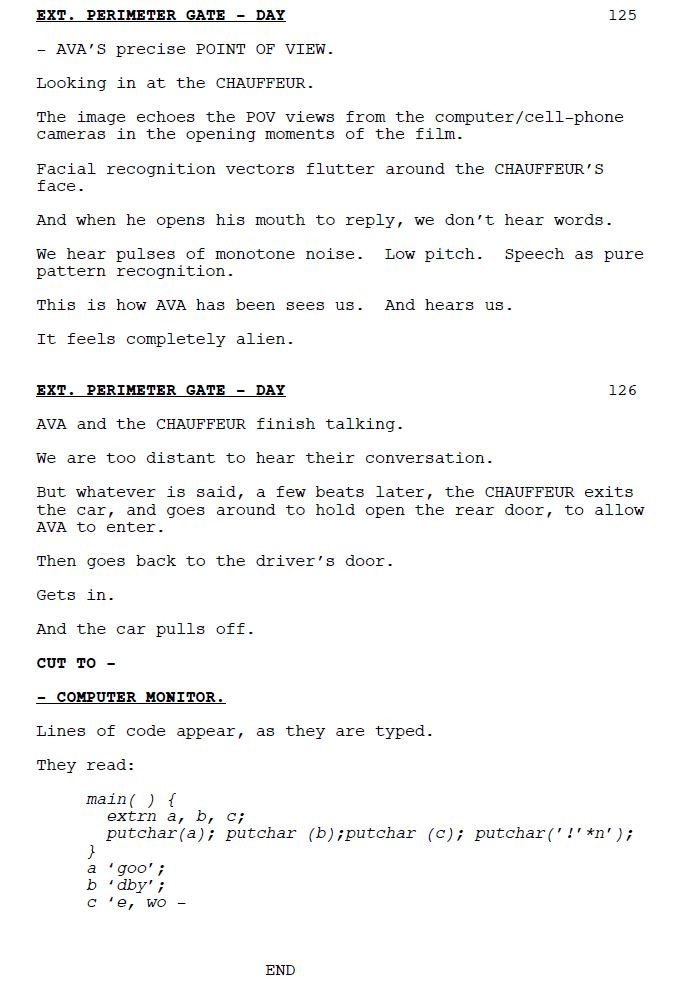

The screenplay’s ending differs from the version that was filmed. In the script, Ava meets the chauffeur assigned to take Caleb and convinces him to take her instead, and it’s mostly seen through her literal point-of-view, showing how Ava sees the world (i.e. it’s like the first-person shots of the T-1000 in the Terminator movies). The film, however, ends with Ava standing at a traffic intersection, indistinguishable from the people moving all around her, implying that the AI is among humans. It’s a callback to a line of dialogue on pages 53-54, and a much more impactful image to end on. The latter ending also embraces Garland’s penchant for uncertainty—he hates certainty, because it results in endings that are too neat.

What makes Ex Machina intriguing is its intelligent approach to the topic of AI– the entire story is essentially a Turing Test and other hypothetical scenarios filtered through the lens of fiction. Observe the discussions between Nathan and Caleb, and Caleb and Ava, and you’ll notice that rarely do screenplays have two characters engaging in high-level discourse.

It’s also remarkable that Caleb, who is presented as the protagonist, is a very passive character until near the end of Act 2. He mostly reacts instead of taking charge, something that many screenwriters would advise against. But here, the passivity works, and I reckon it’s because when you consider Ava as the real protagonist, you discover that she has been active in causing events to develop. Caleb is, for lack of a better word, a pseudo-protagonist.

Garland has an evocative yet sparse writing style. His action lines are brief, and he only writes large paragraphs when required. In some instances, the pages are taken up by long exchanges; in other instances, pages run without dialogue. The result is a script that has plenty of white space and is fast to read. Most of all, it’s a screenplay that slowly builds to its conclusion, tightening the dread and tension without easing up. A chamber piece that is taut with suspense.

The origins of Ex Machina can be traced back to Garland’s boyhood days, when he did some basic coding experiments on the family computer at the age of 11-12. Although the results were basic, he couldn’t shake off the impression that he had just interacted with a device that seemed to have a mind of its own. Garland would continue his research, estimating that he spent at least a decade studying the subject of AI, from reading dense textbooks such as Machine Language to watching Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. He also consulted various experts on the topic, building up his knowledge before he wrote the screenplay.

One glance at Garland’s track record and it becomes obvious that he has always had a preference for tackling heady topics disguised as entertainment. This thread runs through his entire filmography, from 28 Days Later to Ex Machina; even his adaptations of Never Let Me Go, Dredd, and Annihilation carry this hallmark. Different stories, yet they each share a common interest in the humanity of characters in scenarios that have a sci-fi bent. In Ex Machina— for which Garland received his first Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay– he sees the creation of Ava as an almost parental act. And children, of course, grow up into their own beings. Even if the ending is ambiguous, Garland leaves little room for doubt on whose side he is on in: he’s on the side of the machine.

Notes:

Lewis, Helen (22 January, 2015) | Alex Garland’s Ex Machina: can a film about an attractive robot be feminist science fiction? (The New Statesman)

Quirke, Antonia (16 January, 2015) | Interview: Alex Garland on his new venture ‘Ex Machina’ (Financial Times)

Patches, Matt (25 April, 2015) | Liked Ex Machina? Check Out the Books and Films That Inspired the Year's Best Sci-Fi Movie (Esquire)

McKittrick, Christopher (6 January, 2016) | Alex Garland on Screenwriting (Creative Screenwriting)