Inside Out (2015) Script Review | #29 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Charming and powerful, Pixar strikes again with a poignant story about how emotions work, but Pixar-style.

Logline: After young Riley is uprooted from her Midwest life and moved to San Francisco, her emotions- Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust, and Anger- conflict on how best to navigate a new city, house, and school.

Written by: Pete Docter, Meg LeFauve, Josh Cooley

Story by: Pete Docter, Ronnie Del Carmen

Pages: 129

Inside Out takes an abstract and bold conceit— how the emotions inside our heads work— and turns it into a thoughtful and funny story.

The rules of the world are as follows: Inside each person reside the following anthropomorphized emotions— Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust; they live within Headquarters and carry out all the functions connected to that person’s emotions. Memories are stored in orbs that can be replayed like a spherical video recorder; personalities are visualized as islands that can crumble if things go wrong; dreaming takes the form of a film studio lot; and disused memories fall into an abyss and fade away. With me so far?

The screenplay’s protagonist is eleven-year-old Riley Andersen. When her father sets up a new venture in San Francisco, Riley is forced to move from her hometown of Minnesota; this triggers a series of escalating conflicts that Joy and the others in Headquarters must tackle. Things only get worse when Joy and Sadness get accidentally sent to the other side of Riley’s mind, forcing them to work together and return to Headquarters before Riley sinks into a deep depression.

The story alternates between Joy and Sadness inside Riley’s head, and Riley in the real world. All the required information is frontloaded in the first 10 pages in an engaging, and often uproarious, manner; it quickly outlines the necessary rules of the world while introducing the Andersens, only known as Mum and Dad, and the other three emotions. For a Pixar story, this has a surprisingly small cast of characters; even the first Toy Story had more. The rules orient us to the world we are about to enter, and cleverly turns the way emotions work into a cutesy visualization.

Joy and Sadness get stranded outside Headquarters around page 44, and from then on, the pair are wanderers traveling through the eleven-year-old’s mental landscape. What’s incredible is how the writers manage to convey this in as few lines as possible; for instance, the way they talk about abstract thought.

The journey to turn Inside Out from an idea to a final script was fraught with false starts and changes. The first inklings of a potential story came to Pete Docter when he noticed that his daughter turned from a goofy kid to a quiet and serious one around the same age as Riley, and wondered what was going on inside her head. This led to months of discussions and research, but the most crucial point to start off with was: whose mind would they explore and what would they find? Since the inspiration began with Docter’s daughter, the protagonist would be a young girl. This was also serendipitous with research that confirmed girls were better attuned to gauging social situations and tend to mature faster than boys. To ensure the project captured the authenticity of an 11-year-old girl, Docter staffed at least half his story crew with women. The team spoke to neurologists, brain surgeons, and many others to get the science correct, working furiously at their whiteboards as they toyed with concepts and character relationships. Time taken simply to figure out the story: a whole year; the material was far too complex for a single script. Early drafts included several emotions as Hope, Pride, Ennui, and Envy (the latter two appear in the sequel, Inside Out 2); for a long time, Pride was in the story as a fifth emotion until the team narrowed it down to four.

Alas, their work was hardly done; it had barely begun! Two problems puzzled the team throughout: the first was turning Joy into a likeable character, as her domineering personality could rub off the wrong way. Heck, even in the final draft, a trace of this is still there. One way to make her seem more relatable was to make her appear as if she was acting in Riley’s best interests— such as the scenes when Joy struggled to make Riley happy when there were reasons not to be.

Initial drafts also had Joy becoming an obstacle to Riley growing up, putting the character in embarrassing situations by behaving inappropriately. Other discarded ideas included Riley wanting the lead role as a turkey in a Thanksgiving Day pageant; at this early stage, the story was still based in Minnesota. But nothing clicked until the idea to relocate to an entire city helped usher the story slowly into view.

There was still a second problem, though. For a good deal of time, Fear was originally paired with Joy to be her travel companion; yet, the story wasn’t working, and deadlines were starting to loom. In 2013, two years prior to the film’s release, Docter took a stroll in the hopes that a walk would help unravel this thorny problem. What could Joy learn from Fear in order to grow?

Almost as if this was a Pixar movie, a lightbulb went off. Docter realized that people weren’t meant to be happy all the time; in fact, sadness sometimes brought people closer together. Instead of pairing Joy with Fear, she ought to team up with Sadness! It was a real eureka moment with a not-so-tiny catch: They were three-and-a-half years into production; to swap characters and overhaul the relationship would create additional work.

Luckily, Pixar’s then-chiefs, Ed Catmull and John Lasseter, accepted Docter’s arguments to change course and granted the team the time necessary to carry this out. It was during this period that Meg LeFauve joined the team. After 10 plot rewrites and several drafts, Inside Out finally fell into place. Along with LeFauve, the screenplay would be credited to Docter and Josh Cooley, while Docter and co-director Ronnie del Carmen received credit for the original story.

This anecdote offers one of several lessons for writers seeking to write ambitious stories:

Spend time setting up the rules of the world— Andrew Stanton made this recommendation to the team early in discussions, especially on how memories and emotions change over time as the brain gets older; this was taken to heart as the first 10 pages effectively accomplished this, as mentioned in a few paragraphs earlier.

Keep it simple— Despite the abundance of research, information, and possibilities that the premise offered, the writers narrowed it down to a simple idea: how does relocating to a new place affect a character? They also trimmed the cast of emotional characters to four to ensure that the audience understood what was happening; in real life, there are way more emotions in our head than just Joy, Fear, Sadness, Anger and Disgust.

“You can’t rush art!”— Prophetically declared in Toy Story 2, Inside Out is the clearest beneficiary of taking the time to change the story in several directions until it found the right narrative. Had Pixar rushed production or refused Docter’s entreats to change a core relationship after three years of development, the script would not be as strong to merit its inclusion on this list. Sometimes, it takes a while to discover what and how you want to tell the story.

Use personal experiences to add personality— Quick, name 10 movies off the top of your head that feature a 11-year-old female protagonist! Coming up empty? That’s because a character like Riley Andersen is rare in the movies. The idea to have Riley love hockey originated because it was a popular sport in Minnesota among kids. Likewise, the goofball element of Riley’s personality came from del Carmen’s experience as a parent, especially a brief moment when toddler Riley runs naked around the house after a bath.

When stuck, take time away from the story— just as Docter stumbled on his valuable insight on a walk, many artists have discovered the benefits of movement to stoke creative thinking; Dickens averaged 12 miles a day walking, no doubt during which he came up with half his plots and characters; in On Writing, Stephen King shares how he solved a story problem when working on The Stand while on a walk. If you are struggling on a story or a piece of work, a little time away can bring in perspective, helping to see the forest for the trees.

Research, research, and more research— many details in Inside Out, such as the way memories are encoded and how thoughts become abstract, originated from actual research. Pixar teams are famous for immersing themselves in the environments of their story to bring in authenticity to the details (for Finding Nemo, they went scuba-diving; for Ratatouille, they spent time in a fine-dining kitchen and spoke to Chef Thomas Keller). It is the proof that when science and art come together, interesting things can be created.

The final result truly is fascinating to read. Look at how action scenes are written…

… or how it avoids repeating pieces of dialogue such as song lyrics…

… and how it effectively describes a series of shots.

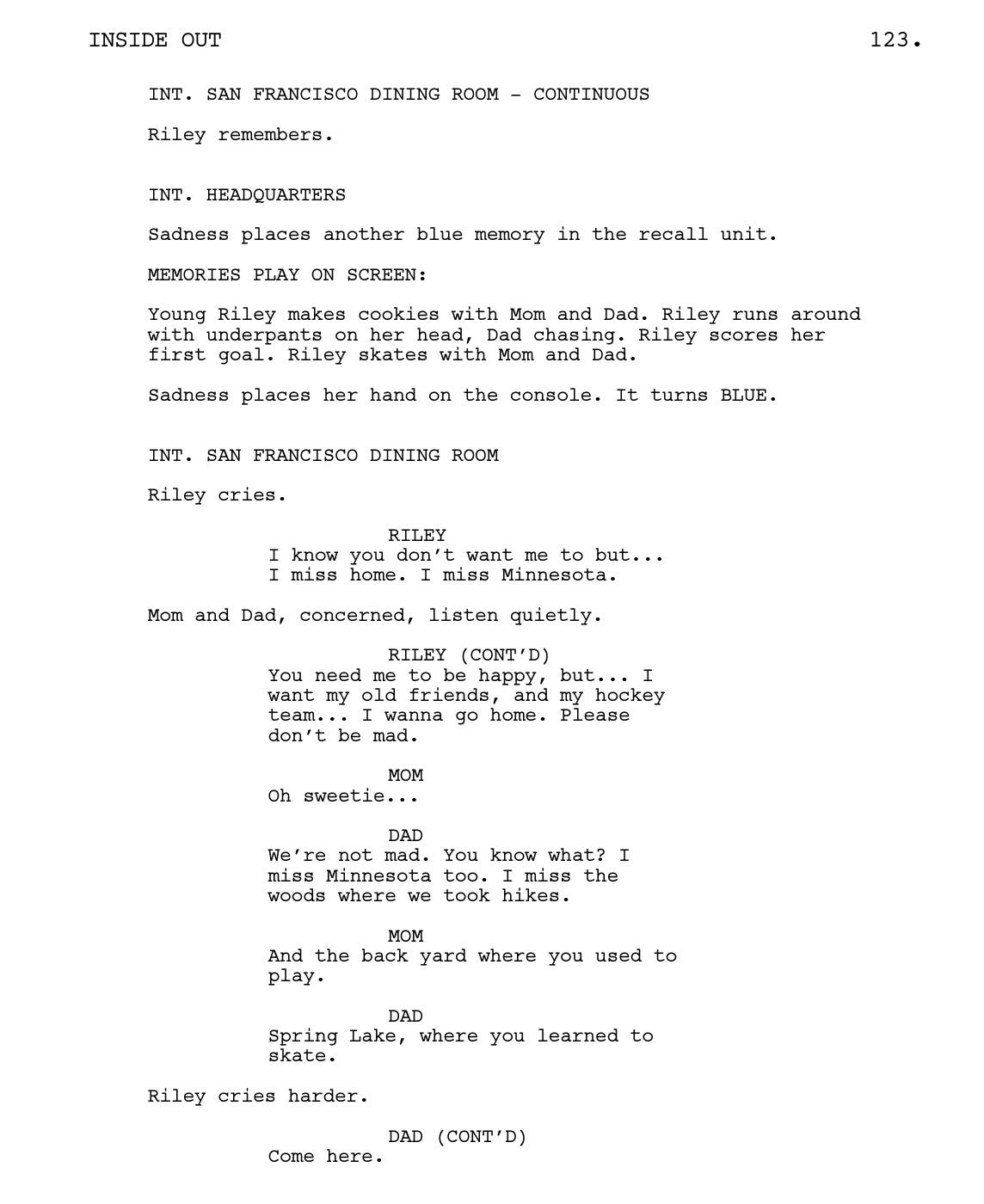

Even the climax when Riley breaks down in front of her parents is written with electrifying simplicity.

With the right amount of time and craftsmanship, it is possible to take daunting, ambitious ideas like Inside Out, and spin them into powerful stories. That right there is real magic.

Notes:

Catmull, Ed; Wallace, Amy (2014) | Creativity Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (Updated Edition)

Bishop, Bryan (June 17, 2015) | Inside Out: how the director of Up made Pixar’s wildest movie yet (The Verge)

Barnes, Brooks (May 20, 2015) | ‘Inside Out,’ Pixar’s New Movie From Pete Docter, Goes Inside the Mind (The New York Times)

McKittrick, Christopher (February 16, 2016) | “Is this the best story we can tell?” – Inside Out (Creative Screenwriting)

Women Hollywood (June 11, 2015) | Why Pixar Whiz Pete Docter Decided to Enter a Young Girl’s Mind — and Turn Your Emotions Inside Out (Women and Hollywood)

Giardina, Carolyn (December 21, 2015) | Making of ‘Inside Out’: Which Emotions Didn’t Make the Cut (The Hollywood Reporter)

Thompson, Anne (December 3, 2015) | Why Pete Docter’s Oscar Frontrunner ‘Inside Out’ Was So Tough to Make Into Must-See Pixar (Indiewire)

Desowitz, Bill (October 29, 2015) | Immersed in Movies: Talking the Adult Appeal of Pixar’s ‘Inside Out’ (Indiewire)