Lady Bird (2017) Script Review | #16 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Warm, subtle, and insightful, Greta Gerwig creates a funny and realistic portrayal of a young girl on the cusp of adulthood.

Logline: A California high school student plans to escape her family and small town by going to college in New York.

Written by: Greta Gerwig

Pages: 110

As far as coming-of-age stories go, Lady Bird is a riot. A female-centric counterreaction to similar male-centric features like François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows or Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, Greta Gerwig has created a thoughtful, complex, and funny screenplay about a girl who wants to “leave a place that’s secretly a love letter to the place… and ostensibly about a daughter that’s secretly about the mother.”

Christine ‘Lady Bird’ McPherson is an intelligent though bratty teenager from Sacramento who dreams of leaving her home town and moving to New York (even though her family cannot afford the tuition). This is her last year at a private Catholic school that she attends with her best friend, Julie Pickett. During these months, Lady Bird will take part in a play, fall in love with two different boys, nearly jeopardize her friendship with Julie, and butt heads constantly with her mother, Marian.

The heart of this screenplay is the mother-daughter relationship. A lot is happening, but without it, the story would be noticeably lacking. Gerwig refuses to let it sink into sentimentality; but they have enough clashes that people who grew up with sisters or was the daughter in the family would recognize in their own lives. It’s hilarious— literally—how conversations between Lady Bird and her mother, Marian, escalate into conflicts.

At 110 pages, the Lady Bird screenplay neatly breaks into two parts. The first part, from pages 1-49, covers the first semester of Lady Bird’s life and comprises of Act 1 and half of Act 2. The second part, from pages 50-110, focuses on the protagonist’s slippery slope down towards her last year of school, made up of the second half of Act 2 and the entirety of Act 3. On page 50, the Midpoint, Gerwig cleverly describes what’s going to happen as Lady Bird tries to fit in with the older and wealthier cooler kids; naturally, it did not succeed. Act 3 forces Lady Bird to stand up for herself, repair her friendship with Julie, and focus on leaving for college.

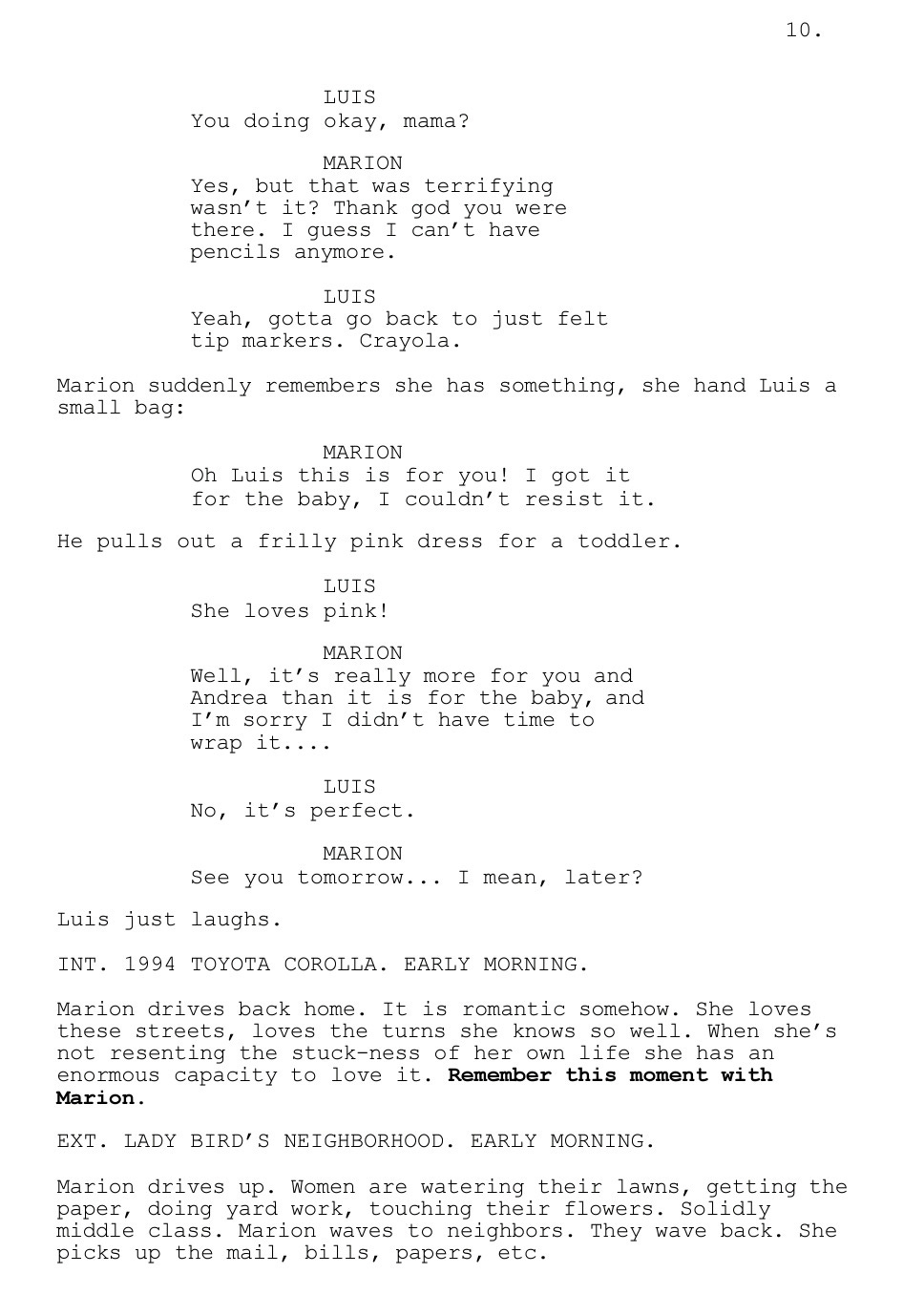

All this makes the story sound dull and somewhat bare, but it’s the opposite: so much happens in the script that it takes a while to unpack. For instance, note how Marion represents Lady Bird’s fate if the latter stays in town. Though it’s never said aloud, Gerwig makes it clear how Marion feels about her own life.

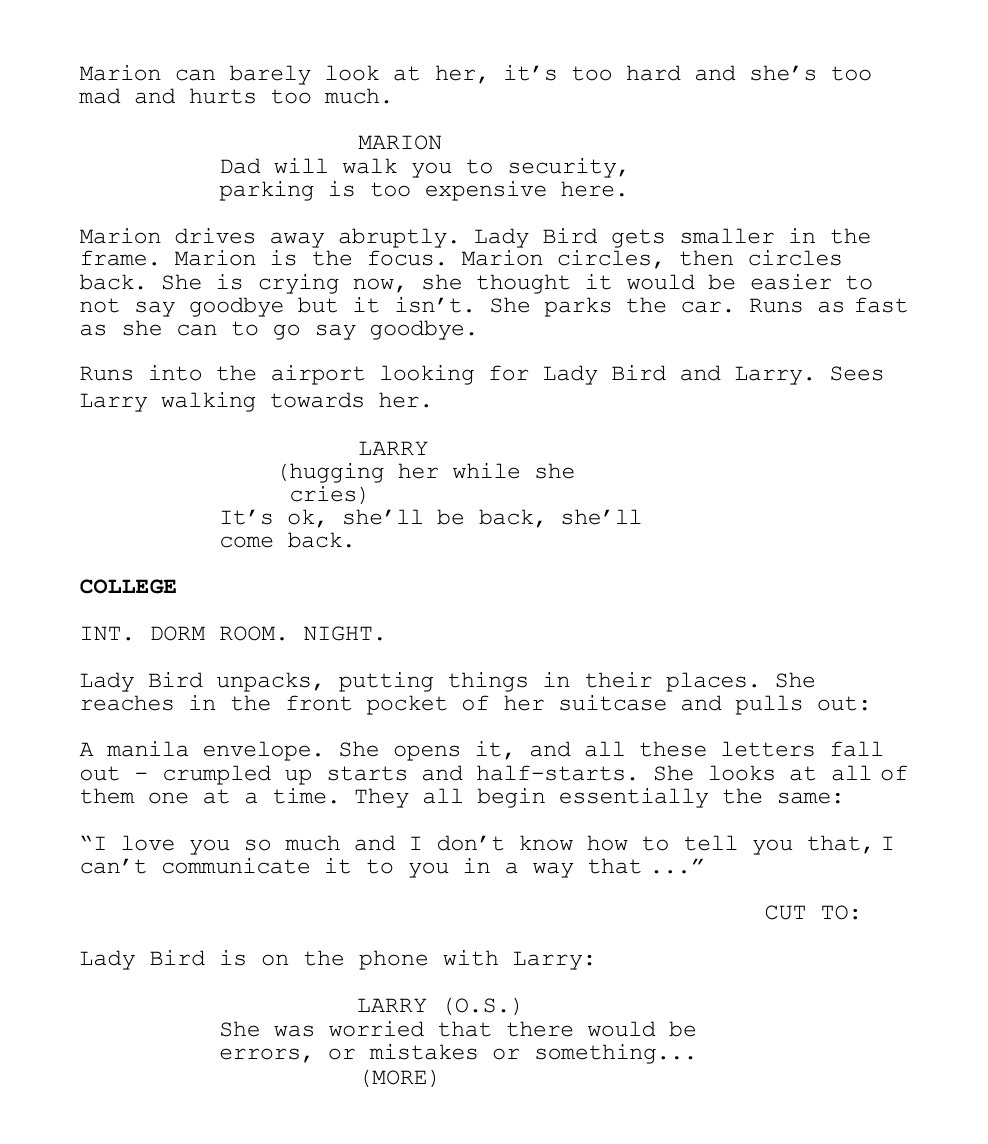

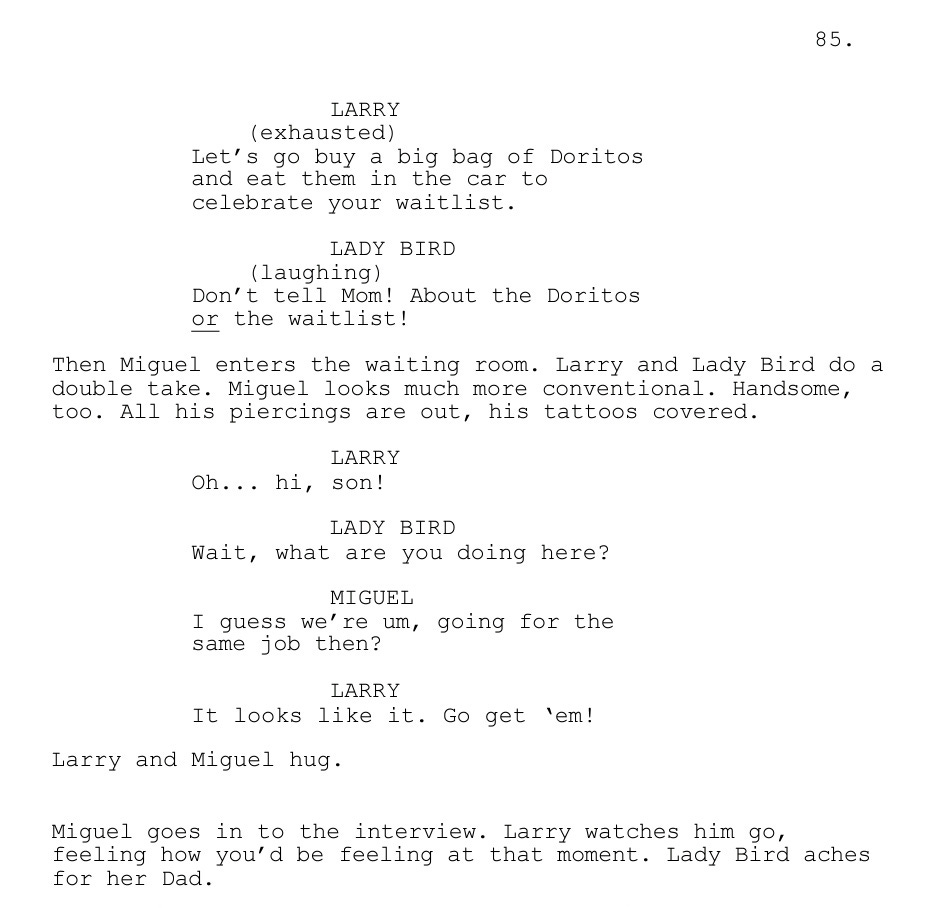

Most of the plot is built on the relationships that Lady Bird has with people. She has a good rapport with her gentler and less confrontational father, Larry; she willingly accompanies him to a job interview, only to discover that her brother is applying for the same job. Look at how Gerwig writes her reaction:

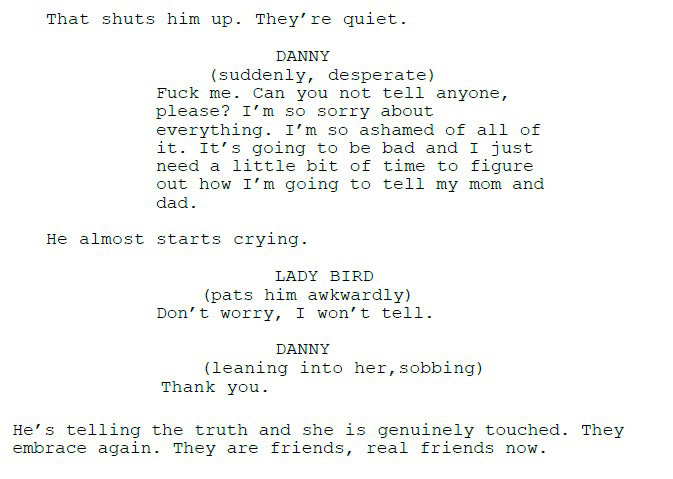

Other subplots include how Lady Bird discovers unexpectedly that her first boyfriend, Danny, is gay, and responds to it; how she loses her virginity to the smart but pretentious Kyle; and gets suspended for making a comment at an assembly against an anti-abortion activist. So much happens, it’s a testament to Gerwig’s skill in never letting it feel cluttered, but instead, flows naturally.

(Note: The relationships with the boys, incidentally, are almost tangential. They are there, but they are not the focus of the journey. That place of honour belongs to Lady Bird and Marion).

The richness stems from Gerwig’s astute prose, as well as the fact that the Lady Bird screenplay—originally titled with the (more) straightforward name, Mothers and Daughters— originally clocked in at 350 pages (Gerwig jokes that it contained more dances). Daunting, expensive, and time-consuming? Yes. But it also helped to “figure out what the story is,” trimming out everything except the parts that Gerwig thought would be best. Else she struggled initially trying to get the narrative working. The title, in fact, originated in 2013-2014, when Gerwig, stuck with writer’s block on a scene, wrote on the top of the page: “Why won’t you call me Lady Bird? You promised you would!” She had no idea where that came from; but decided to follow and see where it led, until she had a screenplay that was not so long.

The writing is great. Gerwig has a more literary in how she allows the characters to develop on the page instead of trying to outline or plot in detail. She would steal bits of dialogue that she’d overhear, such as Lady Bird wistfully wishing early on, “I wish I could live through something.” She mines humor when you least expect it, and leans into the dramatic moments without overplaying her hand. It’s got the impression of a lived-in universe, with so many other stories also unfolding at the same time, such as Father Leviatch checking into a psychological hospital where Marion works. No doubt it was the result of writing all those pages.

I like how Gerwig condenses lengthy scenes into paragraphs, like she does on page 40.

And I love how she finds and nails the balance of dual dialogue, creating a rhythm amid the chaos (note: Gerwig would use dual dialogue similarly in her adaptation of Little Women).

Most of all, I admire how she can sum up an entire relationship in a few lines or words, such as Larry and Marion.

Somehow, Gerwig finds a way to reflect whole worlds and universes of people through the microcosm of Lady Bird. If the chance arrives, as it did for Quentin Tarantino, she can turn this script into a novel and show us what didn’t make the cut.

Like many writers, Gerwig drew from her own personal life to enrich facts about Lady Bird. For instance, Gerwig also lived in Sacramento and went to a private Catholic school; like Lady Bird, she dreamt of moving to New York. She wanted to write female characters that “go too far,” just as countless male characters have been permitted to do so in movies and TV shows. Lady Bird shoplifts magazines, ditches her best friend to fit in with the popular crowd, lies, and hurts her father by getting down a good distance away from school; but she’s still a good person. Just flawed. As a result, Gerwig has created a teenager who feels like a real teenager than movie/TV show teenagers tend to be, in a script that is powerful and funny, sometimes at the same time. Lady Bird, nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, is simply outstanding.

Notes:

Erbland, Kate (October 6, 2017) | Greta Gerwig Explains How Much of Her Charming Coming-of-Age Film ‘Lady Bird’ Was Inspired By Her Own Youth (Indiewire)

Malone, Noreen (October 30, 2017) | Greta Gerwig Is a Director, Not a Muse (Vulture)

Cornish, Audie (February 19, 2018) | Director Greta Gerwig On The Parallels Between Her Life And 'Lady Bird' (NPR)

Bloomenthal, Andrew (November 27, 2017) | INTERVIEW: Greta Gerwig, Writer and Director of Lady Bird (Script Magazine)