Boyhood (2014) Script Review | #59 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Written over 12 years to mimic the growth of one person and his family's ordinary life, which is extraordinary in its own magical way.

Logline: Tracing the years from early childhood to his arrival at college, Mason deals with the ups and down of his life with his divorced parents and sister..

Written by: Richard Linklater

Pages: 181

Among its many remarkable attributes— and Boyhood has many— what stands out sharpest is the way in which the screenplay compresses 12 years of a person’s life into 181 pages to convince you that you have just witnessed an entire person’s childhood. Within these pages, Richard Linklater has written his magnum opus. A rare and wondrous thing, Boyhood is a time capsule and coming-of-age story in equal measure; it strikes the right balance between humanity and drama without hitting any false notes or allowing for melodrama to creep through.

What’s also remarkable is that the characters aren’t ‘remarkable’ in any sense. They aren’t ‘important’ or rise to importance. They are ordinary; they could be you and me. But Linklater treats their lives as if they’re important because they do matter. Everyone has a story to tell, and these are the stories of Mason, his mother Olivia, his sister Samantha, and his father, Mason Sr. It is what a coming-of-age script ought to feel like.

And what is that, exactly? In Boyhood, it is a series of 12 segments, spanning from 2002 to 2013, across which Mason goes from a 6-year-old boy to an 18-year-old young adult. The segments roughly amount to 10-20 pages, and each segment corresponds to a year in his life. It doesn’t follow any screenplay structure, at least not in the strictest sense. There is a skeletal form underneath that guides the story from start to finish; mostly, however, each segment or episode catches up with Mason at a certain point in his life, checking in on his family, while sprinkling enough breadcrumbs to pick up in the next part. In a sense, it’s as if Linklater took a TV show, trimmed down the episodes to 12 crucial points, then strung them together as a feature; but in a manner that feels naturalistic.

How did he accomplish this? Like all audacious ambitions, Linklater started by identifying his end goal, and then working his way backwards. He wanted to cover the story of a parent-child relationship that ends with the child going off to college. Instead of working out every plot point in detail, he prepared the basic plot beats for each character in advance. In this way, he knew in which direction he wanted to send Mason, Olivia, Samantha, and Mason Sr., without always knowing the specifics. He’d write a segment, then work with the actors to shape the material. Mason Sr., for instance, was influenced by both Linklater’s and Ethan Hawke’s father; likewise, Patricia Arquette drew from her mother’s life in creating the Olivia character. He’d shoot that section of the script, edit it, see where it was going, then write the next part— more or less, for 12 years.

Hence, the characters always feel true to their natures. Mason Sr. starts off as a boy who never took adulthood too seriously and ends up fathering a young son much later in life as his first children are almost at an adult age. Olivia, big-hearted and generous as she is, makes a lot of poor choices in men (immature, abusive, and alcoholic respectively). Samantha, the eldest and the smartest, takes after both parents, while Mason seems to be his own person altogether.

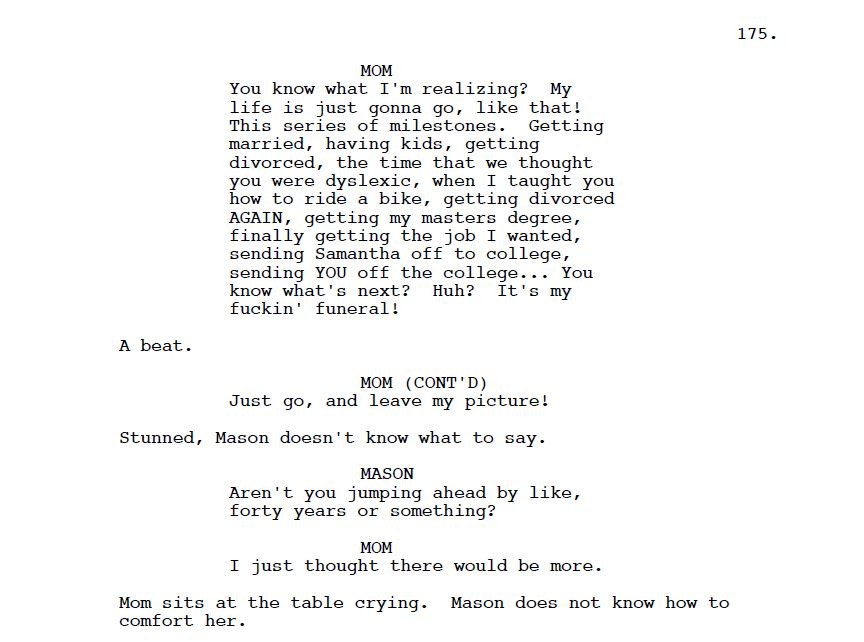

But that doesn’t mean it is wholly untethered from structure. What reads like a naturalistic and improvised screenplay, then, is ultimately the result of a carefully organized, structured plan that only mimics an improvisational tone— a process that he started with Before Sunrise back in 1994. For instance, Boyhood does have a ‘low point’ that usually marks the end of Act Two, which is in the form of Mason’s first breakup. There is a ‘climax’ in which Olivia cries over how quickly life has gone by on page 175.

It’s not conventional, but the rhythm of the structure is there— and that is what separates Linklater from the imitators. He understands that in a screenplay, structure is king. Even if you disguise it underneath a seemingly unstructured story.

The complete screenplay here took Linklater a decade to complete, during which time he wrote and directed a whole bunch of other stuff. The process of writing it intermittently was fundamental to the story. For one, it captures that feeling of passing through life in a manner that could never be pulled off if he wrote it all at once. It also captures the pop culture, and societal and political thoughts, in an almost fossilized state. Take a look at a scene on page 22, where Mason Sr. foreshadows how the Iraq War would end.

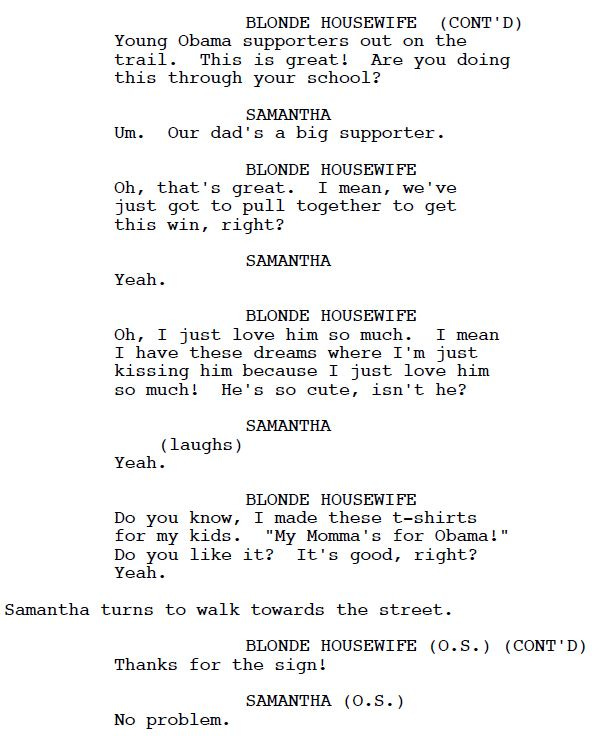

The same applies in capturing the nation’s mood during the runup to the 2008 Presidential election between Barack Obama and John McCain…

… and the way some supporters, uh, show their support for the senator from Chicago.

Other such fossilized pop culture moments include the Harry Potter craze at its peak, in a scene where Olivia reads Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets to Mason and Samantha when they’re small…

… and another when they attend the launch of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince.

Perhaps my favorite was the camping scene on page 84 when Mason Sr. and son discuss the possibility of a sequel to Star Wars - Episode VI: Return of the Jedi.

Ah… if they only knew…

Linklater also forgoes the use of title cards to indicate what year a scene is taking place. He uses the social and pop culture moments to act as anchors; since The Half-Blood Prince came out in 2005, we know the year that the scene is set in. Nor does it use fade outs to note a transition between years. While it can feel disorienting when reading or to keep track, the effect is that we are watching life passing us by.

When it comes to writing naturalistic dialogue, nobody does it better than Linklater (except perhaps Mike Leigh or Ken Loach—and they’re British!). The way he captures the cadence and rhythm of how people talk in real-life without making it flat never ceases to amaze me.

Another:

Like the improvisational style of his stories, the trick is emulate the natural style of everyday dialogue without actually writing everyday dialogue. And like any good piece of dialogue, the dialogue in Linklater’s script is either revealing character or moving the story forward. Take for instance, page 87— look at how the script immediately goes into asking where the character is headed after exchanging ‘hello’s instead of getting mired in inconsequential small talk (as happens in real life).

The same goes with the conversation on page 129— Mason’s first encounter with Sheena only emulates small talk for three or four lines before Mason vocalizes his thoughts about something.

While the screenplay could have simply coasted on its ’12 years in a life’ gimmick, Boyhood goes far beyond that. It is as ambitious and high concept as a big-budget studio tentpole feature; as gentle and moving as a Linklater picture often turns out to be. It is a compassionate snapshot of a Texas family, capturing their joys and struggles, their happiness and their sorrows. The screenplay captures the feeling of growing up without feeling artificial. It might be the most ambitious material Linklater has written in his career (and that is discounting his staggering adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along to be filmed across 20 years!). We are blessed to see the results of it.

Notes:

McKittrick, Christopher (December 29, 2014) “I want to tell a story in a new way” – Linklater on Boyhood | Creative Screenwriting

Chang, Justin (June 25, 2014) Richard Linklater on ‘Boyhood,’ the ‘Before’ Trilogy and the Luxury of Time | Variety

Stern, Marlow (July 10, 2014) The Making of ‘Boyhood’: Richard Linklater’s 12-Year Journey to Create An American Masterpiece | The Daily Beast