Little Women (2019) Script Review | #89 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Greta Gerwig puts a fresh and lively spin on her adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's beloved novel, making her version simultaneously contemporary and timeless.

Logline: Jo March reflects back and forth on her life, telling the beloved story of the March sisters - four young women, each determined to live life on her own terms.

Written by: Greta Gerwig

Based on: Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Pages: 122

Before I start, I should come clean: I’ve never read Little Women. The novel, I mean. I’ve heard a lot of great things about the Louisa May Alcott novel, so naturally, I stayed away. I disclose this detail because I am measuring the worth of this screenplay on its own merits than as an adaptation. I’ve also never seen any of the other many adaptations out there (there are a lot), so I’m really coming to this screenplay quite ignorant. Which, in the end, might be to my advantage.

On its own, this is a wonderful and energetic screenplay written by Greta Gerwig. It brims with wit and intelligence, and it’s abundantly clear that this was a passion project for the writer. Every line, every page, every word feels infused with care and love. When it comes to screenplays, such feelings are rare. Screenplays are not meant to be literary but this one has a literary air about it.

What is Little Women about?

This is the story about the four March sisters— Jo, Amy, Meg, and Beth— and their life during the American Civil War. Each of them harbor artistic gifts- Jo is a writer, Amy is a painter, Meg is an actress, and Beth is a pianist- and the sisters share a tight bond. They befriend their orphaned neighbor, Theodore Laurence (or Laurie), inviting him to participate in their childhood games, squabble with each other as siblings are wont to, and they grow up.

That might be reductive (and I apologize!) but it’s really quite wonderful. As with the novel, the screenplay is divided between the events of their childhood and their new lives as young adults; unlike the book, the screenplay switches back and forth between the timelines, connected by thematic or emotional moments. It is easy to imagine Gerwig finding kinship with Jo’s ambitions as a writer working to be taken seriously. And she wanted to honor this in some way, a sort of “collapsing of Louisa May Alcott, the author and Jo March, who was her avatar in some ways. And to make a movie that answered... the legacy of what Little Women had done, from the first time it was published in 1868”. Gerwig, in wanting to recreate the experience of revisiting one’s childhood, adds that past memories often tend to be “messier and stranger and spikier than... the collective memory of it is.”

It examines the role of women in the world— especially in the 19th century when their options for prosperity were near-zero unless they got married. These are themes that were present in the book (or so I hear); Gerwig extracts them and infuses her own personality and style through them to create a period piece that manages to be contemporary without being anachronistic. Take, for instance, this example on page 40, School Girl #2 talks about how the Marches benefited from the Civil War:

It’s a small moment but one that feels like the script is having a conversation with Alcott’s work.

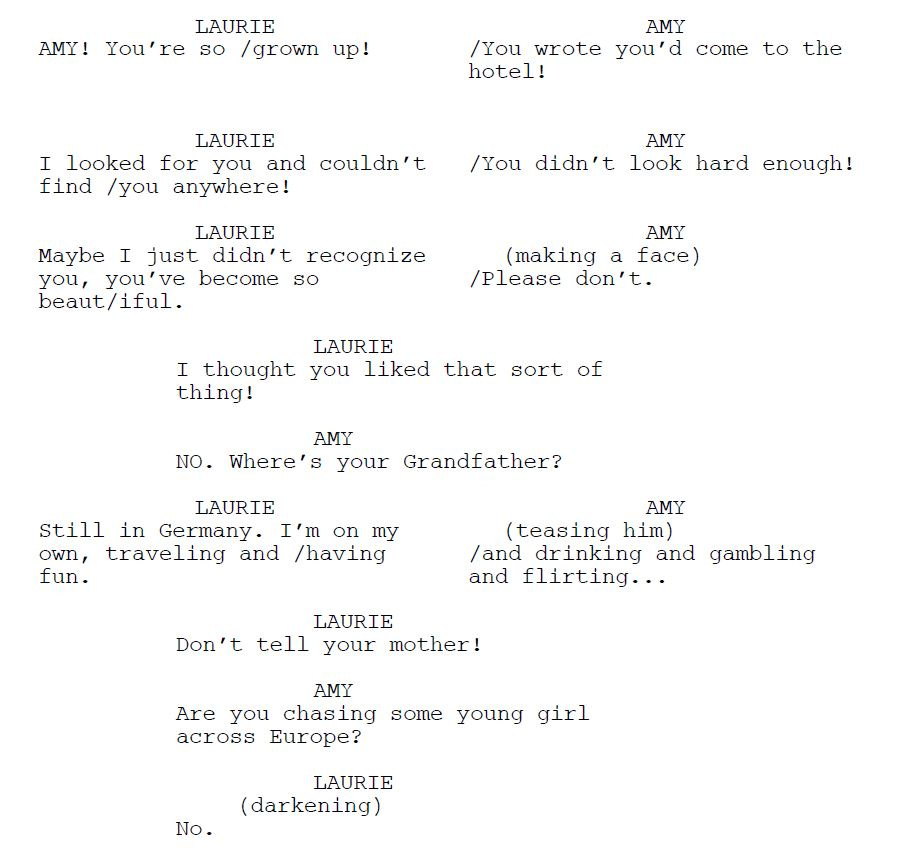

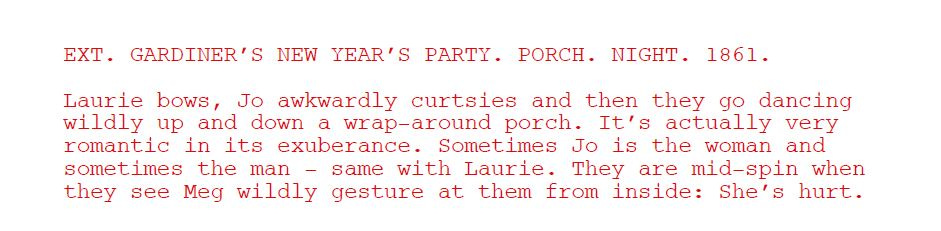

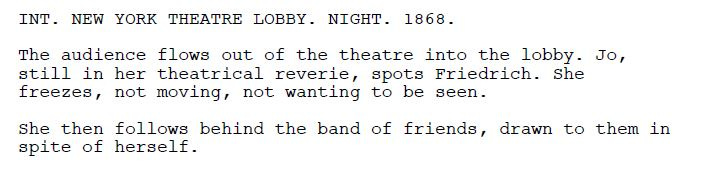

One of the wonderful things about Gerwig’s adaptation is the rhythm of the dialogue. Given that the March household is a rambunctious sort where the sisters talk fast, talk over each other or at the same time, Gerwig writes the verbal exchanges to reflect that, using a slash ‘/’ in the middle of dialogue represents at which point the next speaker’s dialogue should begin, helping to keep time of the dialogue’s rhythm. In an interview, Gerwig explains that the ‘/’ is a device commonly used by playwrights, less so in screenplays. “But I knew I wanted these very famous lines… to just come out with so much speed and so much energy and physicality that… it’s embodied,” she says. “I had written it with this very specific overlap so you could hear everything but that it was this cacophony of sound, this controlled chaos.”

For anyone interested in writing this kind of dialogue, Little Women represents a refreshing break from the usual suspects famous for their dialogue (i.e. Aaron Sorkin, Quentin Tarantino, David Mamet). There really is a musicality to the way it’s structured, and it’s also littered with instances of dual dialogue, which doesn’t always make an appearance anymore.

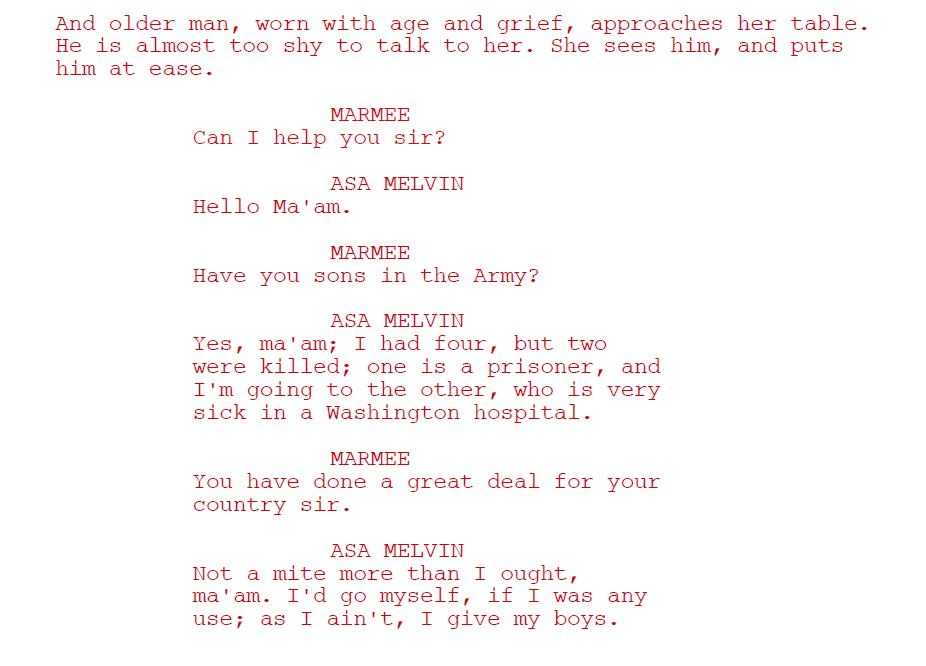

When Gerwig took on the project, she was hot off the acclaim for Lady Bird (#16 on the WGA’s List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century) for which she’d received Oscar nominations in the Best Director and Best Original Screenplay categories. For Little Women, she’d receive a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. Although she’d written before, Lady Bird and Little Women were her first efforts at writing and directing her work on her own (Hannah Takes The Stairs and Nights and Weekends were made with Joe Swanberg, while Frances Ha and Mistress America were collaborations with Noah Baumbach). Given her acting background, it makes sense that she’d bring that sensibility to crafting roles for actors that were rich, complex, and attractive. In Little Women, every character brims with a life and story arc of their own, allowing even for minor characters to make the most of their time, such as this old gent on page 73.

How does Greta Gerwig write? In her own words, she says she tends to overwrite. “And then I tried to find the architectural structure of what it is I’m going for. I don’t predetermine the structure. I gather all my materials, which is this page count really, and then I see where the structure is, and then I try to start weaving it all together. I start bringing it together and it is very tactile.”

Her approach is closer to that of a literary writer than a scriptwriter who focuses on structure; in a way, it brings to mind Stephen King’s approach to writing in which he writes and then tries to sort it out. If you want to write like this, by all means; however, if you are pressed for time, you may want to give it some thought before mimicking Gerwig.

Another interesting fact: Gerwig draws from a lot of references for her projects, not just when she’s making the film, but in her writing. For Little Women, Gerwig didn’t restrict herself to the book only, but lifted inspirations and even dialogue from Louisa May Alcott’s private letters, her later novels, and even scholarship on the author’s life, thus helping to enrich the script before it even hits the shooting stage. For instance, this memorable piece of dialogue on page 100 was actually borrowed from Alcott’s 1876 novel “Rose in Bloom,” about a young woman who goes to live with seven male cousins and clashes with them:

The final line, “But I’m so lonely,” is Gerwig’s own invention.

The lesson being: Draw from anything and everything in the writing process; even if it’s an adaptation, there’s no rule to say you must be confined within the boundaries of the text.

What is Greta Gerwig's writing style?

At the start of the story, Gerwig makes some notes and gives the reader a few keys to help make sense of what they are about to read, particularly with the timelines:

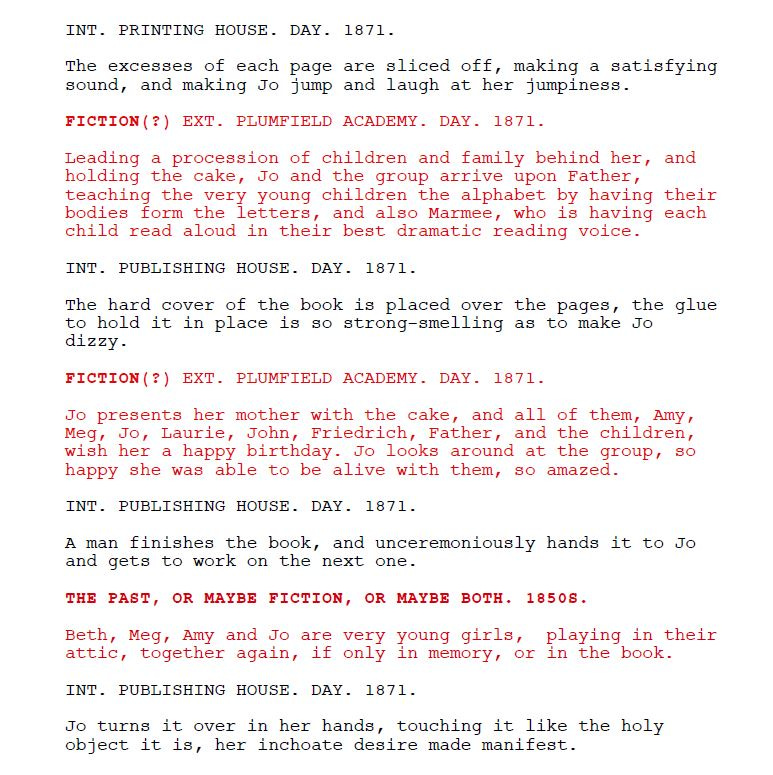

Gerwig uses RED FONT COLOR for all scenes set in the past and BLACK FONT COLOR for the scenes in the present- this helps to avoid confusing the reader as to which point in the timeline a particular scene is taking place.

Finally, all timelines move forward from their origin point- meaning there won’t be flashbacks WITHIN the Past scenes or the PRESENT scenes.

Other examples:-

How Greta Gerwig writes a montage:

How Greta Gerwig writes a scene with action:

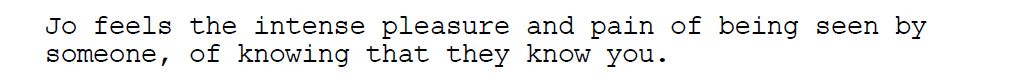

How Greta Gerwig writes a setting:

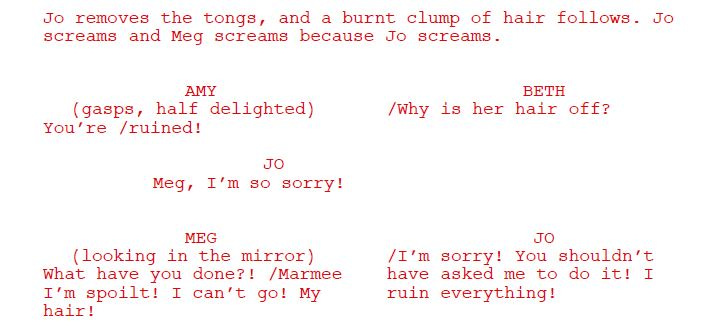

How Greta Gerwig writes a reaction:

That being said, Gerwig also adds “THE PAST” or “THE PRESENT” before every scene heading to indicate when a transition is made, eliminating any ambiguity… at first, this seems redundant because the font color should indicate when the scene is taking place- until you arrive at the final two pages, and the scenes in red have “FICTION (?)” prefacing the scene heading instead of “THE PAST”, asking the reader to decide whether or not this is the ending that we would like, for it also takes place in 1871, the same as the present).

She also uses a lot of directions in her parentheses, yet they don’t distract from the flow; on the contrary, they enhance it and offer actors more clues on how they should feel about their character and act in the given scene.

This is a rich screenplay. I don’t know how it compares to past adaptations, but to me, Gerwig’s take feels definitive. It’s clearly a labor of love that honors the text but leaves room open for the writer to smuggle in her views, perspectives, and style that enhances what is there. The result is a fantastic screenplay that offers much to learn from, and makes for a fascinating read on its own.