The Incredibles (2004) Script Review | #48 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A fun and exciting riff on the superhero genre that still remains captivating two decades after its release.

Logline: Bob Parr has given up his superhero days to log in time as an insurance adjuster and raise his three children with his formerly heroic wife in suburbia. But when he receives a mysterious assignment, it’s time to get back into costume and save the world.

Written by: Brad Bird

Pages: 129

Some circles on the Internet believe that The Incredibles is the best Fantastic Four movie that was never made (not including the upcoming Marvel Studios’ film). It’s hard to disagree with the sentiment. From the first page, Brad Bird’s screenplay takes off and never looks back. Here is a superhero story that is highly entertaining, packed with memorable characters, and quite personal. That last ingredient tends to be missing in most superhero stories put on screen.

The premise is surprisingly simple. Fifteen years after the government outlawed superheroes, former hero Bob Parr/Mr. Incredible is unable to resist accepting an assignment from a mysterious client that requires getting back in costume. Too bad that the client is a supervillain called Syndrome who holds a personal grudge against Bob! Now it’s up to Mr. Incredible to stop Syndrome before he destroys the city and wipes out all superheroes. But to do that, he’s going to need the help of his family.

The other Parrs:

Helen Parr/Elastigirl – Bob’s wife, super-stretching powers;

Violet Parr – 14-year-old daughter, invisibility powers;

Dash Parr – 10-year-old son, super-speed powers;

Jack-Jack – the baby, multiple powers.

The first half of the screenplay focuses largely on Bob Parr and his yearning for the former glory days. Stuck in a job he hates, disconnected from Helen and the family, the assignment allows him to reconnect with himself—and in turn, with the family. The montage on page 51 is both touching and an excellent example of how to write a montage— instead of breaking it down shot-by-shot, capture the essence of what the scene accomplishes:

Now compare that with the finished scene:

It says nothing about how Bob gets back in shape (turning the railyard into his personal gym is one of my favorite touches) or how he reconnects with Bob and the children, yet the gist of it is there, written down in three paragraphs.

After Syndrome makes his entry proper by the Midpoint on page 61, the second half of the script expands the roles of Helen, Violet, and Dash as they go to Syndrome’s island to find Bob. After Helen, Violet, and Dash get their own individual heroic moments—Helen sneaking into the compound, Violet and Dash taking out guards that come after them—the family is reunited properly on page 101, which is when the story becomes a proper ensemble.

It’s worth noting that the adults get more priority because they have deeper stakes—Bob jeopardizes his marriage and family in pursuit of reliving the past; Helen worries that her husband is cheating on her and that she will lose him. But Bird’s genius lies in also giving the children—and even Jack-Jack— mini-arcs and their own smaller goals to pursue. Violet learns to overcome her insecurity and master her powers, which also boosts her confidence and attracts the attention of the boy she likes. Dash is granted permission to take the leash off his powers and uses it well on the field. Jack-Jack… well, Jack-Jack has an entertaining moment where it turns out he does have powers—multiple powers—that come in handy in taking down Syndrome in the end. In the sequel, those powers become a focal plot point.

Bird’s choice of powers for the Parrs was not random. They are tied into archetypes that add to the personalities of the characters. Since the father of a family is meant to be strong, Bob was given super strength; a mother gets pulled in all directions, thus Helen has the gift of super-stretching; a teenage girl would rather hide from the world than show what she can do, so Violet gets powers of invisibility and force fields; and since 10-year-old boys tend to be hyperactive balls of energy, Dash got super speed. Even Jack-Jack’s multiple powers allude to the notion that babies, being blank slates, have infinite potential. The powers give each character an additional personality trait. In an ensemble, that is crucial because it makes each character stand out.

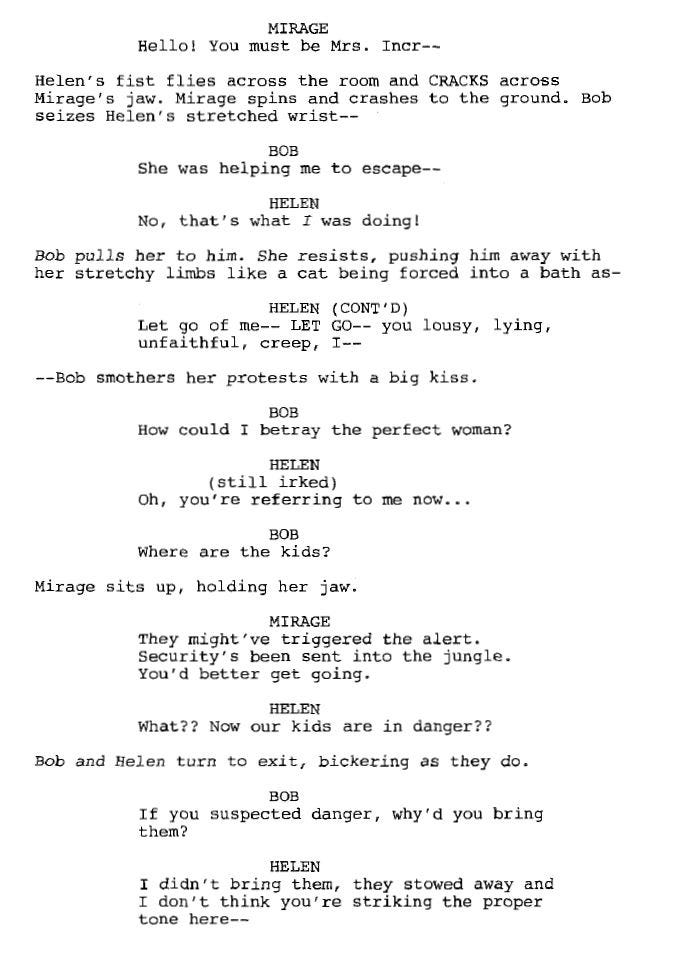

But powers alone don’t make a story. The Incredibles balances the mundane with the fantastical, grappling with real issues that affect people. Bob and Helen have arguments like any married couple, even in the middle of life-and-death situations, such as on page 95…

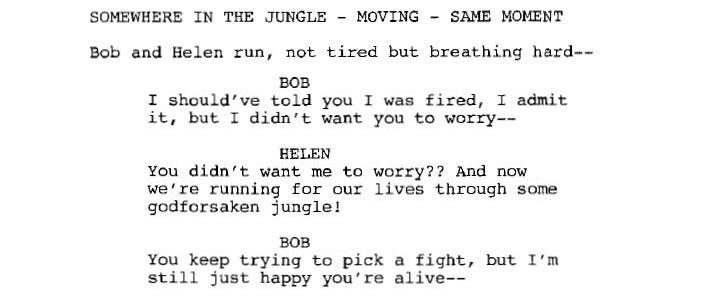

… and page 99…

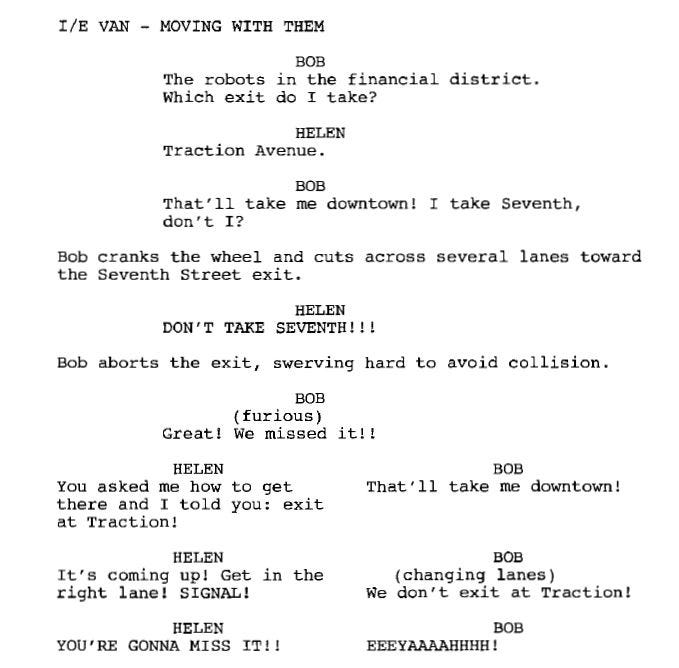

… and again on page 110…

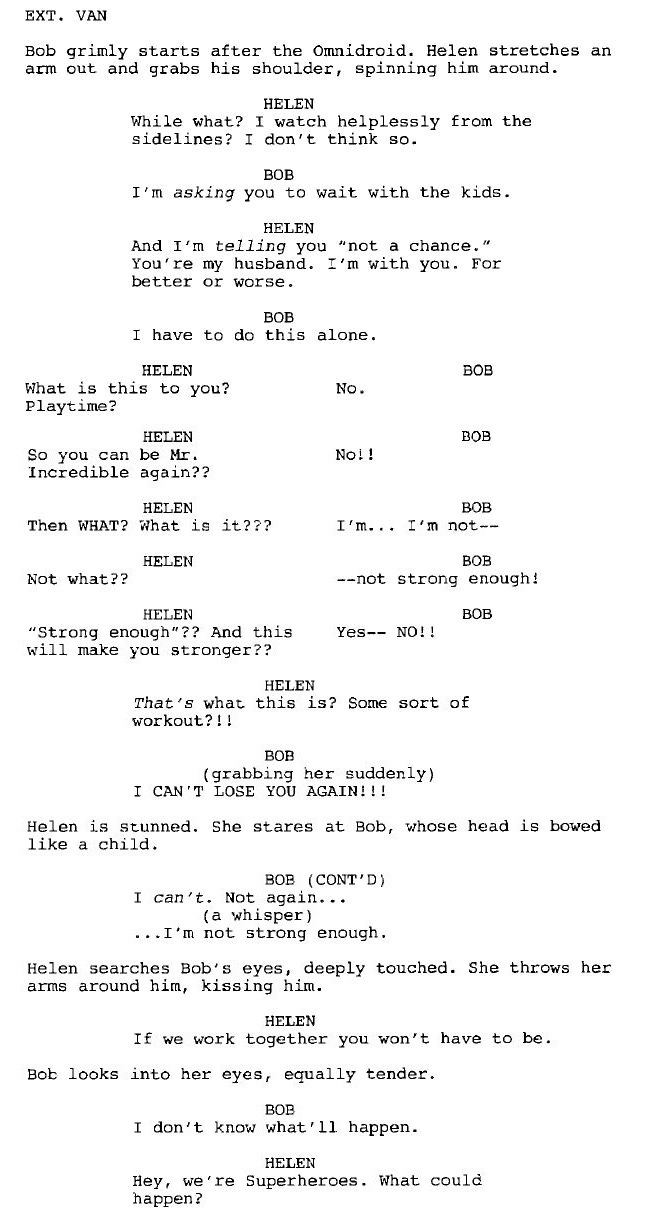

Which is why when it culminates in Mr. Incredible’s confession on pages 111-112 right before the big fight, it feels real.

You don’t have to have superpowers to have experienced such arguments, whether it’s in your own marriage or in witnessing other couples (including your parents). Many superhero stories spend so much time on elaborate set pieces or unnecessarily complicated plots that they forget to develop the human drama that connects with the audience.

Incidentally, in creating this fictional universe, Bird avoids excessive detail and keeps description to a minimum. This allows scenes to be trim, and to move quickly. For instance, look at how Bird writes a rapid series of shots on page 3.

Or the scene in which Dash lets loose with his powers for the first time to evade the enemy.

To establish the world of The Incredibles, Bird begins the screenplay using a device that he’d later use in Ratatouille: the interview. This technique introduces us to Bob, Helen, and Frozone, a superhero with ice powers and Bob’s best friend, when they were in their prime. It also sets up the themes of the constant need to save the world and the idea of retiring or not (ironically, Bob muses in the interview on the possibility of settling down while Helen rejects the notion of retiring— in reality, the opposite happens). In 1.5 pages, Bird gives us the main characters, establishes the ideas that the screenplay will explore, and launches us into a universe where superheroes exist.

The concept came to Bird as early as 1993. Like Bob, Bird was a bit stuck in life, and was beginning to wonder whether his career goals were attainable only at the price of his family. The unfortunate bomb of his excellent debut animated feature, The Iron Giant, did not help matters except in prompting Bird to move to Pixar after pitching the concept of The Incredibles to John Lasseter, whom he knew. Early versions of the story had a different villain altogether— a baddie named Xerek who happened to be Helen’s obsessed ex-boyfriend in the mold of a James Bond villain. Syndrome would have only appeared in a minor role as a villain who discovered Mr Incredible’s identity and attacked the couple at the beginning of the movie. But his popularity with the film’s crew led to revamping the story to make Syndrome the primary villain. The rest, as they say, is history.

To distinguish this world from other superhero fare, Bird drew on spy films, television show, and comics that he read growing up. Perhaps in a surprising reveal, Bird’s knowledge of the superhero genre is quite limited, stating in an interview:

“I was not a big comic-book reader. I read a few, when I was little, but I was really much more into things like "Peanuts" and "B.C."—funny strips. I got my heroes second-hand, from television and movies, to a certain extent. When fans ask if I was influenced by issue 47 of Whoeverman, I have no idea what they're talking about. I'm perfectly willing to believe that I'm not the first to come up with certain ideas involving superheroes; it's probably the most well-trod turf on the planet. If there are similarities, it's simply because the same thoughts that occurred to other people also occurred to me. I'd be astonished if anyone could come up with any truly original powers that were at all interesting anymore.”

In a separate interview, Bird elaborates on the myriad of influences he drew from to create The Incredibles:

“Consciously, I’d always thought of The Incredibles as a tribute to the pop mythology of my youth, a gumbo of spy movies, comic books, and favorite television shows; but I realize now that the other half of its ingredients came out of personal anxieties about family, work, expectations, and the special gifts we are all given but don’t always appreciate.”

The psychologist Carl Rogers wrote, “What is most personal is most universal.” Martin Scorsese would later elaborate on this to say, “The most personal is the most creative.” I think this is why The Incredibles has succeeded and remained a favorite in the Pixar filmography (especially in contrast to hits like Toy Story 3, Finding Nemo, and WALL-E) and the superhero genre. Bird uses the trappings of the story to address issues and worries that weighed on his mind. In the process, he created a highly riveting and entertaining script that earned him his first Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay nomination. Got problems? Turn it into art. It’s not a bad way to deal with an existential crisis.