Ratatouille (2007) Script Review | #95 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Equally heartwarming, mature and thrilling, Ratatouille goes the distance and then some in a script that is kid-friendly, yet offers plenty for adults to love.

Logline: Remy dreams of becoming a great French chef despite his family's wishes— and because he’s a rat! But when Remy crosses paths with the hapless garbage boy Alfredo Linguini at a famous Parisian restaurant, he discovers an opportunity to team up with Linguini and show off his culinary skills, as the pair soon turn the culinary world of Paris upside down.

Screenplay by: Brad Bird

Story by: Jan Pinkava, Jim Capobianco, Brad Bird

Pages: 116

Pixar has seven entries on the WGA’s Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century; six of them were penned between 2000 and 2010. I’d argue that Ratatouille, despite being ranked lowest on the list, is the best of them. Here is an outlandish premise turned into a beautiful paean about dreams, acceptance, and what it means to be an artist. Although Pixar has always made family-friendly fare, Ratatouille contains some of the most adult themes, characters, and plot development.

Remy the rat has a highly developed sense of smell and a love of food, two gifts that nobody in his family truly appreciates. When circumstances cause him to wind up in Paris and inside the fine dining restaurant of his idol, Chef Gusteau, Remy finds an opportunity to fulfill his dream of cooking by teaming up with a hapless but kind young garbage boy, Alfred Linguini, who gets credited for Remy’s abilities instead.

Ratatouille defies easy categorization. It’s a workplace comedy, because it takes place inside the high-pressure environment of a fine dining kitchen run by a nasty little man, Chef Skinner, who has taken over the establishment since Gusteau’s death. But it’s also a buddy comedy, considering Remy and Linguini’s partnership. It’s also a family drama, as Remy’s father, Django, loves his younger son but struggles to accept that he will always be a different kind of rat; there’s also the paternal connection in which Linguini is discovered to be Gusteau’s illegitimate son and must struggle in the second half of the script to live up to his father’s legacy as the new restaurant owner (doubly difficult since he has zero cooking abilities).

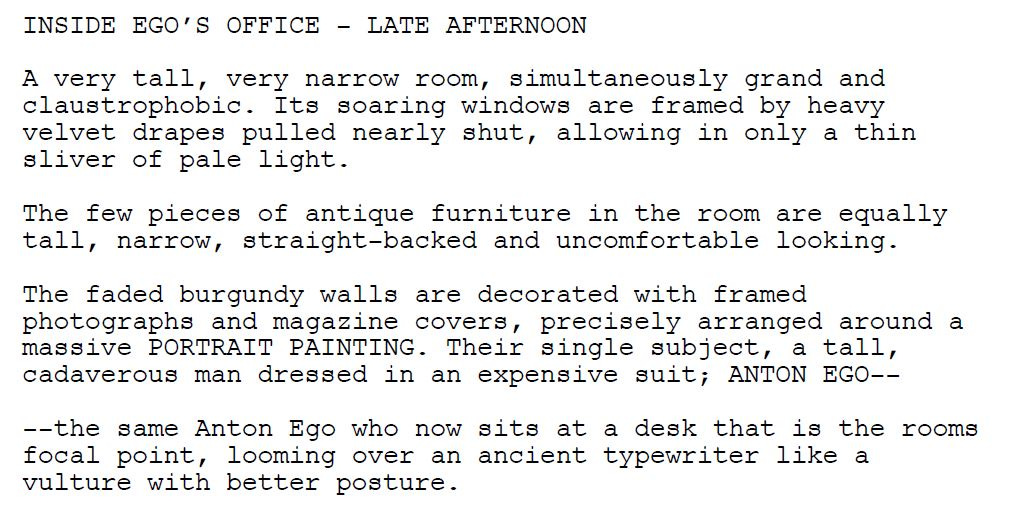

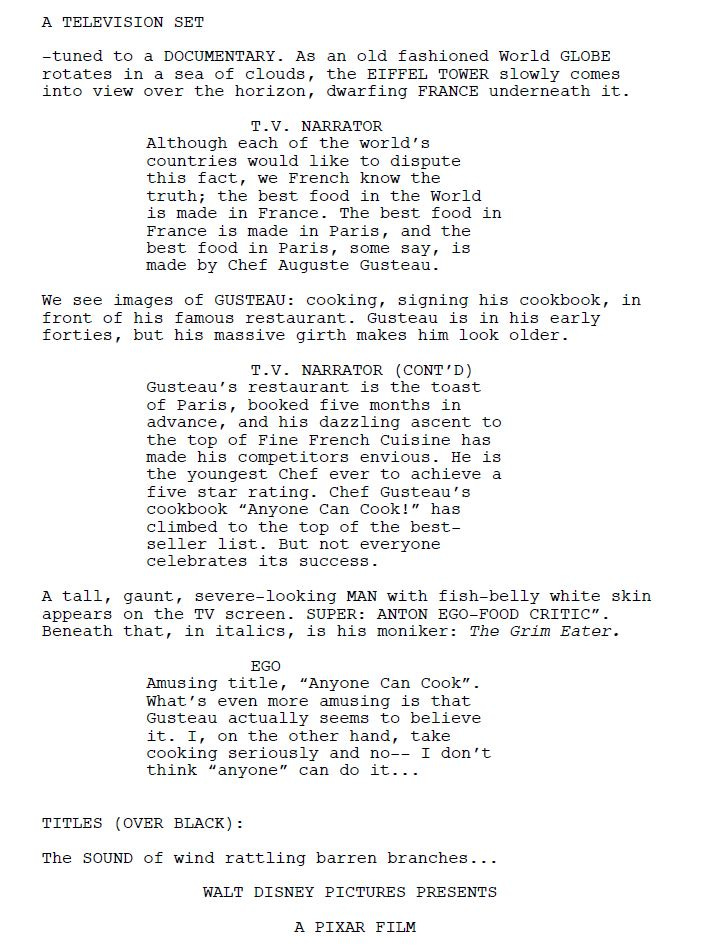

It all comes to a head in a showdown that would make Sergio Leone proud: Remy must deliver a dish that wins over the skeptical and terrifying food critic, Anton Ego, while Skinner tries to sabotage their efforts by kidnapping Remy on the same night, all without the assistance of the kitchen staff who leave upon learning the truth (except Colette, who returns to help them). And it’s here that the screenplay truly reaches great heights: Instead of “defeating” Ego in a traditional sense, the critic is bowled over by Remy’s ratatouille dish and in his endorsement of Gusteau’s, he delivers a powerful and stirring monologue about the nature of criticism and artists that feels like Moses coming down from Mount Sinai with the stone tablets. It forces the reader to change their view about Ego— he loves food and the ratatouille dish reminds him of this; by the end, he is an ally and supporter of Remy, Linguini, and Colette by investing into their new bistro. In doing so, Ego feels like a three-dimensional complex character. You know: human.

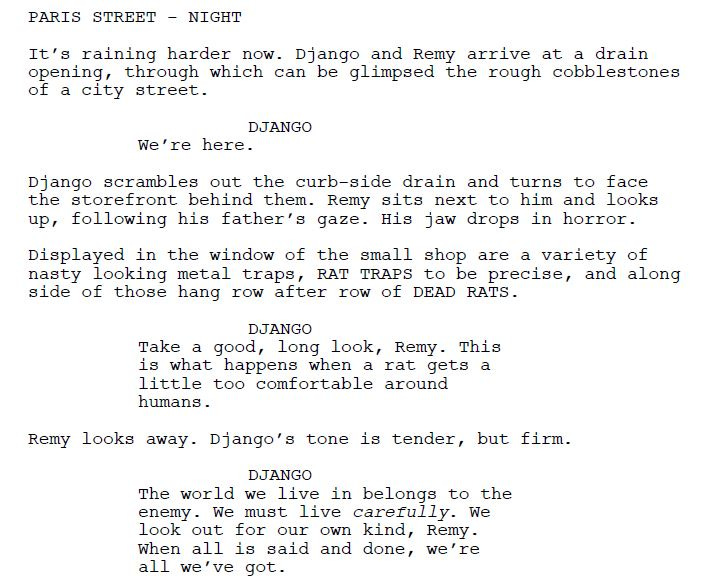

The same applies to Django. He clashes with Remy not out of spite, but because he fears that his son’s naivety will get him killed. He shows Remy a pest controller window display of dead rats (page 68) to warn him that rats and humans cannot co-exist, a fact that is reinforced by how most of the world reacts to Remy.

But in the end, Django is won over by Remy’s courage and Linguini’s act of protection against the rest of the kitchen, and accepts his son as he is (page 106-107). It’s a touching moment made better by resisting a conventional heart-to-heart speech and hugs and “I love you” exchanges. Instead, Django shows his love by volunteering the clan to help him run the kitchen on that crucial night.

In contrast, Skinner remains the true antagonist. He tries to cash in on Gusteau’s image by starting a line of frozen food products, then tries to sabotage Linguini and Remy after he is ousted. In the end, he does “defeat” the duo by outing their secret and getting Gusteau’s shutdown, but it is a pyrrhic victory because the new bistro allows Remy to openly indulge in his love of food, turns Ego into a pleasanter person, and lets Linguini do what he does best- serve people.

Ratatouille was a problem child, and nearly fell apart. Jan Pinkava, who directed the Oscar-winning short Geri’s Game, came up with the concept in 2000, and created many of the original design, sets, characters and core storyline. Unfortunately, the story development seemed to have hit a wall and in 2005, Pinkava departed Pixar. The company brought in Brad Bird, fresh off The Incredibles, to replace him. Bird only had 18 months to meet the release date instead of the usual three years. Undaunted, he got to work and started by making three crucial changes to the script that made it stronger while retaining its originality:

He killed off Chef Gusteau and reduced his role to that of a figment of Remy’s imagination, choosing to give prominence to Chef Skinner as the antagonist.

He maintained focus on Remy’s storyline by cutting out most of Remy’s family- more brothers and sisters, a mother, an uncle- and separating them, only to bring them back at the most inopportune moment (when Remy is just experiencing success).

He expanded the role of Colette— then largely a background character with a few lines— to add more complications after discovering that female chefs face an uphill battle in the kitchen. Plus, the relationship helps to deepen the story.

For Bird, it was critical to emphasize on how believable the situation was (after all, it’s about a rat who aspires to become a chef!). Mark Andrews, story supervisor, said, “It doesn't have to be logical because there's no way a rat is going to pull your hair and make you do things. There's no way a rat is going to cook. But you can believe if somebody was as sensitive as Linguini, you can pull that off. So there were those scenes where we had to see a kind of progression of that idea”. In addition, Bird recognized that the Cyrano de Bergerac-like situation opened many opportunities for physical comedy as Remy learns to operate Linguini like a puppet in the kitchen.

Ratatouille is proof that if you want to create a world that draws people in, you should do research. Bird and a small team flew to Paris for six days to get a feel for the authenticity of Paris, while producer Brad Lewis interned for Chef Thomas Keller at his French Laundry kitchen to get a feel for how French kitchens worked (Keller would create the ‘confit byaldi’ version of the ratatouille that Remy serves critic Anton Ego in the climax). Just as Tolkien makes you believe in a world of Hobbits by stressing the small details, you believe you are catching a glimpse of what it’s like to be inside a fine dining kitchen.

How does Brad Bird write screenplays?

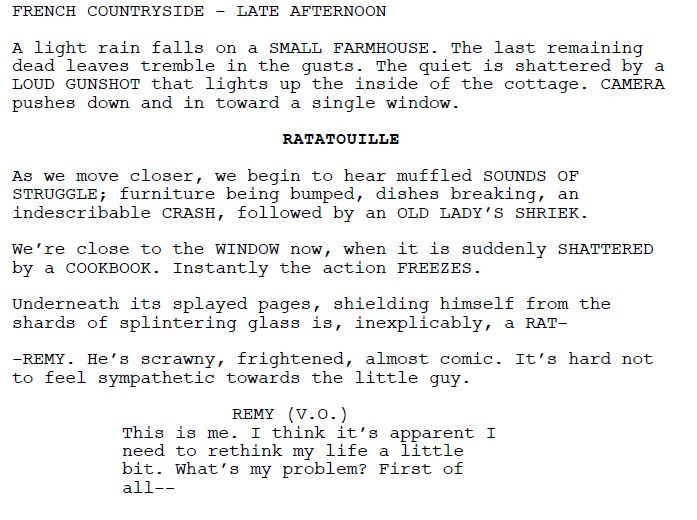

Bird has an interesting way of scripting screenplays. For starters, he doesn’t use ‘INT.’ or ‘EXT.’ for his scene headings, which is uncommon, yet still works because we can immediately understand where the scene is taking place. He also tends to capitalize his character names throughout the script instead of following the convention of capitalizing it only the one time (Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Phillipa Boyens did the same when adapting The Lord of the Rings).

Moreover, he opens the script with a faux-documentary that accomplishes the following: It establishes the setting (Paris, France), what it’s going to be about (cooking and fine dining), the main arena (Chef Gusteau’s restaurant), the ‘Big Bad’ (Anton Ego), and the theme (anyone can cook). He did something similar previously on The Incredibles, using an interview to introduce us to the heroes in that world. Here, the documentary lasts less than one page, killing multiple birds in one go. When in doubt, use this framing device to orient readers

Some caution against using “We” when writing action lines. But Bird is liberal in the use of ‘We’ to guide our eye towards the action unfolding, and hey, if it was nominated for an Oscar, you can use it too.

Ratatouille is the perfect blueprint for learning how to write concise and effective montages as the script is packed with them. Consider the montage on page 40 in which Remy and Linguini practice to work together using their newly discovered system: The entire montage is three short paragraphs— whereas the scene in the film lasts a little over 2 minutes. But on the page, most of the gags (for example, accidentally squeezing a tomato, and sending a saucepan flying through the window) are omitted. But the essence and core objective of the montage is clearly stated: “By dawn, Linguini and Remy have meshed into one finely honed cooking machine.”

The lesson: As long as the key objective of the montage is explicit and clear, you don’t have to describe your montage in minute detail. Brevity is your friend for writing montages succinctly.

Notes:

Holzer, Leo N. (June 29, 2007) Pixar Cooks Up A Story | The Reporter

Collura, Scott & Moro, Eric Edit Bay Visit: Ratatouille

Finz, Stacy (June 28, 2007) For its new film 'Ratatouille,' Pixar explored our obsession with cuisine