The Farewell (2019) Script Review | #91 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Lulu Wang turns her autobiographically-inspired story into a powerful screenplay that captures the complex dynamics of family and the struggle to reconcile different cultural identities.

Logline: Billi, a headstrong Chinese-American woman returns to China when her beloved grandmother is given a terminal diagnosis, and struggles with her family's decision to keep grandma in the dark about her own illness as they all stage an impromptu wedding to see grandma one last time.

Written by: Lulu Wang

Pages: 89

Cultural differences are an excellent source to mine for comedy and drama. Clashes between views, opinions, and even languages create authentic conflict and a sense of specificity; to quote James Joyce, “In the particular is contained the universal.”

At its heart, The Farewell concerns itself with universal troubles- conflict with family, familial love, the specter of death hanging over a loved one, and feeling lost. But its premise is certainly particular as a family stages a wedding in order to spend time with the elder matriarch instead of telling her that she has cancer.

The Farewell is a part of a recent trend in American productions that focus on the stories of non-Americans (or Americans of different origins) where a large chunk takes place outside America, is based on the writer’s real-life experiences and, more often than not, told by women (other examples: The Souvenir, The Souvenir Part II, Past Lives, Aftersun). Over 70% of the dialogue in The Farewell is Chinese Mandarin and set in Changchuan, China.

But I digress.

The screenplay, written by Lulu Wang, is a case study in how to turn what could have been an excess of contrived situations and forced comedy into a deeply affecting portrayal of how each person in the family copes with the fact that someone they know has been handed a medical death sentence, and choose to hide it from the sentenced.

The central source of conflict and tension comes from the protagonist, Billi Wang. Unlike her parents, Haiyan and Jian, or her Uncle Haiban, Billi has a worldview that hews closer to American. She loves her grandmother, Nai Nai, and thinks that she ought to be told about her condition. But Nai Nai’s sister, Little Nai Nai, chooses to hide the diagnosis and the rest of the family plays along. To avoid any suspicion over all of them suddenly turning up on Nai Nai’s doorstep, they pretend that Billi’s cousin, Hao Hao, is getting married. The poor boy has only been dating the girl for three months, and suddenly, she’s been pulled into this scheme. If they realize they aren’t compatible, do they stay together for the sake of Nai Nai’s happiness? And where are the girl’s parents? Is the wedding even legal or was it all a show?

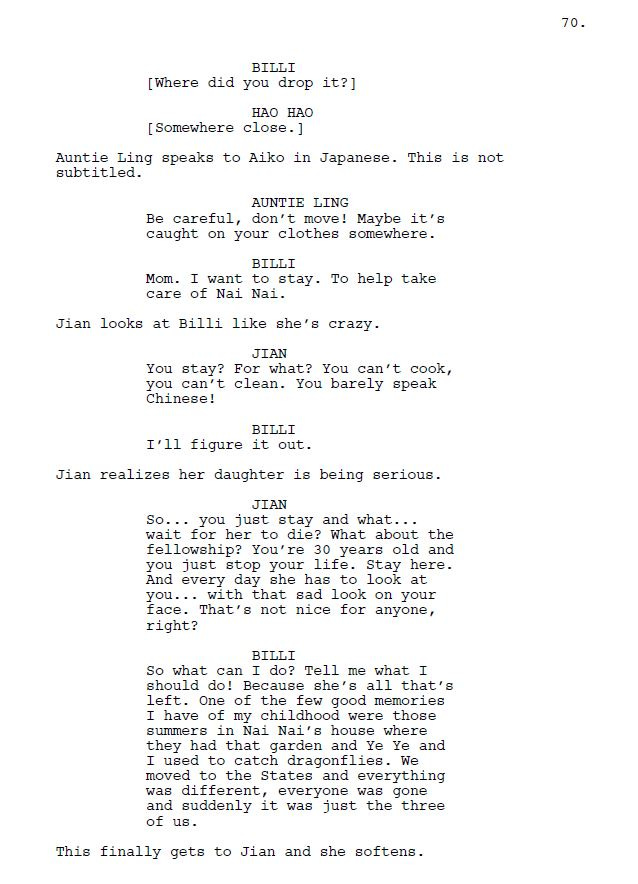

Wisely, the script doesn’t dive into those rabbit holes, and is all the better for it. The focus remains on Billi and her family enjoying every moment they have with Nai Nai, while Billi also grapples with feelings that surface with her return to China after so many years. The feelings of leaving her homeland and being an immigrant while not knowing when she will see her beloved grandmother again culminates in a tearful and moving monologue on pages 70-71.

Lulu Wang (born February 25, 1983) is a Chinese-born American filmmaker. She studied music and literature at Boston College, graduating in 2005 with a double major in literature and music. Some of her early work included short ‘day in the life’ videos for legal firms to depict the daily struggles injured victims faced in mundane activities. Her love for filmmaking overtook initial plans to become a concert pianist; in 2008, she moved to Los Angeles and co-founded Flying Box Productions alongside Bernadette Bürgi. After making multiple web shorts and music videos, she wrote and directed her first feature, Posthumous.

Wang wanted to make her second feature about a real-life incident that took place in her family, which is the genesis for The Farewell. But raising the money was extremely difficult- financiers wanted her to make changes and whitewash characters to make it more commercially appealing, and it wasn’t only the Americans; a Chinese producer made it clear in no uncertain terms that they needed a white guy in the story. Wang refused, but decided she needed to tackle this in a different way. She wrote and narrated the story as an episode called ‘What You Don’t Know’ for This American Life, the radio show hosted by Ira Glass. The ploy worked: The episode caught the attention of producer Chris Weitz, and piece by piece, The Farewell came together as Wang envisioned it, and without a white guy in sight.

Nor does the story need it. The Americanized Billi automatically fulfills this role, allowing the reader to orient themselves through her point of view. The shifts are subtle, as Billi comes to understand that the family’s deception is a way to carry the emotional burden on behalf of Nai Nai instead of placing it on her shoulders (page 69). For any non-American writers reading this, the takeaway is that you don’t always need a token white person to tell a story with a cast of non-white people.

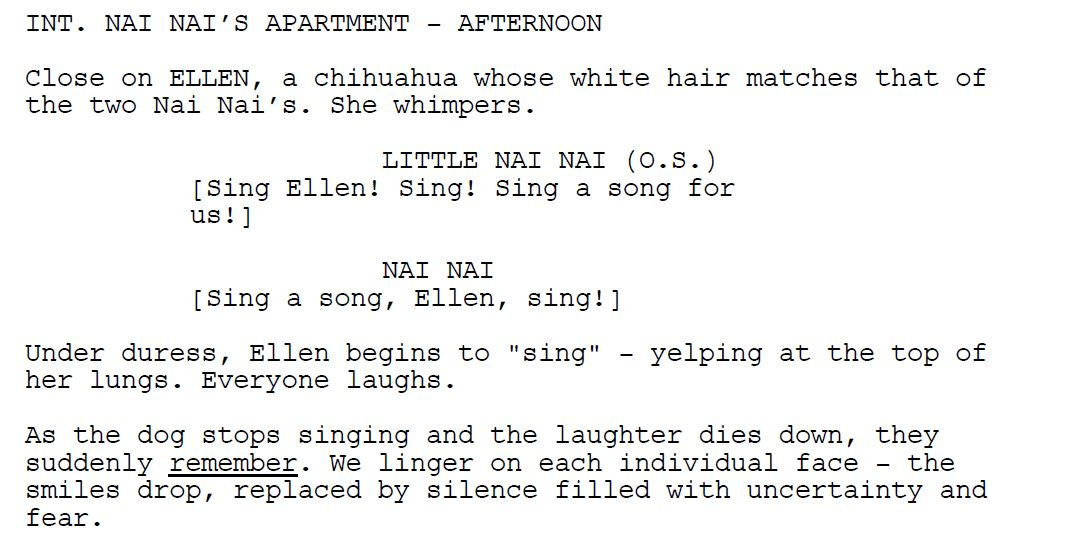

But what about the dialogue? How do you write a screenplay where most of the dialogue is in a non-English language? Wang’s solution is so deceptively simple that, I confess, I wanted to slap my forehead for not having realized this sooner. The entire thing is written in English, and the Chinese Mandarin dialogue is placed between square brackets, as demonstrated below:

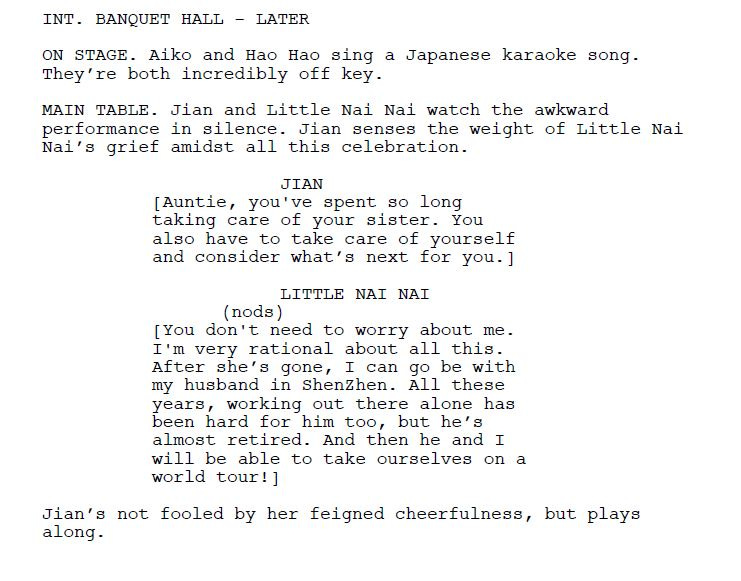

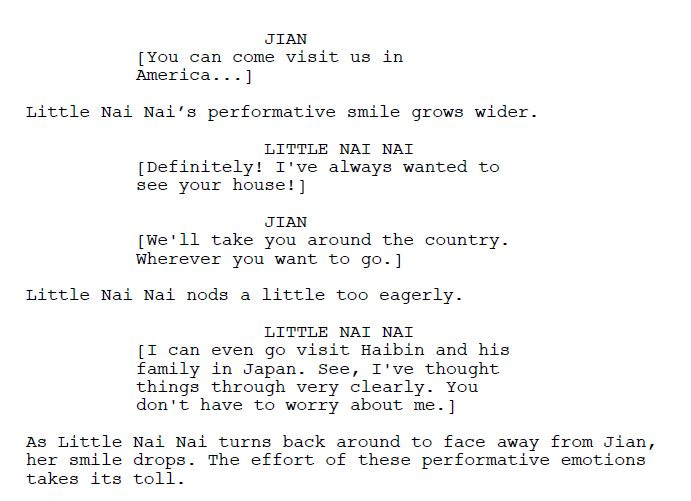

No matter the language, however, the rules of storytelling still apply, and The Farewell is no different. As mentioned earlier, tension is generated by ensuring that Nai Nai doesn’t cotton on to the family’s ruse. But in choosing not to stretch this out to exaggerated lengths (as some comedies are guilty of doing), plenty of space opens up for Wang to insert scenes that explore the environment or allow characters to share a moment of humanity. The family goes to a massage parlor, they visit Ye Ye’s grave (Nai Nai’s late husband), and Ye Ye himself makes an unspoken appearance as a ghost looking over Billi. At the wedding, Billi and Haiyan perform a karaoke number, Jian and Little Nai Nai have a conversation about what the latter will do after Nai Nai dies…

… and Billi and her shy cousin share a brief wordless moment in support of each other.

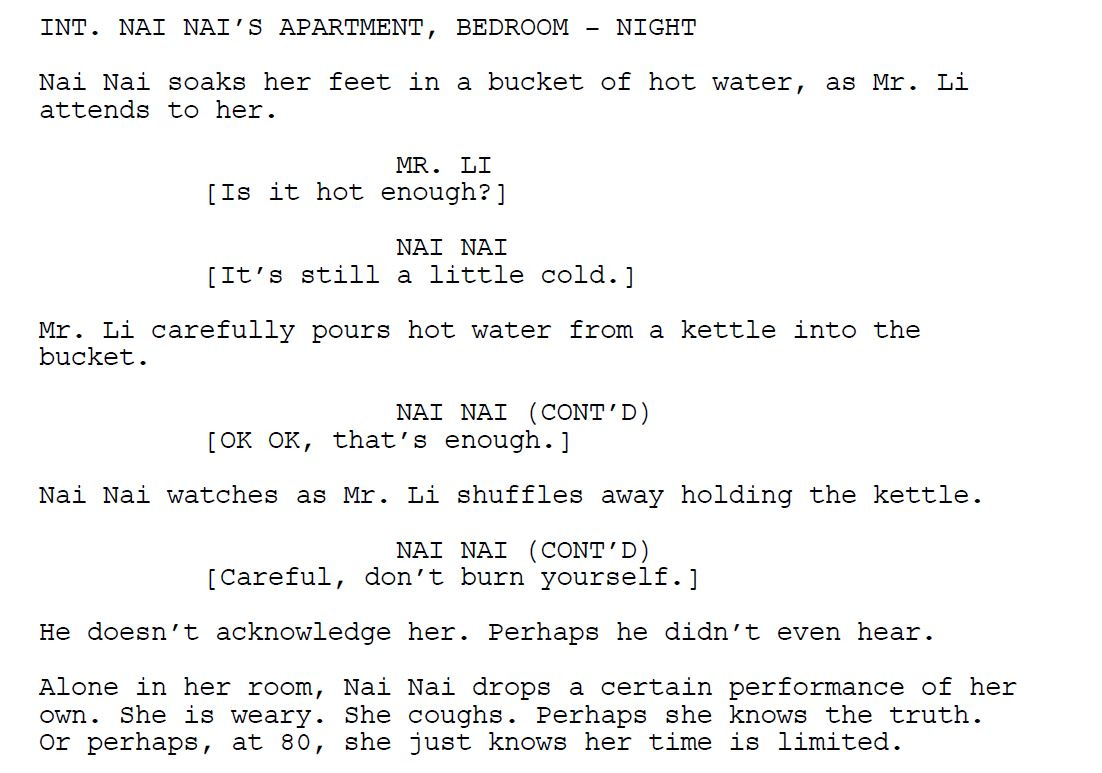

These are the best parts of the screenplay, especially one moment on page 69 where Nai Nai finally has a moment to herself and doesn’t have to perform.

These snapshots are golden nuggets of truth and humanity; they elevate The Farewell beyond its clever concept into a work of art. Even though it’s restrained, these moments allow for a certain style to shine through, not unlike the stillness found in the works of Yasujiro Ozu or Hayao Miyazaki. Sometimes, they even allow for humor to come through.

The Farewell is the first entry on this list (counting backwards) that is set in another part of the world and does not contain a lot of English (and no, Borat does not count!). It’s an excellent example on how to write a story that does not hew to traditional American dramatic fare; where being different can get you ahead. Moreover, if you can’t raise the money you need to write this kind of screenplay, Wang’s strategy is equally worth emulating: Find a different, inexpensive way to tell it so that it generates the interest needed in the first place to get it made.

Notes:

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/585/in-defense-of-ignorance/act-one-5

https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/the-farewell-lulu-wang-interview-a24-1202158932/