Sideways (2004) Script Review | #15 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A charming and affectionate script about two middle-aged men, their disappointments, the women in their lives, and wine.

Logline: Two men reaching middle age with not much to show but disappointment embark on a weekend-long trip through California’s wine country, just as one is about to take a trip down the aisle.

Written by: Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor

Based on: “Sideways” by Rex Pickett

Pages: 142

Sideways is a poignant examination of what it’s like to reach middle age with little to show for it, told in a wry and amusing fashion. Here’s a screenplay that tackles real human problems and fears, though rooted in outlandish escapades that verges on disbelief, topped off with a heady dose of knowledge about wine.

The premise is relatively simple. Two friends take a week-long trip through Californian wine country in lieu of a one-night bachelor party. The trip is the brainchild of English high school teacher, Miles; the soon-to-be married man is an actor, Jack. Both men use the trip to deal with their private troubles. Miles is anxious about selling a novel he recently completed; Jack worries that his acting career is going nowhere and solves his anxieties over his upcoming nuptials by deciding to sleep around before settling down with Christine. Over the course of the week, plenty happens. Miles finds the courage and timing to act on a crush he has on a waitress, Maya; Jack gets it on with a single-parent named Stephanie, and even contemplates calling off the wedding. Things happen along the way, good and bad, and the two friends— and Maya and Stephanie— drink plenty of wine.

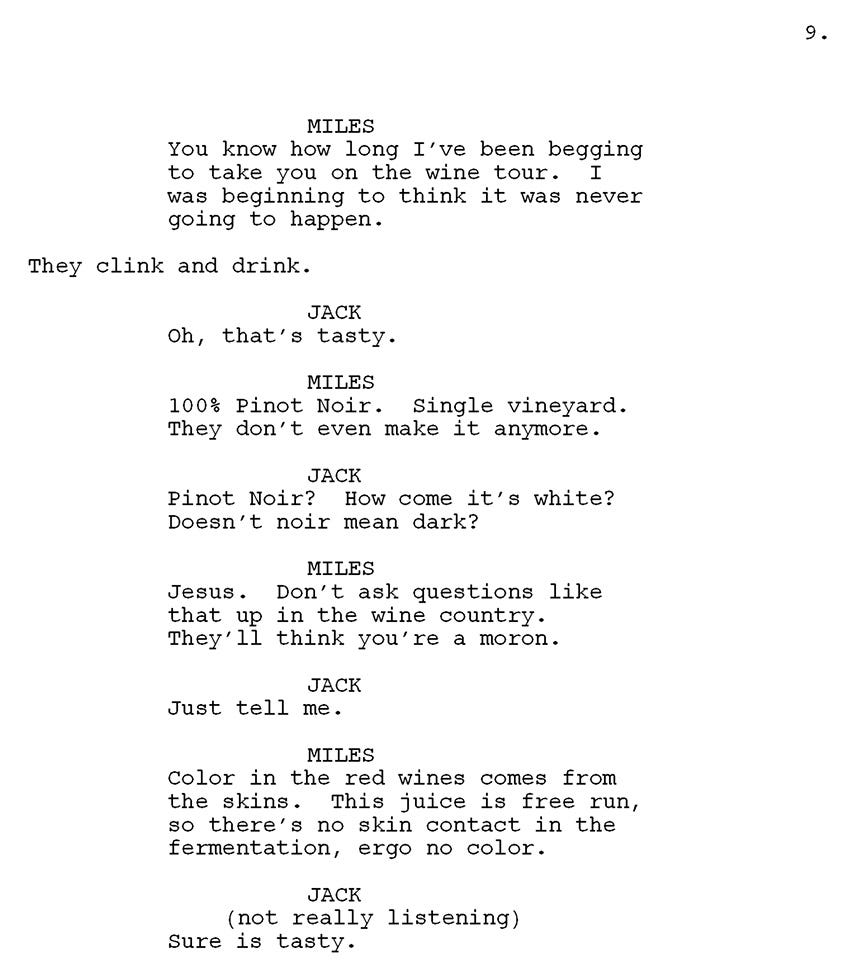

That’s the second time I’ve mentioned the wine, so let’s talk about it for a moment. It’s hard to cite another script in which a character shows off his knowledge about a subject in as much detail as Sideways does about wine. It’s not superficial, either—it really gets in to it.

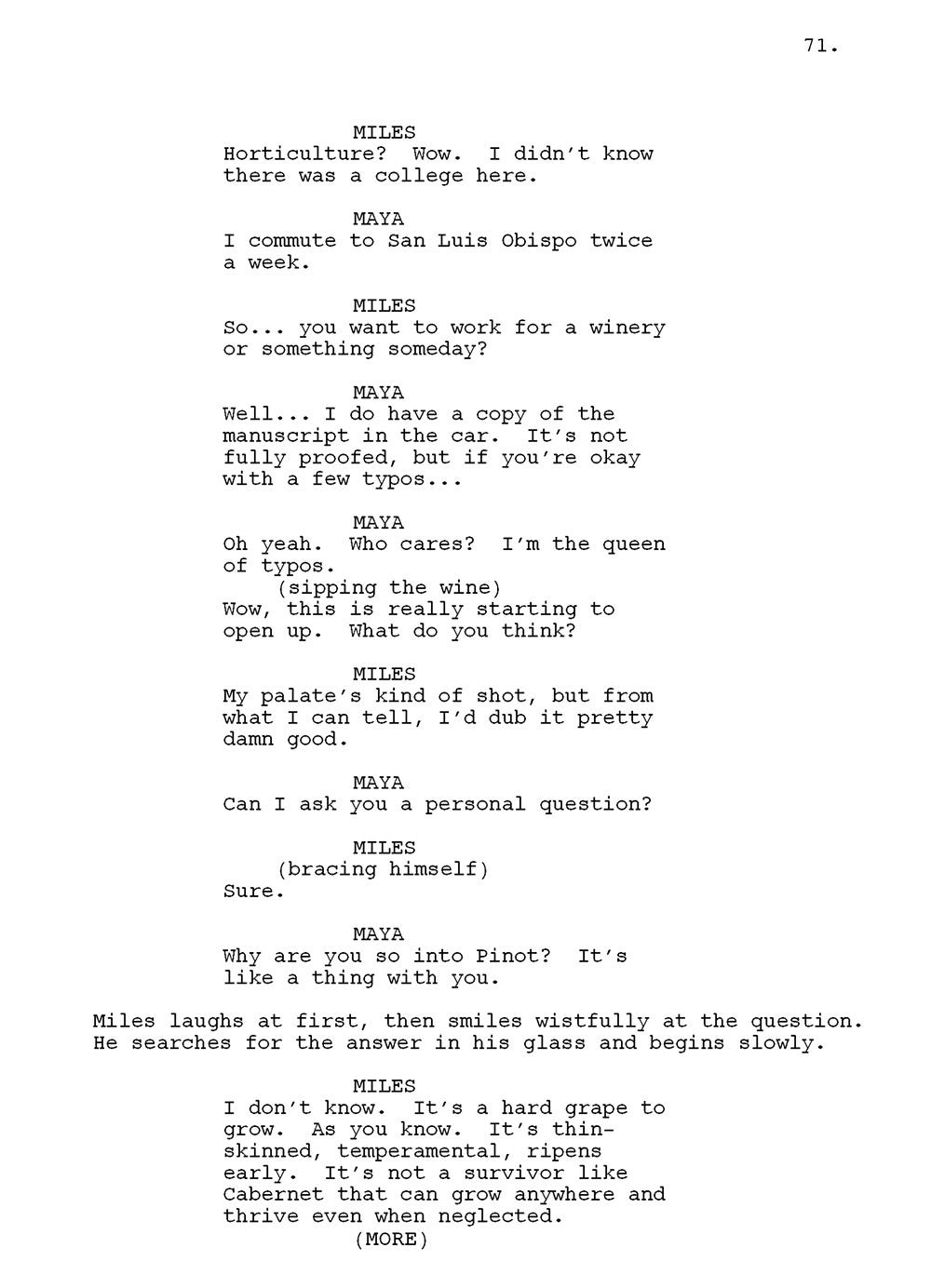

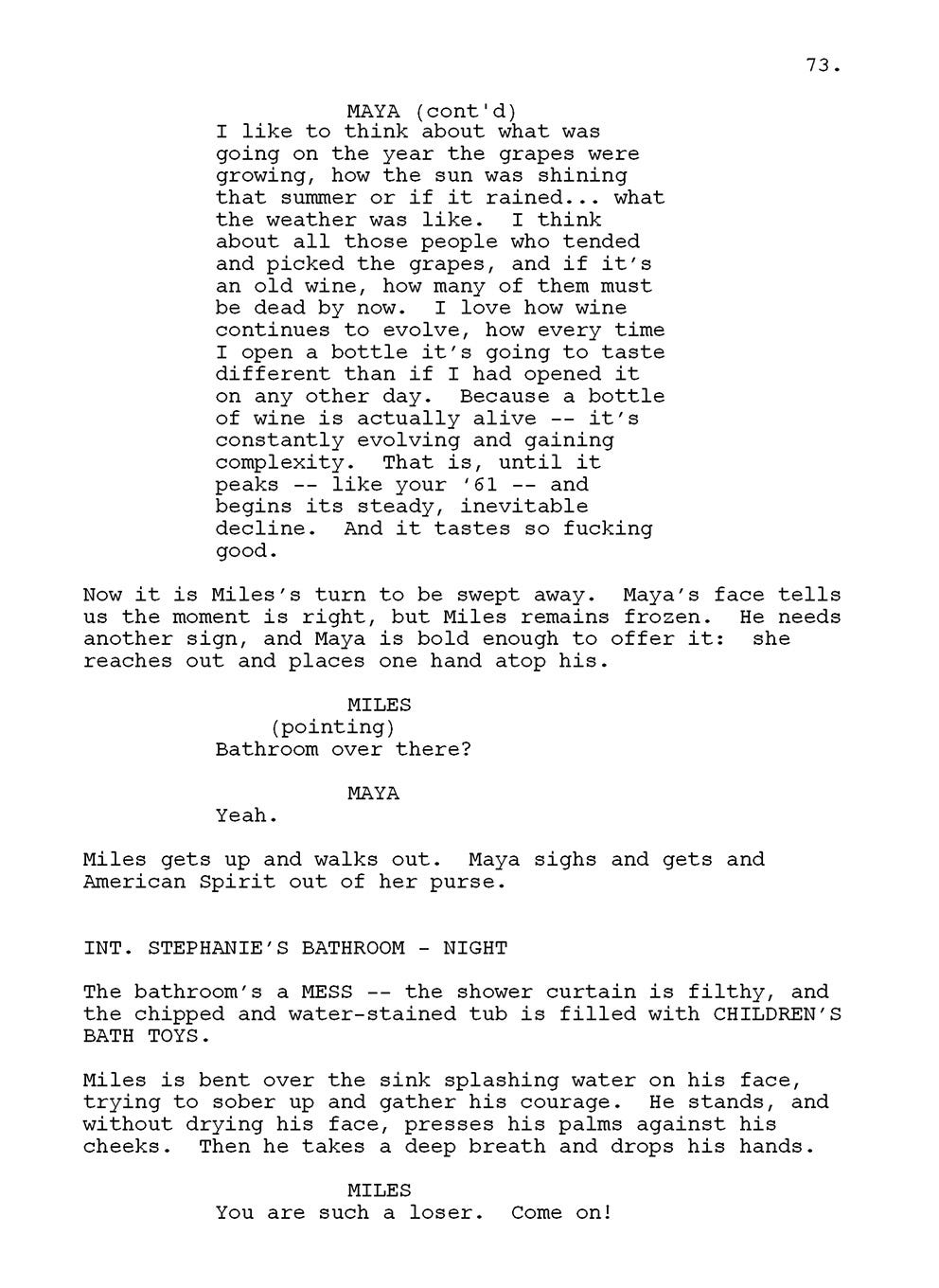

However, it works because the wine ties directly into Miles’ personality; and to a degree, that of Maya. In one of the most sublime and poetic exchanges in the script, the topic of wine turns into subtext about the characters. For instance, when Miles shares why he loves talking about pinot noir so much, he’s really talking about himself; when Maya talks about what she thinks when she drinks wine, she’s revealing her intelligence, sensitivity, and imagination. Wine, as a subject, is a storytelling device to show character and bring us into a world not often seen.

Jack, on the other hand, is the driving force of the story— gregarious, larger than life, and charming. If Miles is the superego, then Jack is the id. Despite their opposite personalities, there is genuine consideration underlying their friendship, especially from Jack’s side…

… even if it comes out in unusual ways—like wanting to help Miles get with Maya on the trip while he’s, uh, also getting it on.

Sideways is what Blake Snyder refers to as a ‘Buddy Love’ story. But it’s an atypical one at that because so much is happening around Miles and Jack. For instance, there’s the story arc with Miles still not over his ex-wife, Victoria, as well as finding the possibility of new love with Maya. There’s Jack and Stephanie’s dalliance, and whether or not it will derail the wedding. It all collides together, although the scenes with the ladies predominantly takes place during Act 2, while Act 1 and Act 3 focuses on Miles and Jack.

If Sideways feels unconventional, that’s because it is entrenched in personal and human experience, courtesy of author Rex Pickett. The history behind the story makes visible the source of its rich personality. Pickett drew on his own life for the character of Miles, while Jack was inspired by a good friend, Roy Gittens. Sometime in 1996, Pickett invited Gittens on one of his soon-to-be regular trips in Santa Barbara to play golf. Around that same time, Pickett was really getting into wine. Given the lengthy distance, these trips would be overnight stays. On these sojourns, Pickett would stay at The Windmill and eat at a restaurant called The Hitching Post—where Miles and Jack would sleep and dine at respectively! He’d also gravitate to the pinot noir that The Hitching Post made— Miles likes pinot, too!— and it was there that he met a gorgeous waitress named Renee, who undoubtedly inspired the character of Maya.

Gittens suggested that Pickett turn these experiences into a script. Encouraged by his friend’s belief, Pickett cobbled a script together in about three weeks—and hated it. Frustrated, he impulsively wrote a short story told from Miles’ point-of-view; and something clicked. Inspired, Pickett decided to turn his screenplay into a novel, and plotted out the beginning and the end. He also made a decision thereon to tell it all from Miles’ perspective. His agent loved the manuscript, as did the film’s future producer, Michael London; the publishers and Hollywood did not. Sideways, it would seem, was dead on arrival.

Somehow, the manuscript found its way to David Lonner’s table. Lonner was an agent working at Endeavor at the time. More importantly, he represented director Alexander Payne, an up-and-coming talent in film circles. The journey from Lonner to Payne and ultimately to screen is a different story altogether, but a series of several near-misses and another five years later, Sideways made it to the big screen. In an ironic twist, the novel was not published until five months before the film hit theaters, and even then only in paperback.

Pickett was struck by the script that Payne wrote with Jim Taylor; mostly, he was struck by their faithfulness to the material. This included all scenes being seen from Miles’ point-of-view, and retaining the day structure used in the novel. Later, Payne would praise it as the easiest adaptation he’d done at the time: “It read like a screenplay,” he said.

If you lay out the structure and break it down, it looks like this:

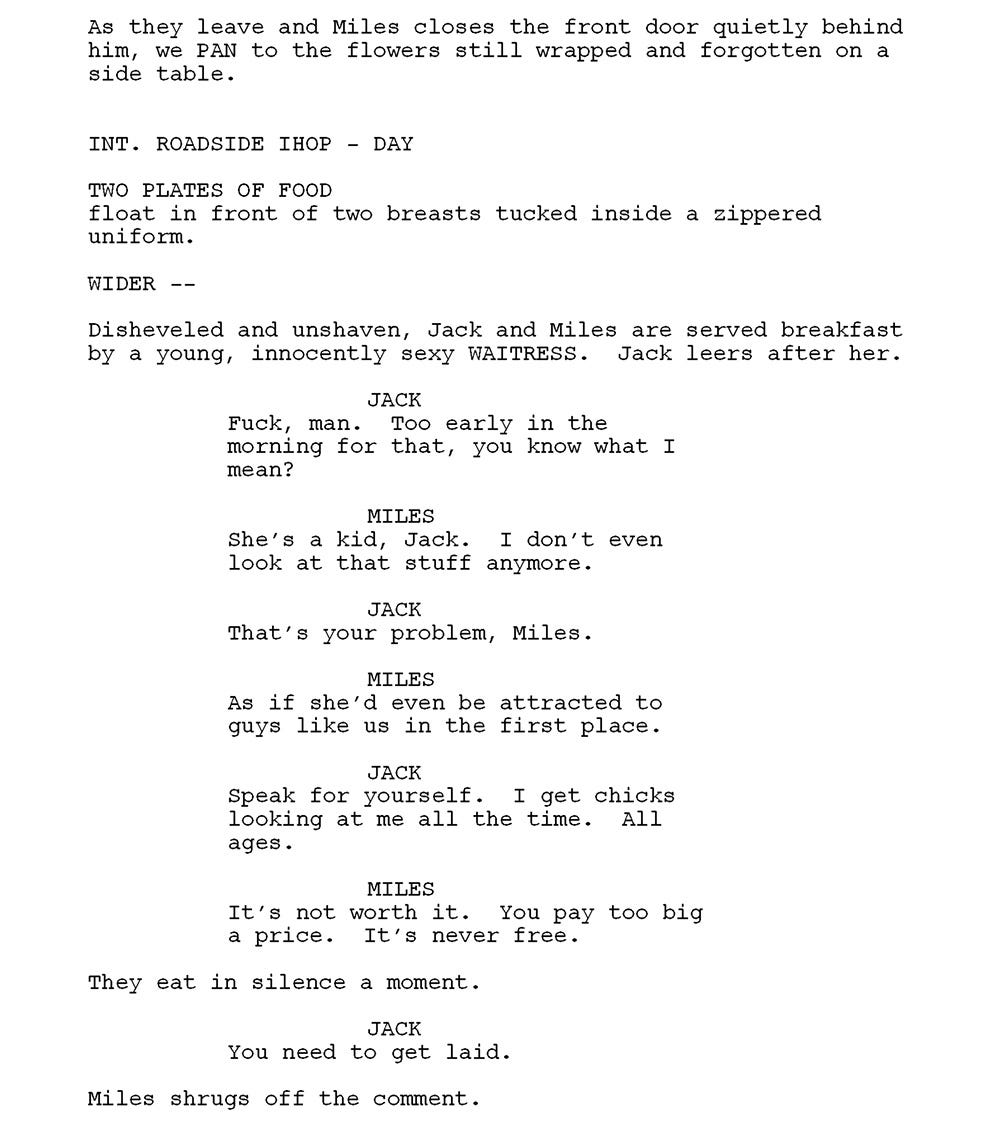

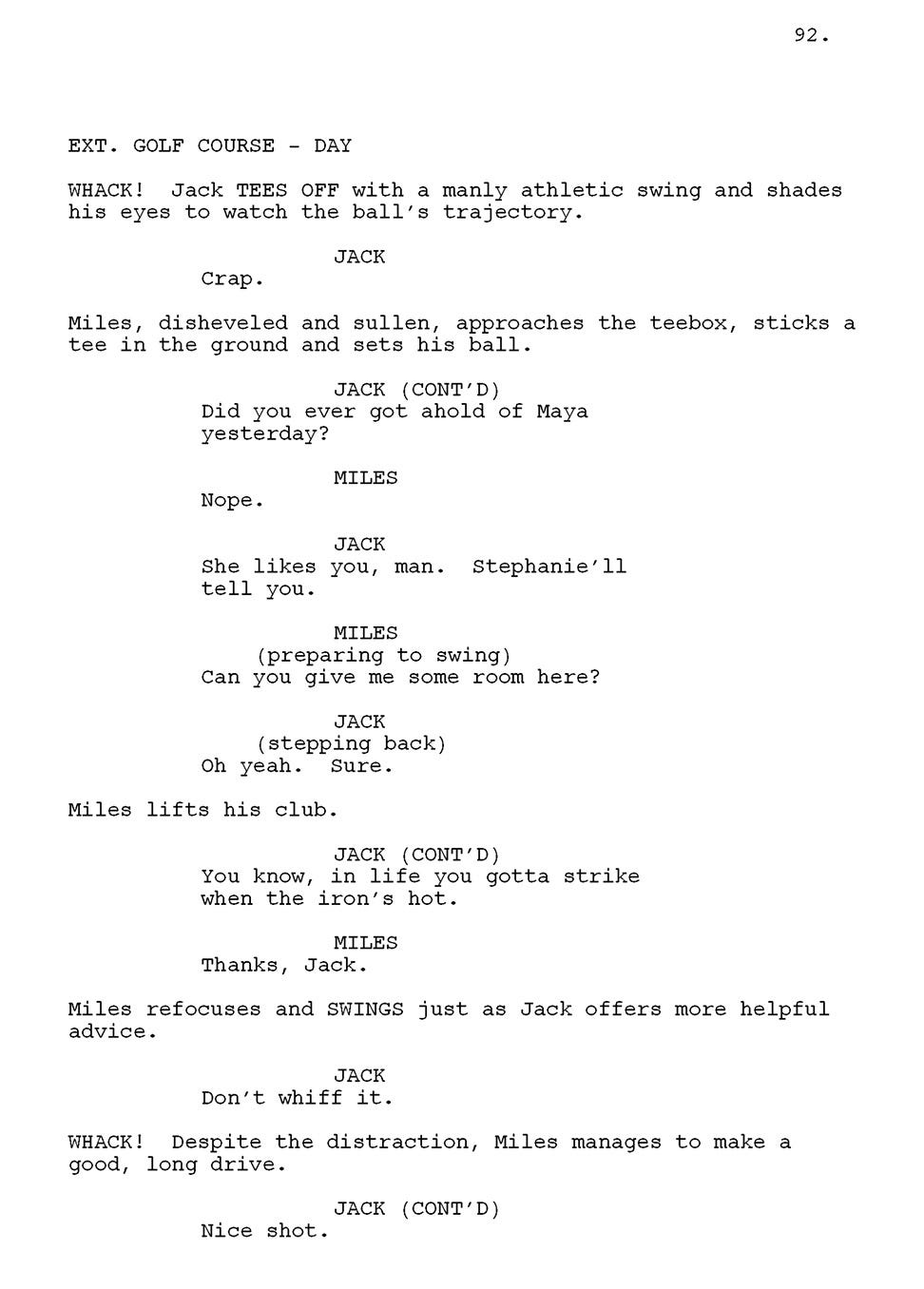

The writing is absolutely fabulous. Payne and Taylor, who wrote the script on spec, lifted dialogue and scenes from the novel. However, look at the way they write certain shots to make it cinematic without using camera directions…

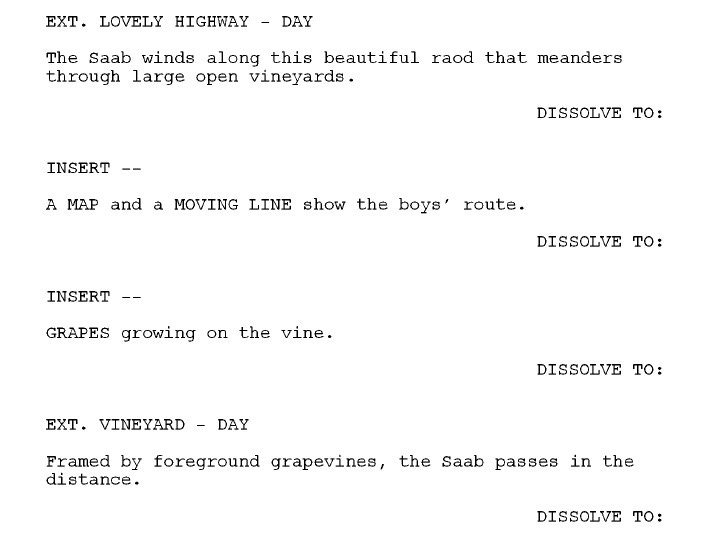

Or how they condense a journey into a few lines…

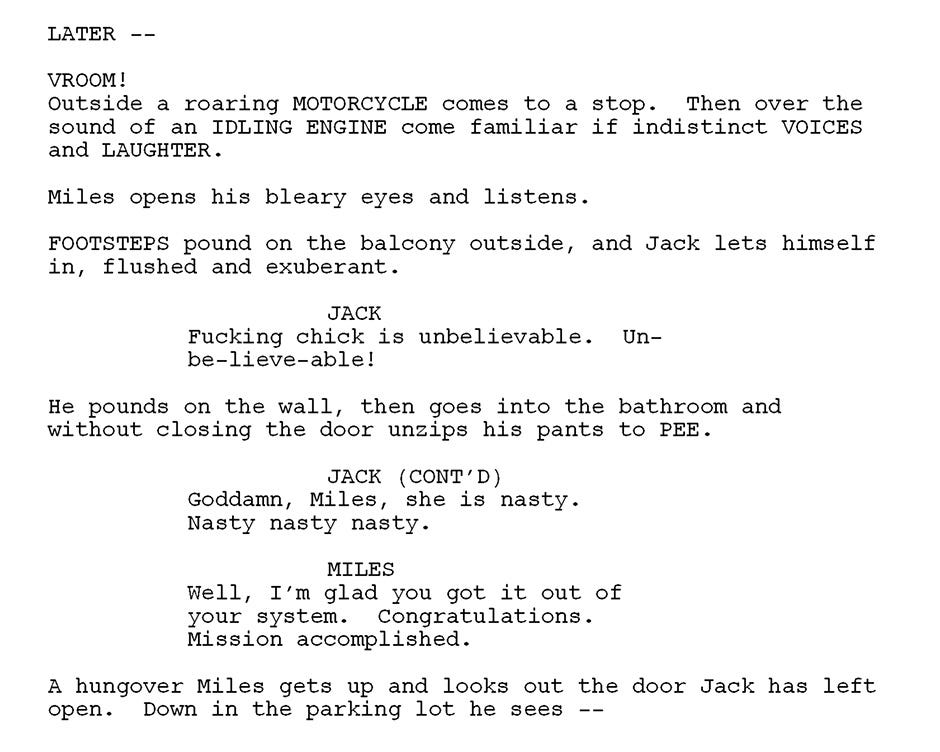

Look further at how onomatopoeia is cleverly used to engage the senses…

… making it feel like we can hear the scenes…

And how comedic turns of phrases are used, such as to describe Jack and Stephanie having sex…

I also love how they write a montage to show Miles and Maya getting closer on their first double-date dinner…

Moreover, there is rhythm in the dialogue; the comedy is organic; and the vulnerability is really affecting. The novelistic quality of the writing, too, is no doubt inspired by the source material.

In a bold move, the script’s third Act adds one more shenanigan between the women breaking things off with the men and the wedding— Jack learning his lesson about infidelity the hard way. It’s a sequence that could easily risk dragging down the story. Yet somehow, it actually turns into a moment of humbling Jack and allowing Miles to have a hero moment when he darts into the waitress’ house and grabs Jack’s wallet while she and her husband are in the middle of sex. By the time the wedding happens, it’s a brief moment, and not as important to the rest of the story; it wraps up quickly without overstaying its welcome.

(Note: two scenes in the script were filmed but ultimately left out—the one where Miles hits a dog that later is found dead (to symbolize Miles’ low state at that point in the narrative) and another where Miles buy shoes.)

The writers also amended the original ending of the script (in the book, Maya turns up to Jack’s wedding reception and leaves with Miles), in which Maya’s voicemail abruptly cut off and Miles is left stumped. Pickett was a bit disappointed with the added scene of Miles going to see Maya but it was a halfway compromise, and one that works out much better in my opinion.

Sideways1 remains timeless. Its flawed protagonists and their relatable dilemmas turn the story into a deeply affecting story. Payne and Taylor deservedly won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, for it still packs a punch. Pickett must be singled out, though, for writing the story in the first place— he really took the advice, ‘write what you know,’ and turned it into something uniquely memorable.

Notes:

Ross, Matthews (2004) | IN VINO VERITAS (Filmmaker Magazine)

Ryfle, Steve (February 5, 2016) | A Look Back on Sideways (Creative Screenwriting)

StoryMapsDan (June 19, 2012) | Rex Pickett interview (Sideways, Vertical) (Act Four Screenplays)

Pickett, Rex (December 4, 2011) | Part I: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 8, 2011) | Part II: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 12, 2011) | Part III: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 15, 2011) | Part IV: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 19, 2011) | Part V: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 22, 2011) | Part VI: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Pickett, Rex (December 27, 2011) | Part VII: My Life on Spec: The Writing of Sideways (Stage32)

Incidentally, ‘sideways’ is an obscure British slang word for ‘inebriated’ that refers to the staggering motion after one has consumed too many drinks.