Moonlight (2016) Script Review | #6 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Barry Jenkins writes a poetic coming-of-age story told with simplicity yet containing multitudes.

Logline: A young African-American man struggles with his identity and sexuality across the course of his childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Written by: Barry Jenkins

Based on: “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” by Tarell Alvin McCraney

Pages: 98

Scenes: 99

Author Ta-Nehisi Coates summed it up best: “Barry [Jenkins] has this ability to capture black folks in their ordinariness, without making statements or declarations.” Moonlight isn’t an Important story with a capital I; it’s a story that is important because it’s about everyday people, most of whom are broken in their own way. Quiet, powerful, it catches you off-guard like an ocean wave that looks calm but surges in power. It will exhilarate you, amaze you, devastate you.

In a compact 98 pages and across 99 scenes, the Moonlight screenplay is a triptych portrait of a young African-American man struggling with his identity and sexuality at three different stages in his life— as a child, as an adolescent, as a young man. Each Act corresponds to a new stage in his life; in each Act, he’s referred to by a different name. As a 12-year-old boy, he’s referred to as Little in Act 1; as a 16-year-old teenager, he’s referred to as Chiron (his real name); as an adult in his late 20s, he goes by the name of Black. To avoid confusion, when I refer to him by one of the three names, it is connected to the stage in his life that the events are taking place in.

Incidentally, each Act is denoted by a title card that refers to his name, as shown below:

Moonlight is based on an unproduced play by Tarrell Alvin McCraney called ‘In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue,’ drawn from his own life and experiences. When Barry Jenkins adapted it as a screenplay, he remained faithful to its ideas and themes, but moved away from the play’s ‘day in the life’ structure, spreading it across nearly two decades instead with clearly delineated points in time. Another significant change that Jenkins made was to reunite Black and Kevin in the third section of the script, something that didn’t happen in the play.

The pairing of Jenkins with McCraney was a stroke of serendipity. The two had met previously and although Jenkins is straight, he could connect to many elements in the story. Both men grew up in the Miami projects, both had mothers addicted to drugs, and had surrogate father figures. Around the time that the play came to his attention, Jenkins was in a bit of a rut in the movie industry. Although he burst on to the scene with his debut film, Medicine for Melancholy, nobody showed much interest in the projects that Jenkins was pitching— and for eight years, nothing was getting picked up. Luckily, producer Adele Romanski, an old classmate and friend, got in contact with Jenkins. She’d decided to make movies with people she knew and trusted “that could matter to somebody.” After rejecting a bunch of ideas that Jenkins initially pitched— one of which included “a San Francisco police officer scrambling to save the city from an evil genius,” (“like Die Hard on the Bay Bridge”, in Jenkins’s own words)— he suggested McCraney’s play.

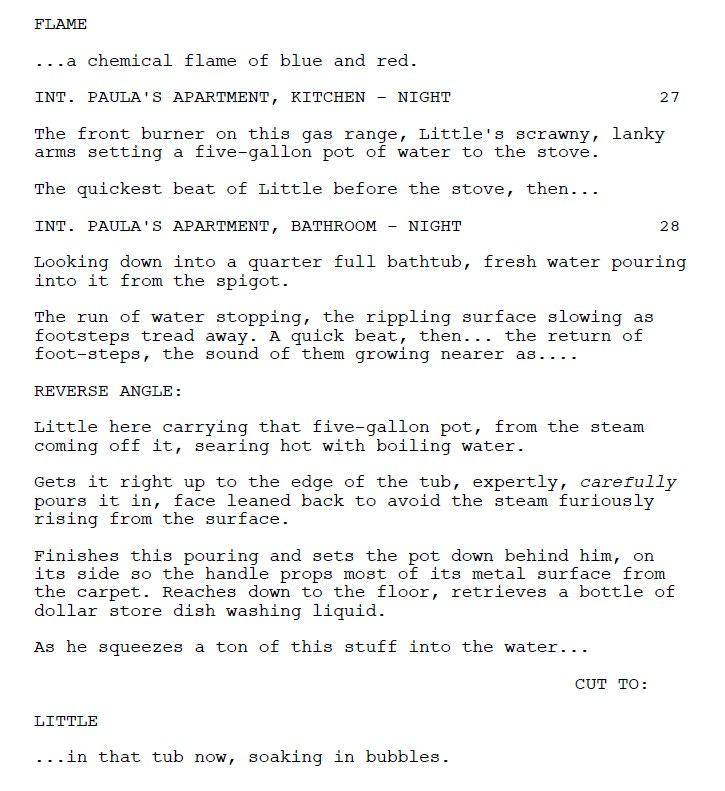

Romanski liked it, too. She sent Jenkins to Brussels for one month (the location was picked on a whim) to work on a draft. Most of the material already existed in the unproduced play’s 45 pages; for Jenkins, it was more about “extending and filling in some of the blanks.” He also brought in some of his own memories— the scene of Little boiling water to soak in the bathtub (Scene 28, page 24) was something that Jenkins used to do. Rather than outlining each beat, he used waypoints as reference to get to where he wanted.

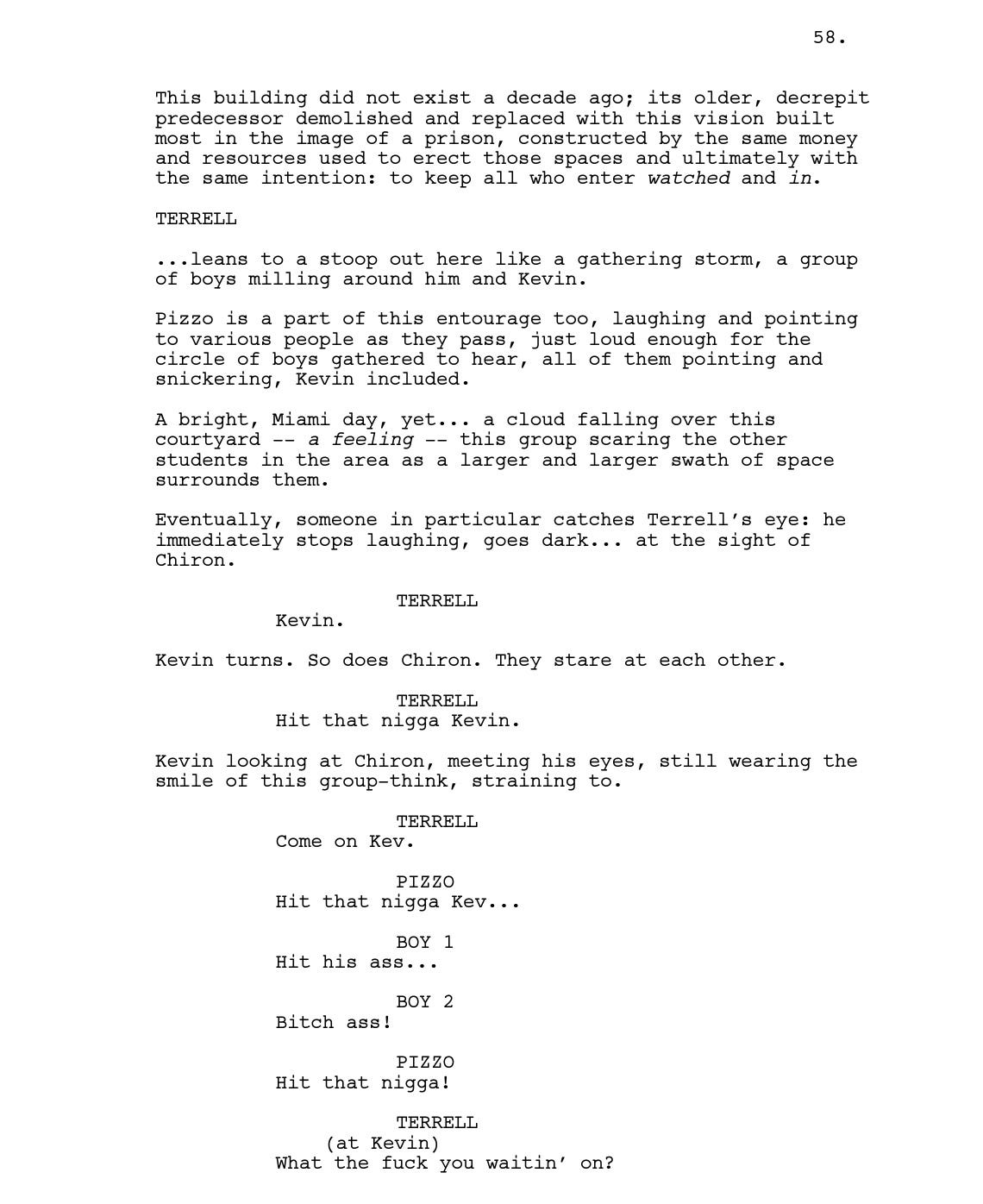

Not having read the play, it’s not easy to distinguish which parts belong to Jenkins or which belong to McCraney, but the overall effect is that the writing is fabulous. From the descriptions, such as describing Chiron’s school architecture resembling that of a prison…

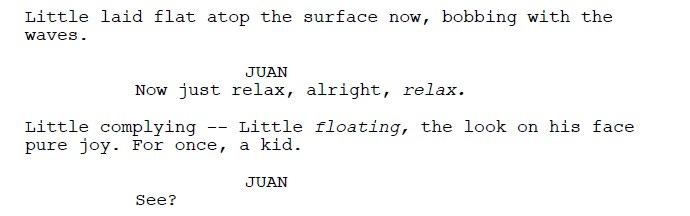

And Little’s joy at learning to swim…

To the way Jenkins captures the voices of the characters with such distinctiveness…

And the way he lands a devastating blow with just a few lines…

And another:

Simply speaks to his prowess as a writer. I also like how he indicates when characters have a new though by breaking the dialogue into separate lines instead of using ‘beat’ or parentheses to break it up, creating a nice flow that makes it easy to read.

Jenkins also introduces characters in ways that immediately tells you all you need to know about a character, without any judgment. For instances, take a look at the opening pages in which Juan is introduced.

Or how Black is introduced to us, where we can more or less gather how his life turned out after he went into the system, without any exposition or even a monologue.

This is made even more explicit when we learn that Kevin also went to prison but instead of going into drugs, he took a job as a fry cook. Even though the hours are long and the pay is low, especially since he has to pay child support, but Kevin considers it honest work. Yet he doesn’t judge his friend for what he does. Every page is filled with a deep sense of empathy, intelligence, and artistic sensibility. The themes of blackness, masculinity, sexuality, and vulnerability are never hammered over the head; they spool out, naturally and unforced, never turning into a lecture, but ever present and visible to see.

Observe, too, the pacing of the script. Some scenes move fast; some slow. None are filler. Each scene is alive. I also like how Jenkins prefaces each Act with sound, as if to signal the shift in time and that we are entering a new stage in the protagonist’s life.

The last scene between Black and Kevin plays out differently in the film versus how it’s scripted, but apart from that, what you read is what you end up seeing; and it is nothing short of stunning.

In many ways, Moonlight would vindicate Jenkins for Hollywood allowing him to toil away without much success for nearly a decade. Not only did he and McCraney win the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay and the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay (weird rules!), it also signaled a shift in tastes with voting bodies as it beat out the heavily-favored La La Land (#92 on the WGA List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century) to win Best Picture1. Although it would be premature to call anything a classic until it’s still being talked about after a decade has passed, I suspect that Moonlight is an exception. It is simply sublime in its greatness.

Notes:

Kohn, Eric (October 19, 2016) | Barry Jenkins’ ‘Moonlight’ Journey: How the Year’s Great Discovery Became an American Cinema Milestone (Indiewire)

Zacharias, Ramona (February 9, 2017) | Barry Jenkins on Moonlight (Creative Screenwriting)

Allen, Dan (October 21, 2016) | Tarell Alvin McCraney: The Man Who Lived 'Moonlight' (NBC News)

Stephenson, Will (October 4, 2016) | Where’s The Next Film, Barry? (The Fader)

Sadly, any story about Moonlight’s triumph at the 89th Academy Awards will mention the unfortunate gaffe when La La Land was mistaken announced as Best Picture before it turned out that Moonlight was the real winner—including this essay.