Midnight in Paris (2011) Script Review | #83 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Woody Allen uses time-travel and 1920s Paris to write a charming screenplay about the power of nostalgia.

Logline: While on a trip to Paris with his fiancée's family, a nostalgic screenwriter finds himself mysteriously going back in time to the 1920s every day at midnight.

Written by: Woody Allen

Pages: 84

Number of scenes: 79

This charming unlikely time travel tale is perhaps the best screenplay that Woody Allen has written in this decade; the Academy Awards definitely thought so, bestowing it the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay at the 84th Academy Awards over other nominees such as Bridesmaids and A Separation (both entries occupy higher places on the WGA’s 101 Greatest Screenplays list). Despite the sci-fi device powering the story, it remains as quirky and funny as you’d expect from a Woody Allen screenplay— it just happens to involve time travel. There’s nothing else quite like it.

Midnight in Paris revolves around a disillusioned young American screenwriter named Gil Pender, who’d rather be a novelist (a stand-in for Allen, perhaps?), would rather live in Paris than move back to the United States, and who thinks he’d be much happier in 20th century Paris specifically than in the present. His fiancée, Inez, encourages his novel writing aspirations as far as a hobby goes instead of telling him to abandon his successful career entirely; her wealthy parents, John and Helen Blair, are flagrantly conservative, terribly tourist, and don’t approve of their daughter’s choice of mate.

One night, Gil takes a late-night stroll, gets lost on a street corner, and at the stroke of midnight, revelers pull up in a car and invite the bemused American to join them. The car is the vehicle that allows Gil to travel back in time, where he suddenly finds himself at a party serenaded by Cole Porter and hanging out with Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and later, Gil’s literary idol, Ernest Hemingway.

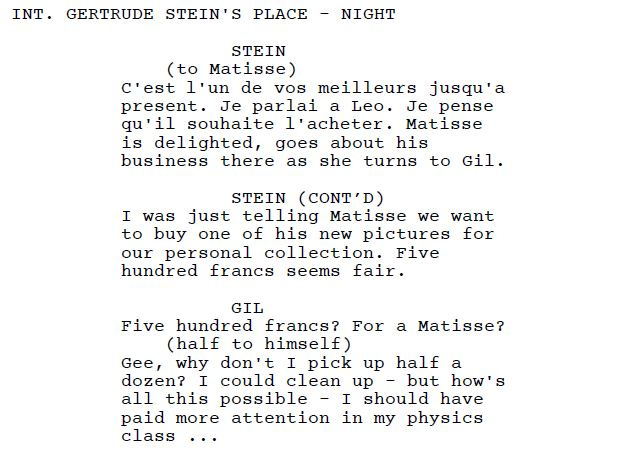

In most screenplays, pages would be devoted to the mechanics of the time travel. How does it work? Allen doesn’t say, although he jokingly refers to this on page 68 when Gil laments at not paying better attention in his physics class.

Allen had his reasons for not getting into the weeds of the mechanics: He wanted to create a world with a fairy tale aspect, in which logic does not make sense, but we accept the confusion as the price for so attractive a story. It’s what you might call ‘lo-fi sci-fi,’ one in which expensive effects aren’t required to tell a time travel story, instead focusing on the more interesting aspects. As Hemingway puts it himself at one point: “No subject is terrible if the story is true.”

However, if the story had consisted entirely in diving back into 20th century France to parade the literary icons and famous names living in Paris during that time— there’s Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Matisse, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, Luis Buñuel, Djunu Barnes, T.S. Eliot, and a non-speaking appearance by Ezra Pound! — Midnight in Paris would get repetitive and tired quickly. Enter Adriana, Picasso’s fictitious mistress. Gil is drawn to her; Adriana in turn is drawn to Gil. Suddenly, Gil’s trips to the past take on a new urgency greater than simply hanging out with his idols, or having Stein look over his manuscript, or simply living in the past—literally! In Adriana, he finds a connection that he doesn’t have with Inez (who, in turn, is having a fling with the pedantic scholar, Paul); now, there is dramatic conflict and a central question: Will Gil cheat on Inez? Will he remain in the past and not return to the 21st century? (Okay, that’s two questions.)

The Midnight in Paris screenplay is dominated by large tracts of dialogue and has little action lines. Part of this is due a formatting issue where the action lines have gotten accidentally included with the dialogue; but even then, they would still be quite brief. As for description, Allen doesn’t seem to believe in it. He indicates the location in the slug line, mentions the action if there’s any, and then dives into the dialogue. Considering that Allen has an ear for writing naturalistic and funny dialogue that simultaneously fleshes out the themes and conflict without feeling forced, it makes sense to write this way.

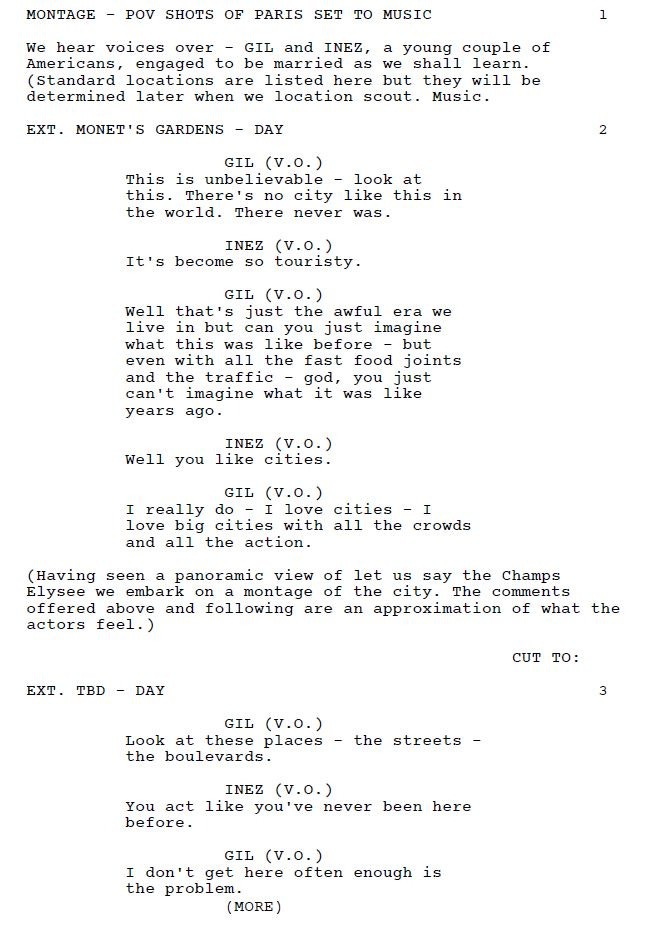

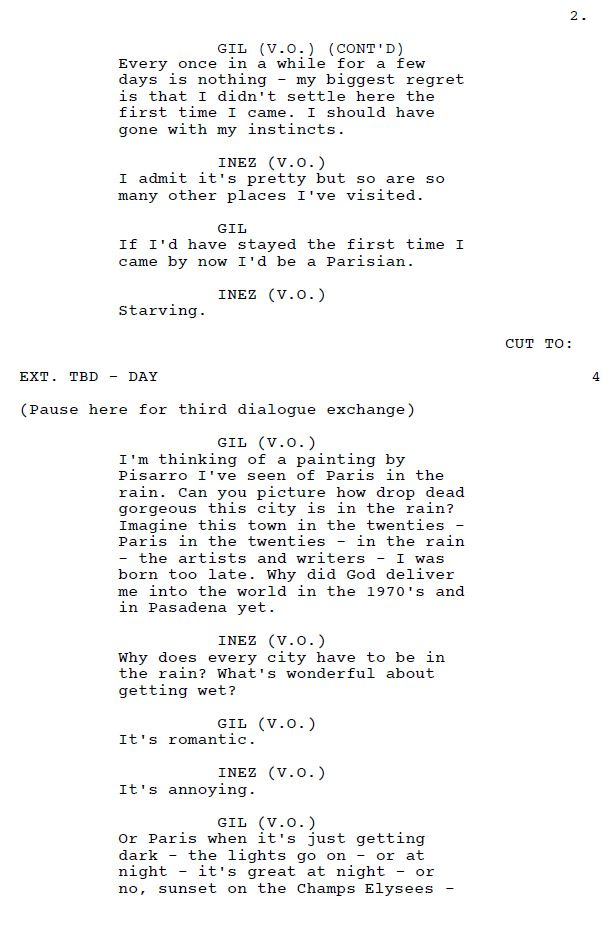

For instance, take a look at the opening scene.

It consists mostly of a verbal exchange between Gil and Inez, told over a montage of Parisian scenery that adds up to four pages, before we catch a glimpse of the couple. But in those four pages, Allen outlines their different personalities, establishes the theme, and plants the seeds for the ensuing conflict:

Gil Pender:

Screenwriter but wishes he was a novelist;

Likes Paris but wishes he’d been born in a different time;

A romantic;

Engaged to Inez.

Inez Blair:

Likes Paris but only in the touristic sense;

Cannot envision living outside the United States;

A pragmatist (and more materialistic);

Engaged to Gil.

The common advice in screenwriting is to ‘Show, don’t tell,’ advice that Allen subverts by showing through telling! He gets away with it by simply adding conflict into all his scenes— the mere presence of clash generates some form of drama. Here, it comes in the form of politically opposed views between Gil and John…

… or Gil one-upping Paul at a gallery to correct the pedant’s analysis of a Picasso painting by using Gertrude Stein’s criticism.

Above all, there is a character journey which provides the spine of the screenplay. Gil goes from yearning to live in the past to accepting the present with all its foibles when, in 20th century Paris, he and Adriana travel back further to the past; where the 1920s of Paris were the Golden Age for Gil, the 1800s are for Adriana, and for Adriana’s idols, the Golden Age was the Renaissance. Nostalgia is a trap, Allen seems to be saying. Just as living in a different country is not the same as visiting it, Allen suggests that should Gil and Adriana live in their idealistic past, it’ll become their present and the discontent will start all over. Finding confidence in his manuscript, Gil breaks off his upcoming nuptials with Inez and opts to stay in Paris.

The script contains instances of French dialogue; at one point, there is Spanish. In both cases, they aren’t provided an English translation. Compare that to The Farewell (#91 on the WGA’s List of Greatest Screenplays), which was predominantly in Mandarin— in that script, everything was written in English with Mandarin dialogue shown in square brackets. Allen, probably being a Francophile, could get away with writing French (not to mention that France was providing the financial backing). But as an aspiring screenwriter, if you have to include non-English dialogue yet you don’t speak the language, simply write it out in English and indicate in parenthesis that it’s in a non-English language.

Writers often get asked from where they get their ideas. For this script, Allen started with the title (and it is a catchy title)— and then spent the next six weeks trying to figure out what happened in Paris at midnight. The image of Gil walking down the street and a car pulling up to invite him on an adventure helped guide Allen through the writing process. The other idea was to make it a romance because Paris in movies had always been portrayed as a city of romance.

Who is Woody Allen?

Woody Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg on November 30, 1935) is an American filmmaker, actor, and comedian with a career spanning over six decades. He began his career as a television writer in the 1950s alongside other luminaries such as Neil Simon, Mel Brooks, and Carl Reiner, while publishing short stories and humor pieces for The New Yorker. A foray into stand-up comedy led to three comedy albums (earning a Grammy Award nomination in 1964), and around the same time, he moved into filmmaking starting with his first feature film, What's Up, Tiger Lily? in 1966. This eventually led to a long-running partnership with United Artists, including Bananas (1971) and Sleepers (1973) but it was Annie Hall (1977) that firmly established himself as a unique comedic voice (beating out Star Wars at the Academy Awards that same year in the Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay categories). Over the years, he’d explore a wide range of genres from romantic comedies like Manhattan (1979) to more dramatic works like Crimes and Misdemeanours (1989) and Blue Jasmine (2013). Allen has received several accolades, and holds the record for the most Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay (16 nominations and 3 wins).

Now comes the question: Given Allen’s controversial history, should you read Midnight in Paris? I’ll admit, the spell of the script kept breaking whenever Allen’s personal life popped into mind, or when it’s implied that the older Gil might enter a relationship with a much younger Parisian woman named Gabrielle at the end of the screenplay (it felt a bit ick). But on its own merits, Midnight in Paris is among Allen’s, if not best, then most charming work. Despite everything, the man absolutely has a knack for comedy. Midnight in Paris is a wonderful example of how to incorporate science fiction concepts and devices like time travel without needing to spend time on getting technical. It offers an alternative approach while mixing up genres, so long as it has the usual elements of drama and conflict. I guess: hate the scriptwriter, and not the script?

Notes:

Itier, Emmanuel (May 24, 2011) FILM INTERVIEW: WOODY ALLEN The Beloved Director Spends 'Midnight in Paris' with Stars Owen Wilson & Rachel McAdams | Buzzine