Michael Clayton (2007) Script Review | #20 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A gripping legal drama for adults, Tony Gilroy grapples with corruption, morality, and corporate rot that feels even more despairing today.

Logline: A law firm brings in its ‘fixer’ to remedy a situation after a lawyer has a breakdown while representing a chemical company that he knows is guilty in a multi-billion-dollar lawsuit.

Written by: Tony Gilroy

Pages: 126

Tony Gilroy likes to write realistic adult dramas, often about broken people or corrupt systems. In Michael Clayton, he has both. It’s a legal thriller, but one that never ventures inside a court; it draws from the tradition of films made in the 1970s, such as The Conversation and All the President’s Men—big, yet intelligent. The result is a script that grips from start to finish.

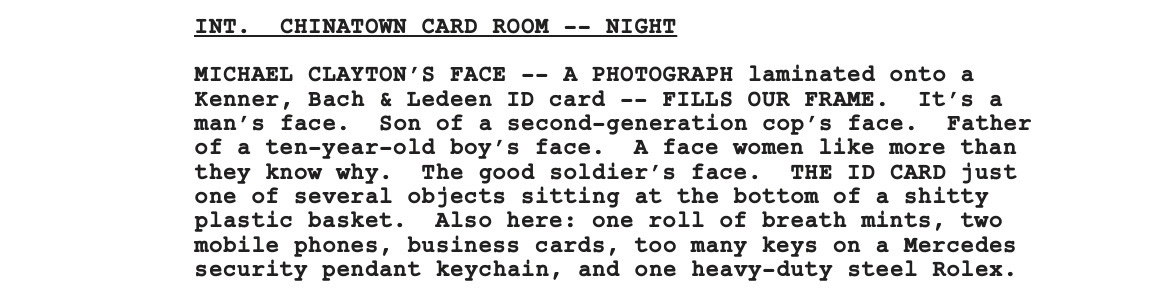

The story is told in media res. It begins near the end, as Michael Clayton is called in to fix a hit-and-run problem, before narrowly escaping death when his car blows up. The script then flashes back to four days earlier. Arthur Edens, the star attorney at Kenner, Bach & Ledeen, has suffered a breakdown that could cost the law firm losing the account of chemical company U/North. Michael, who is friends with Arthur, is sent to do what he does best. He’s a fixer. He cleans up messes. When you got problems, Michael Clayton is your man.

Here’s the problem: Arthur has had a moment of clarity. He doesn’t want to keep defending a client in a three-billion-dollar class action lawsuit when he knows they are guilty. U/North is panicked because Arthur has in his possession a memo that proves the company knowingly caused harm. They want the memo back, especially Karen Crowder, the general counsel for U/North. Her desperation to suppress the memo leads her to hiring two hitmen to silence Arthur. Michael, on the other hand, just wants to make sure Arthur is okay. It’s not just business; he considers Arthur a friend.

Michael has his own troubles. He’s never advanced far in his career, and talks of a merger makes his position precarious. He’s also divorced, and doesn’t always seem to be around for his son, Henry. More pressingly, he’s got money troubles: a restaurant he opened went belly-up because the business partner, Timmy, screwed up; now he has to pay off a loan shark fast. Gilroy really likes to load his protagonist with problems!

Since this screenplay is about a character, it takes the time to show him from different angles. We see how he is at work, and how he is with his son. The script dwells significantly on his personal life, which includes Gabe, his cop brother; Timmy, incidentally, turns out to be his brother, which is why Michael was reluctant to disclose his whereabouts. These relationships are the crux to understanding Michael.

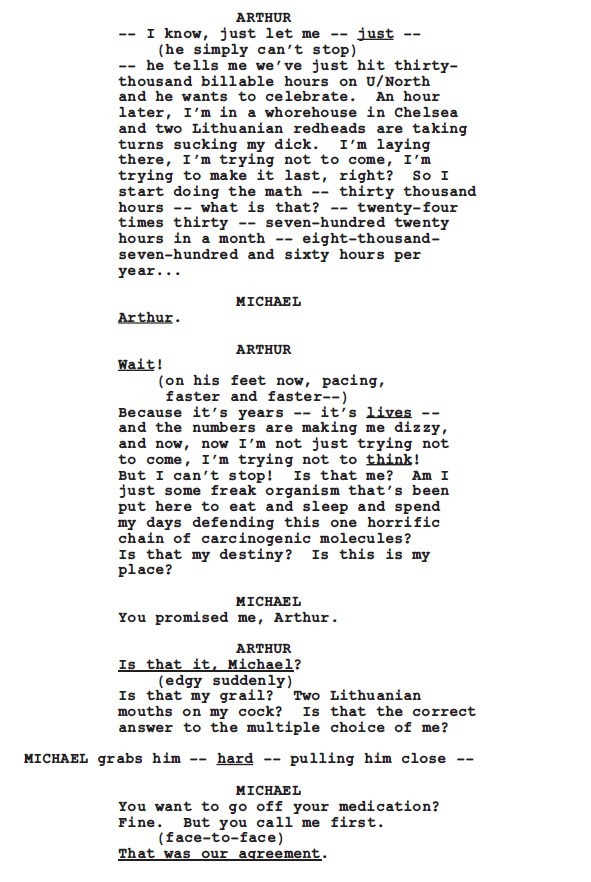

But perhaps the most important one is his relationship with Arthur. Although Arthur is a manic depressive who stopped making his medication, his lucidity forces Michael to question his life and the choices he made. It happens twice, first on page 46, when Arthur catches Michael off-guard with a direct question…

… and during a face-off with Arthur when the latter calls him out.

This doesn’t exactly help Michael, though it makes for undeniably great drama. It’s not enough that Karen calling in two hitmen will endanger Michael’s life, too; it’s that there is a creeping dread that Michael’s life isn’t a good one. Gilroy avoids turning Michael into a saint by the end; such a 180-degree-turn would be unrealistic. But his desire to avenge Arthur’s death forces Michael to reckon with his choices and decisions. He takes a bold step in incriminating Karen and sticking it to U/North; when he gets into the cab and leaves in the end, he’s still the same guy, but he’s taken a step in doing something good, just as Arthur was trying to do.

This script is packed with dialogue. Entire pages of it, sometimes. But thanks to balancing conflict and tension, the lines read like poetry, especially the scenes with Arthur Edens.

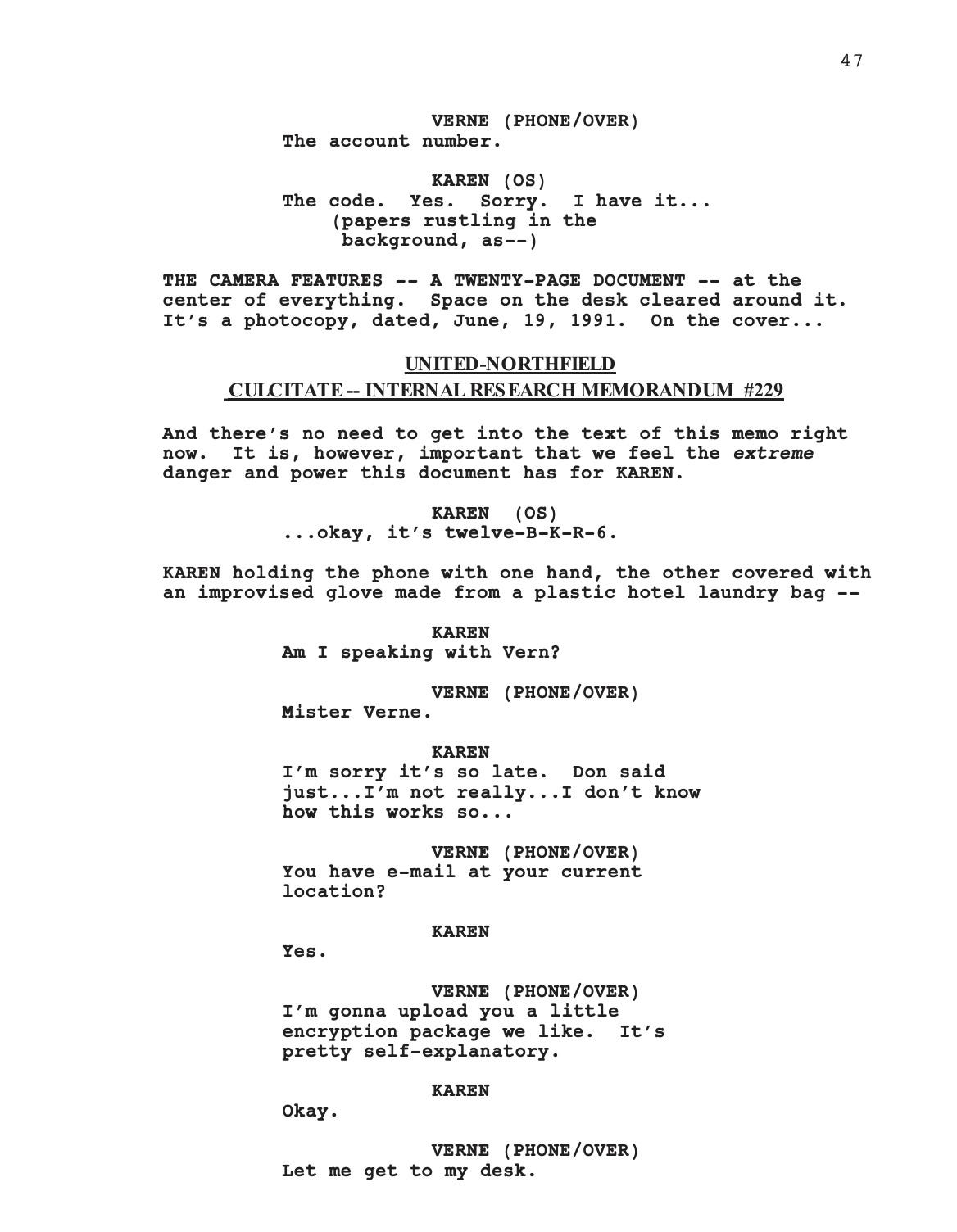

Moreover, Gilroy knows how to effectively build dread and tension into the story, even in something as innocuous as a memo.

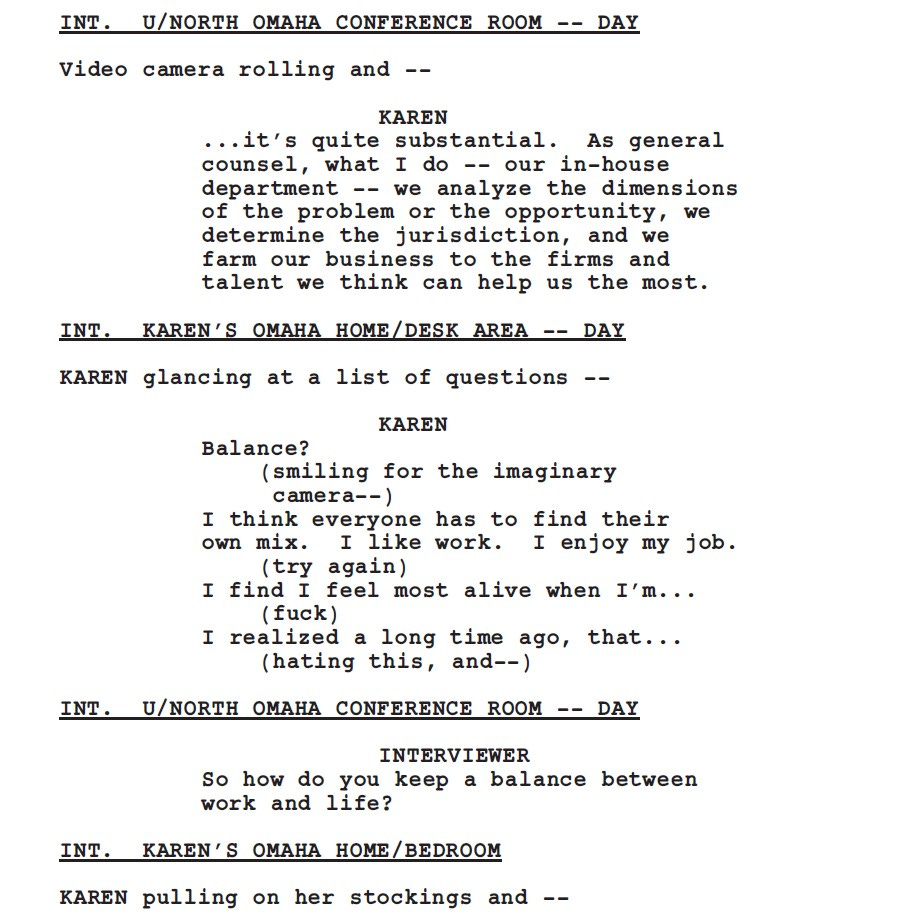

The other character who shines is Karen Crowder. She’s not evil so much as she is pushed to doing bad things in an act of self-preservation. Gilroy opted to do something that is rarely, if ever, done today. He wanted to write the moments in a villain’s story that gets left out of films: the moment when they cross the line into villainy, and become the villain.

Karen, it should be noted, is not a monologuing villain who loves to gloat. She’s simply doing what she thinks is best for U/North. In many ways, that makes her scarier because how many Karen Crowders might be walking around us? People who justify horrible actions in the name of their job?

Gilroy’s writing is fascinating. Look at how he describes Michael…

… and then cleverly smuggles in exposition about Karen through her rehearsing for an interview.

The same applies for writing phone conversations, which hard to visualize cinematically. What he does is simply use “PHONE/OVER” without mentioning to cut back and forth between scenes and take up space.

Gilroy is not a writer you’d immediately think of as ‘talky’ but his ability to write reams of dialogue in a thriller is remarkable. In addition, in the first four pages, he sets the world, tone, theme, premise, and introduces the main character with resounding swiftness. The theme, incidentally, is that law firms protect powerful entities who knowingly approved a product they knew could kill people, and chose to fall in line rather than stand up to them, as Arthur did.

Michael Clayton was inspired by the real-life corporate malfeasance of the defective Ford Pinto, when an internal document came to light that Ford opted not to recall the problematic vehicles because it would be cheaper to let people die and sue them. Another source of inspiration happened early when researching for The Devil’s Advocate; Gilroy realized that law firms in movies look nothing like those in reality. A third stroke of fortune was the idea of following a man whose failures and disreputable line of work made him too self-aware. Accordingly, Michael is past redemption, has squandered opportunity, and perhaps even in life; his actions in exposing Karen is a small note of salvation. When writing, Gilroy recommends starting with a small idea, and then building it up. Here, he started with ‘fixer’ and ‘law firm’; after that, he created the logline, all this before he started writing.

Tony Gilroy comes from a family of writers and filmmakers. His father, Frank D. Gilroy, was a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and filmmaker; his brother, John Gilroy, is an editor; and his brother, Dan Gilroy, is also a filmmaker (his script, Nightcrawler, is #53 on this list). His flair for arresting prose, gripping tension, and powerful dialogue makes him a formidable force. He is that rare screenwriter: someone capable of blending adult themes, moral complexities, and entertainment all together.

Notes:

Parker, Dylan (December 23, 2020) | The Surprising Real Story That Inspired 'Michael Clayton', According To George Clooney (The Things)

Dawson, Nick (October 5, 2007) | Michael Clayton Director Tony Gilroy (Filmmaker Magazine)

Keogh, Tom (October 7, 2007) | Director interview | Tony Gilroy, “Michael Clayton” (The Seattle Times)

Miyamoto, Ken (March 16, 2016) | Oscar-Nominated Tony Gilroy's 7 Guidelines to Writing an Original Screenplay (Screencraft)