Nightcrawler (2014) Script Review | #53 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A deliciously unsettling and taut thriller with a suitably unsettling yet compelling antihero to grace the screen.

Logline: Desperate for work, the unemployed Lou Bloom muscles his way into the world of L.A. crime journalism. Aided in his effort by a TV-news veteran, Lou begins to blur the line between observer and participant, doing whatever it takes to rise to the top.

Written by: Dan Gilroy

Pages: 99

At a clipped 99 pages, Nightcrawler simmers with the same ferocious intensity of its antihero. Lean, menacing, and hypnotic, it is impossible to tear your eyes away from this perverted rags-to-riches story about Lou Bloom, a hustler who fights his way to the top and wins— by any means necessary. It’s a dramatic thriller that has plenty on its mind about capitalism and unemployment in America. It feels like the true face of the American Dream, and it is the face of a sociopath.

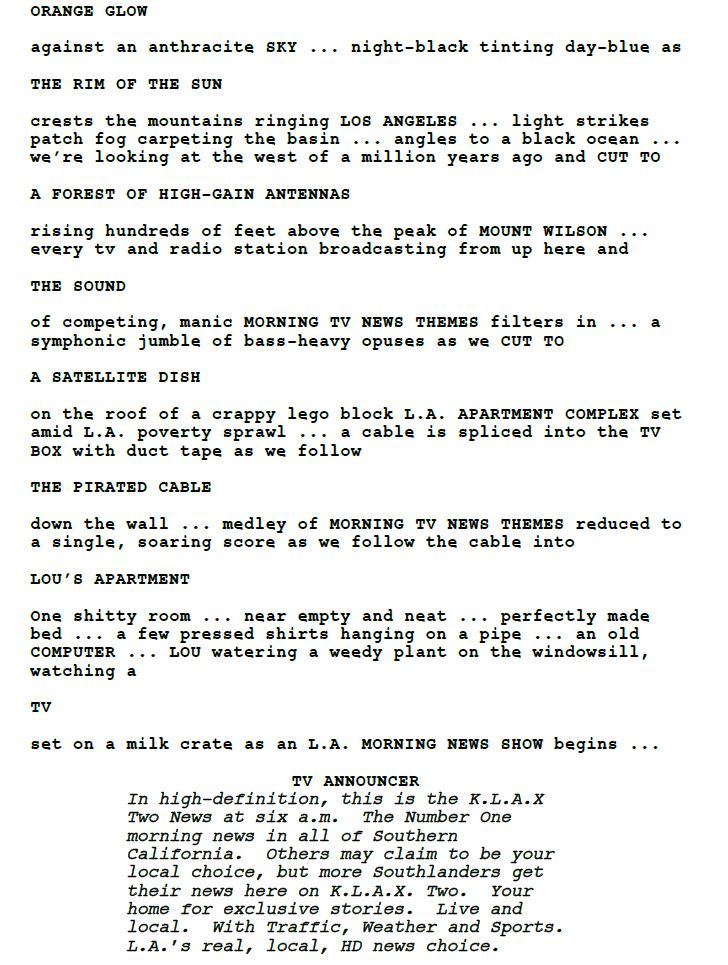

Lou Bloom, unemployed, needs money. He lives in Los Angeles— not the glamorous section we usually see, but in the most industrialized part of town. When the script begins, Lou is cutting chain-link fence to sell for scrap value. He gets caught by a security guard, and attacks him to get away. Lou tries to get a job from the scrapyard owner but is flatly rejected: he doesn’t want to hire a thief.

On the drive home, Lou spots Joe Loder, a veteran ‘nightcrawler,’ filming the site of a car crash. He finds out that news channels pay money for this kind of footage. Intrigued, Lou buys a cheap camera and police scanner (stealing a bike to fund them), and captures his first footage of a shooting victim. He takes it to KWLA, a channel that thrives on this kind of material, and encounters TV-news producer Nina. Lou makes the sale. He sees the potential to make more. He hires an assistant, Rick— taking advantage of his unemployed desperation— and slowly builds a business. By the end, Lou has grown his little venture into two news vans and is aided by three interns. For all intents and purposes, this is a happy ending.

So why are we left feeling uneasy by the last page? I venture the possibility that it’s because we know Lou did unethical things to achieve his success. He takes out the competition, in the form of Joe Loder, by cutting his rival’s brake lines and sending him into an accident. He begins to insert himself into the stories he captures, even staging the scenes for more dramatic effect. Poor Rick gets killed because he tried to pull one over Lou. For Lou, getting the footage is everything. The ends justify the means.

You can’t help feeling sorry for Lou because he’s only trying to survive. You also can’t look away as you realize he is a tumor born of a capitalist system. Lou is an entrepreneur, and America loves entrepreneurs! He identifies a market, finds a demand, and provides the supply. The system rewards those who can clearly identify a gap in the market. Lou’s amorality also allows him to exploit this to the hilt. He is a hustler— every other word that comes out of his mouth sounds like he’s been fed solely on a diet of self-help books. You get the impression he believes in the message but when it comes out of Lou Bloom’s mouth, it reeks. See for yourself:

Rick, then, serves as the audience surrogate. He is the voice of reason, and refuses to worship at the altar of capitalism. He balks at crossing lines for profit. In the end, Rick dies because he has some ethics while lacking Lou’s hustle ethic. It’s a dog-eat-dog world, and the Ricks of the world simply don’t make the cut. And that’s why he’s unsuccessful. In such a story, it’s important to have a Rick character— an avatar who questions the antihero’s methods, and is impacted by such methods.

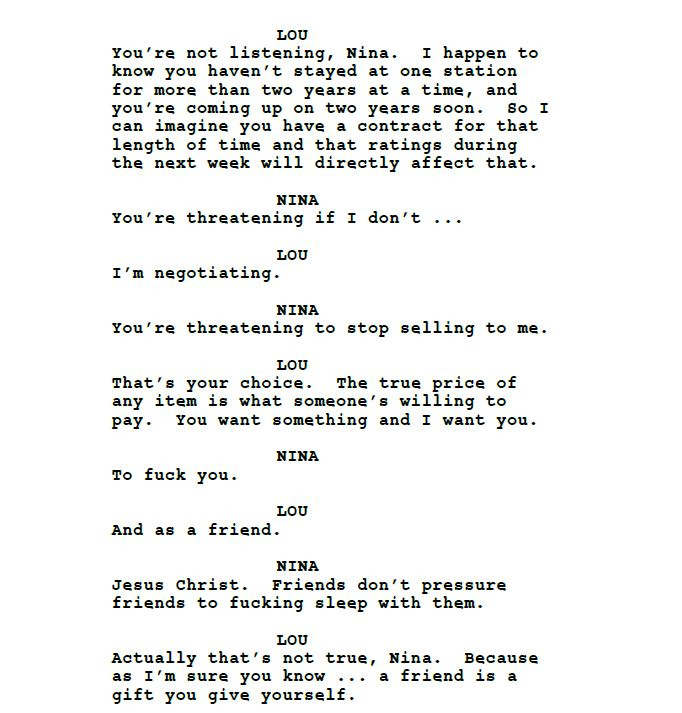

Given its remarkably short length (the average script is about 120 pages), each Act in Nightcrawler amounts to roughly 30 pages each. Act 1 concludes on page 32, by which time Nina, Rick, and Joe have been introduced in the script. Act 2 runs from page 33 and ends at around page 62— during which Lou slowly consolidates his bargaining position; and Act 3 lasts 36 pages, which mainly involves Lou leveraging a hot story from Act 2 to ‘stage’ the capture of some wanted criminals in a highly publicized home invasion (that Lou also happened to record before the police even arrived). In doing so, Lou boosts his profile, the ratings at KWLA, and helps consolidate Nina’s producer power. Even when detectives try to pin Lou for withholding evidence, Lou slips out from their snares. He wins it all: money, status, prestige, and even gets the girl. But the way he does it is less than ideal— observe, for instance, how he gets the girl:

The origins of Nightcrawler are its own tale. Writer Dan Gilroy (sibling to Tony Gilroy and John Gilroy) initially wanted to make a picture about American photographer, Weeger, back in the late ’80s. But upon discovering the stringer profession, Gilroy switched gears… only to run into several problems, the worst being that he couldn’t find a plot that was satisfying. He experimented with murder mysteries and conspiracies, but it amounted to nothing. After that, Gilroy changed his approach and started with the character (always advisable!), only to encounter a bigger problem: He couldn’t make his lead character interesting! Nothing worked until he finally decided to turn Lou Bloom into an anti-hero, drawing inspiration from The King of Comedy, To Die For, and The Talented Mr Ripley. At once, the story began to take form.

Like the story, the writing is lean and clean. It has brevity, and is very visual in the way it is written. Gilroy accomplishes this by using sluglines to emphasize particular shots, allowing us to see the image more clearly in our heads as he envisioned it.

Lou Bloom is one of the most fascinating antiheroes to hit the big screen. Antiheroes were popular on television in the 21st century— Walter White, Tony Soprano, and Don Draper, for instance— but antiheroes in cinema were comparatively less. But what makes Lou— and the aforementioned television antiheroes— compelling is that they all have human problems that the audience can relate to. As I mentioned, Lou has money troubles and is desperate. We can empathize with his dilemma. Walter White wants to leave his family financially secure when he dies, and also find something that gives his life meaning. We can empathize. We empathize even as their behavior in the pursuit of their goals grows increasingly unethical. If not financial troubles, maybe antiheroes are looking for love, or shelter. Maybe they are just trying not to starve. To write a three-dimensional antihero, you need to make sure that their need is easily understood, so that when your antihero starts behaving disturbingly, the audience is willing to make excuses and justify their actions.

What’s notable, however, is that unlike the other famous antiheroes, Lou Bloom has no back story. We don’t learn anything about his background or his life. Gilroy purposefully left Lou’s history a mystery. In an interview, Gilroy stated that the opening of Nightcrawler, in which Lou cuts chain-link fence, implies that Lou is a criminal who has lost his morality as a result of the job. It is, in fact, Lou’s lack of morality that allows him to gain from the system because he knows the system will reward his behavior. Omitting reasons for why a character behaves in a particular way is a method to create intrigue.

Although it would take Gilroy two decades to make a movie from his script—which also became his directorial debut— the patience paid off. He won numerous awards and nominations for Nightcrawler, including an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay (and losing out to Birdman: Or the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance). It is a first-rate 21st century thriller, a twisted cautionary tale about capitalism in all its carcinogenic glory. Lou Bloom started from the bottom and rose to the top, and so can you. The question is, how far are you willing to go to get what you want?