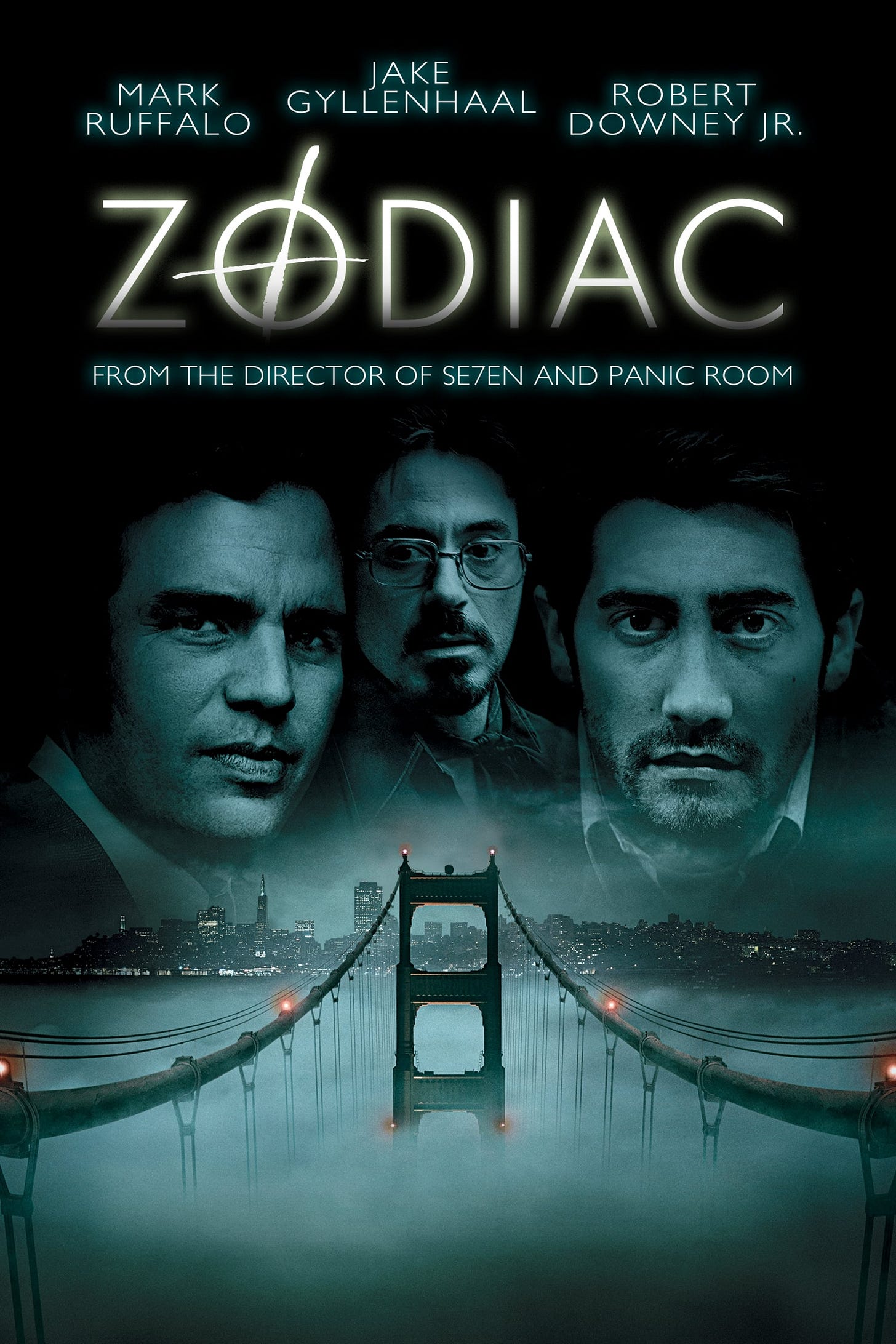

Zodiac (2007) Script Review | #46 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A foreboding thriller about unmasking the Zodiac Killer and the obsession with the case that forever consumed the lives of three different individuals.

Logline: In the late 1960s and 1970s, a serial killer called Zodiac strikes terror in the San Francisco Bay Area, taunting the authorities with his ciphers and letters. As the body count and clues climb, the case becomes an obsession for four men as their lives and careers are built and destroyed in the hunt to bring Zodiac to justice.

Written by: James Vanderbilt

Based on: Zodiac and Zodiac Unmasked by Robert Graysmith

Pages: 194

Scenes: 242

Who was the Zodiac Killer, and did a cartoonist really come the closest to catching him? Nobody knows, and even James Vanderbilt avoids committing to an answer. Instead, his screenplay chooses to move in the same waters of ambiguity and uncertainty when a serial killer struck terror during the late 1960s and early 1970s in San Francisco. It is an intelligent script, a whopping 194 pages long, and it thrums with suspense and intrigue, evoking classics such as Chinatown and All The President’s Men. No, from Vanderbilt’s point of view, the identity of the Zodiac Killer is less interesting than the ways in which the investigation consumed, made, and destroyed the lives and careers of four different men.

The four men are unlikely bedfellows. There’s Robert Graysmith, a shy cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle; there’s Paul Avery, the paper’s perpetually drinking crime writer; and there’s Inspectors Dave Toschi and Bill Armstrong, the lead detectives. The first half of the screenplay focuses on Toschi, Avery, and Armstrong, while Graysmith lingers on the sidelines until he takes over the story around page 131. Most writers and screenwriting gurus would tell you that it would be suicide to:

a) keep your main character passive;

b) avoid your main character being the focus until the last 60 pages.

Perhaps not suicide, but it is unusual. But it works because Vanderbilt remains faithful to the real-life events. That Graysmith only became truly obsessed with the case a decade after everyone else moved on, as what happens here, reflects the way in which it really happened.

Zodiac turns procedural investigation into an exercise in tension. The screenplay is based on two Graysmith books, Zodiac and Zodiac Unmasked. The plot unfolds over 20 years; page 1 to 131 covers the years roughly between 1969-1972 or 1973, and page 132 to 189 condenses the next several years until 1989, before wrapping up with a brief epilogue set in 1991. All of this begs the question: how do you turn a procedural investigation of this kind into a riveting screenplay?

Answer: By largely adhering to the usual conventions of cinema, but at a trickier level.

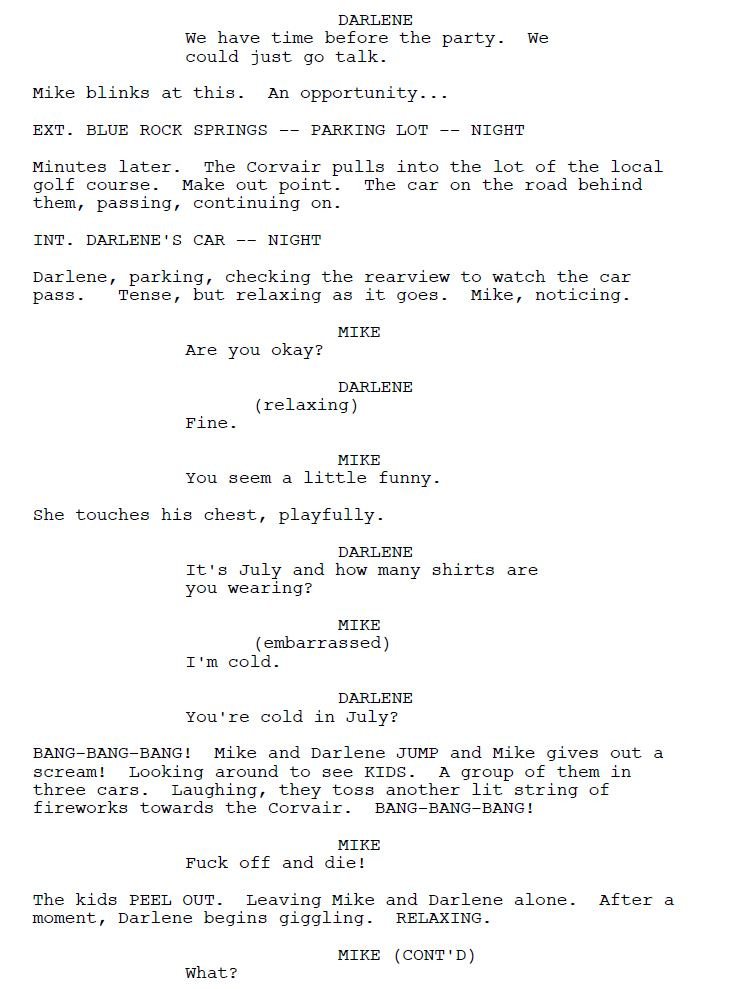

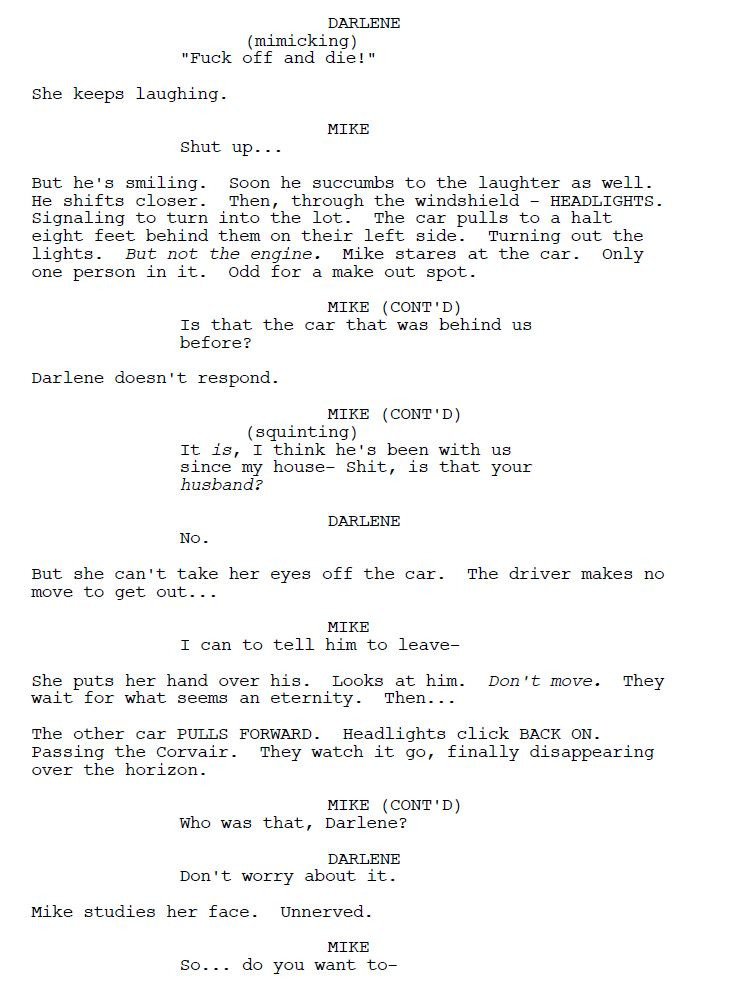

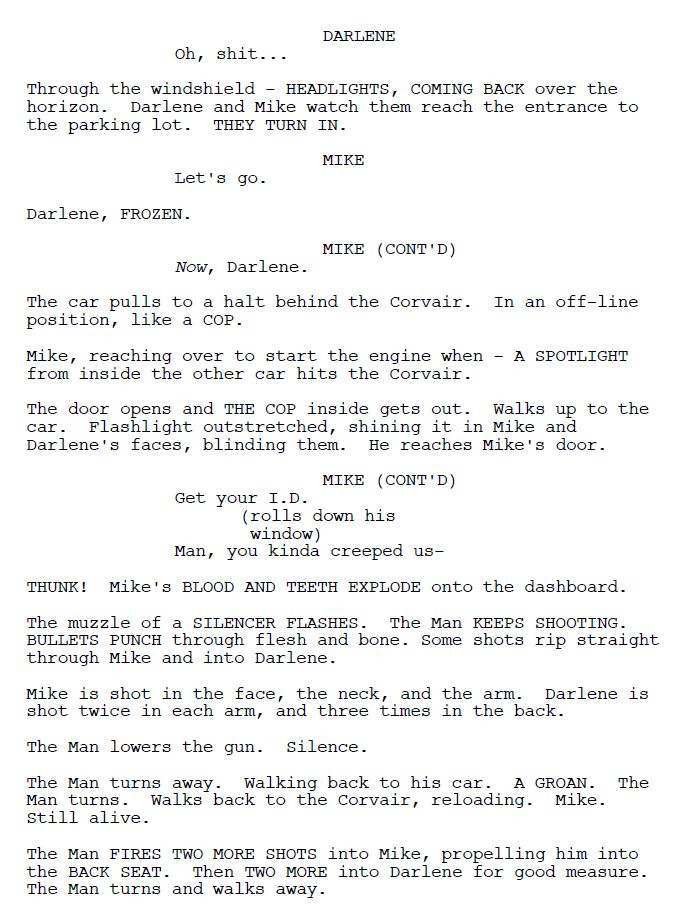

For one, you begin with the shooting that killed Darlene Farleigh and destroyed the life of Mike Mageau on July 4th 1969. You use this scene to build tension and set the tone, but also to bring back full circle when an older Mageau identifies from a list of suspects the man he saw that night. Vanderbilt structures the scene like a horror film. Two teenagers end up somewhere secluded, there’s a jumpscare (fireworks lit by teenagers); the unease builds when a car comes up, lingers, then drives away; until the tension literally erupts in a burst of gunfire.

For another, you have memorable characters. With a few lines of dialogue and description, Vanderbilt introduces Graysmith as a divorced dad, a nerd, and a cartoonist.

Vanderbilt introduces Avery with the man cracking a joke, immediately making it clear that he’s the popular kid who holds forth in court.

Toschi and Armstrong, who enter the story around the beginning of Act 2 on page 38, have strong personalities. Toschi is smart, and stylish; he served as the inspiration for Steve McQueen in Bullitt. Armstrong is effective and considerate. Their partnership and history is conveyed at once in a simple gesture, when Armstrong knowingly offers a box of animal crackers to Toschi on the way to a crime scene.

A good lesson for aspiring writers: If you want to sum up a strong friendship or partnership in a few actions, have one character give the other some food or drink that they like. It has the same effect as in real life; it shows they know each other very well.

Soon, these personalities will mix and clash. An unlikely friendship grows between the older Avery and the awkward Graysmith; later, Graysmith will build a collegial if occasionally tense rapport with Toschi after Armstrong decides to transfer departments and leave Zodiac in the rear-view mirror.

There’s also the mood. A constant dread permeates the script, especially as leads turn to dead-ends, clues amount to red herrings, and the Zodiac Killer continues to taunt the police and city. There are three scenes in which the Zodiac Killer appears, but his face is never shown. But the most memorable moment in the entire script occurs in Scenes 219-221, when Graysmith visits a man who may hold the clue to the identity of the Zodiac Killer… only to be struck with the possibility that the man may actually be the killer! Although no violence occurs, the part when Graysmith walks down into the basement and possibly his doom, is a masterclass in building suspense. It requires planting several clues such as the Zodiac Killer having a basement in California, not many houses in California having a basement, and that the man, Vaughn, has a house in California with a basement!

And then there are the ways in which we see the main characters affected by Zodiac. Avery received a direct threat on his life after making fun of the killer in the papers; it’s implied that it drove him to suffering from health issues. Toschi’s career never progressed beyond Inspector the longer the killer eluded the police, especially after a charge was brought against him for forging a letter to revive interest in the Zodiac case to boost his profile. And Graysmith? Despite becoming a prominent expert in the Zodiac case due to his obsession, it cost him his second marriage with Melanie.

Vanderbilt spent a year writing Zodiac on spec in exchange for more creative control. He was drawn to two aspects of the story. One was the ‘fish-out-of-water’ angle in which a cartoonist got sucked into the case. The second was the uncomfortable ambiguity that there is no definite answer to the Zodiac Killer’s identity, because he was never caught. The given ending shows the people, especially Graysmith, finally being able to move on with their lives.

When David Fincher signed up as director, Vanderbilt found a supportive collaborator. Fincher always had a reputation for meticulousness and here, he honed in on the accuracy of the facts. He asked Vanderbilt to rewrite the script to include the police reports that brought in the sides and evidence of the police to back up the accuracy. They also conducted their own interviews and documentation. A laborious process, it required director and screenwriter to sift through mountains of information and decide what to keep and what to leave out. One thing that they did was to include Graysmith as a character and have the story unfold from his perspective; the books, in comparison, merely recount the case.

A note where tackling dark subject matter is concerned. Just because its grim doesn’t mean the script has to be 100% serious. A little humor goes a long way. Police officers deploy gallows humor to cope with the grim things they encounter on a daily basis. Zodiac has a healthy dose of levity, particularly courtesy of Avery as well as Graysmith’s social awkwardness.

The lesson being: If you are writing a serious story, insert a few jokes here and there.

It’s worth paying attention to some of the techniques Vanderbilt uses to make his writing stand out. He doesn’t hesitate to use camera directions, but uses it only rarely.

He uses onomatopoeia to bring sound to life, such as “CLICK”…

… or “DING!” …

And his prose is spare unless required. I mean, just look at the way he writes the scene where Graysmith meets the likeliest candidate for the Zodiac Killer towards the end, a man named Arthur Leigh Allen.

Zodiac is brave in its refusal to sensationalize a true crime story. Instead, it is a story about how the shadow of evil marked the lives of several people. The mere fact that it cannot offer a definite identity to the killer only makes it more compelling and scarier. It’s a long read but when you reach the last page, it will leave you shaken.

Notes:

Faye, Denis (2007) | The Messiness of Life and Death (Writers Guild of America)