Whiplash (2014) Script Review | #32 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Taut, tense, and riveting, Damien Chazelle brings out the darkness in this drama by approaching it as a thriller, to wildly successful effect.

Logline: Under the direction of a ruthless instructor, a talented young drummer begins to pursue perfection at any cost, including his relationships and his humanity.

Written by: Damien Chazelle

Based on: Whiplash (short film) by Damien Chazelle

Pages: 105

Scenes: 108

In some ways, it’s almost a kinda fucked up love story. A razor-sharp, high-wire act; a cautionary tale about an aspiring drummer and his abusive instructor; and the perils of chasing greatness, written in the vein of a psychological thriller. Though ostensibly a drama, every page evokes the uneasy vibe of Rosemary’s Baby or an Alfred Hitchcock picture.

Andrew Nieman, a first-year student at Shaffer Conservatory, wants to be the best drummer of his time. An opportunity to be in the band of the school’s most prestigious instructor, Terence Fletcher, might help him get there. From timid and even unsure of himself, Andrew grows confident, even summoning the courage to ask out a girl on a date. But Fletcher is ruthless. He doesn’t simply demand perfection; he exploits Andrew’s insecurities by making him feel that he is easily replaceable. In service of his quest, Andrew is willing to sacrifice his sanity, his happiness, his relationship with Nicole and his father, Jim. When the script arrives at the climax, a scene in which Andrew proves his worth and talent on stage— in front of an audience and Fletcher— the triumph that closes the story has a tinge of uneasiness. You wonder: Did Andrew make the right choices?

If Whiplash feels personal, that’s not a coincidence. In keeping to the screed of ‘Write what you know,’ Damien Chazelle largely drew from his time as a jazz drummer at the Princeton High School band and the suffering he endured under a teacher who, although not as abusive as Fletcher, struck him with fear and anxiety. “I definitely embellished, exaggerated, I never went through what Miles’ character goes through,” Chazelle said in an interview, “but there was a kind of visceral fear I felt or related to this teacher and then with that, you kind of ask, ‘Well, why didn’t you just quit?’ But with that fear was this equally visceral sort of need or desire to… seek their approval? Their approval became the most important thing to me in the world. And by that same token, I look back and I know I became a much better drummer than I would have minus that approval because I didn’t even go into it caring so much about drumming… Again, I have to stress that this person was not abusive the way that [Fletcher] is, but I think it kinda helped spark the idea of that dilemma for me: What if you had a teacher who was that abusive?”

Dissatisfied writing on hire for films that he did not enjoy, Chazelle wrote a first draft of Whiplash in a few weeks; for a year, he tinkered with it before sending it out in to the world. It wasn’t just that the initial draft was messy; its author felt a little embarrassed putting his experience on paper. But he also had to write it, namely in response to his failed attempt at raising interest in his modern musical idea, a story he called La La Land. He decided it might be worth his while to write something “smaller” and more realistic.

And Whiplash is a small story. The locations are limited largely to the music room, or other small spaces (a living room, bedroom). The cast is minimal—apart from Andrew and Fletcher as leads, the two main supporting characters are Jim and Nicole. Others, such as Andrew’s drumming competitors, Carl and Ryan, as well as his aunt, uncle, and cousins, only have brief appearances. That’s about it. For the most part, this is a two-hander between Andrew and Fletcher. Two sides of the same coin. A coin called chasing greatness.

Fletcher understands what it takes to be great. His approach is less than ideal, but that’s because he believes true potential can only be coaxed out under extreme pressure. Andrew, in spite of the abuse and torment, continues to stay because he realizes that Fletcher is the only other person who understands what it means to chase greatness.

Meanwhile, Jim embodies everything Andrew fears of becoming— an unsuccessful writer with nothing to show except a failed marriage, bowed and beaten down by life. He lets his brother make fun of him at dinner…

… and when somebody bumps a popcorn bucket on his head at the cinema, Jim is the one who apologizes.

But what Andrew may not understand either is that a life dedicated to greatness can be lonely. Consider scenes 27 to 38. A montage of Andrew pushing himself at the drums, contrasted with Fletcher’s lonely life in an empty apartment and a frozen dinner. A photo hints at a wife and child; we can put two and two together and understand what happened.

But then, consider how Fletcher reacts when he puts on a jazz record. Consider how much music means to him. It makes you wonder: does he believe the sacrifices he made were worth it?

By the end of Act 1, Andrew has gotten a taste of Fletcher’s teaching style— and decided to stick it out. Again, it’s a conversation with his father that prompts him to stay…

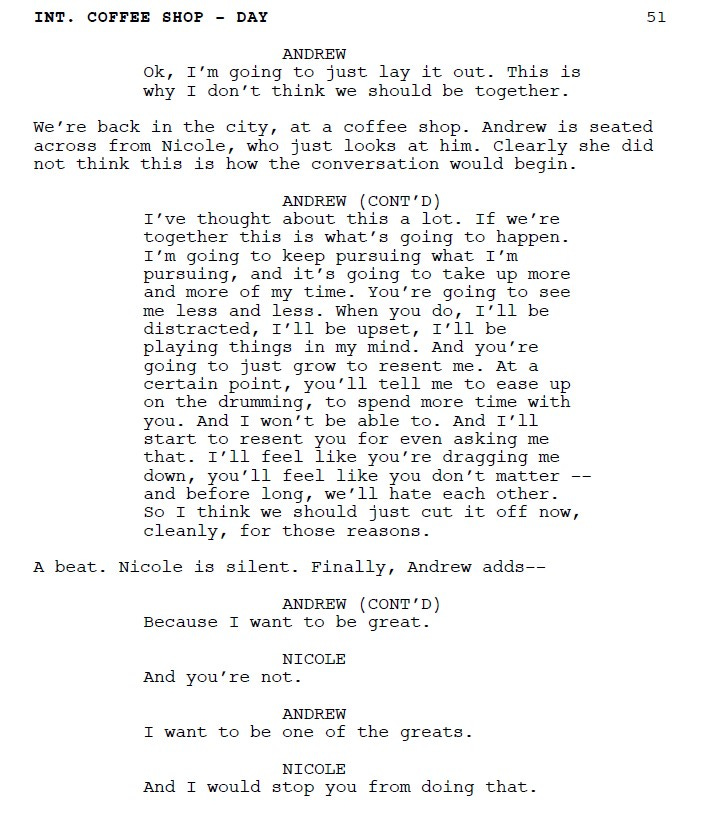

Act 2 charts Andrew’s slow rise to improvement, though it seems to chip away at his humanity little by little, as evidenced by a family argument in Scene 50…

… followed immediately after by his break-up with Nicole.

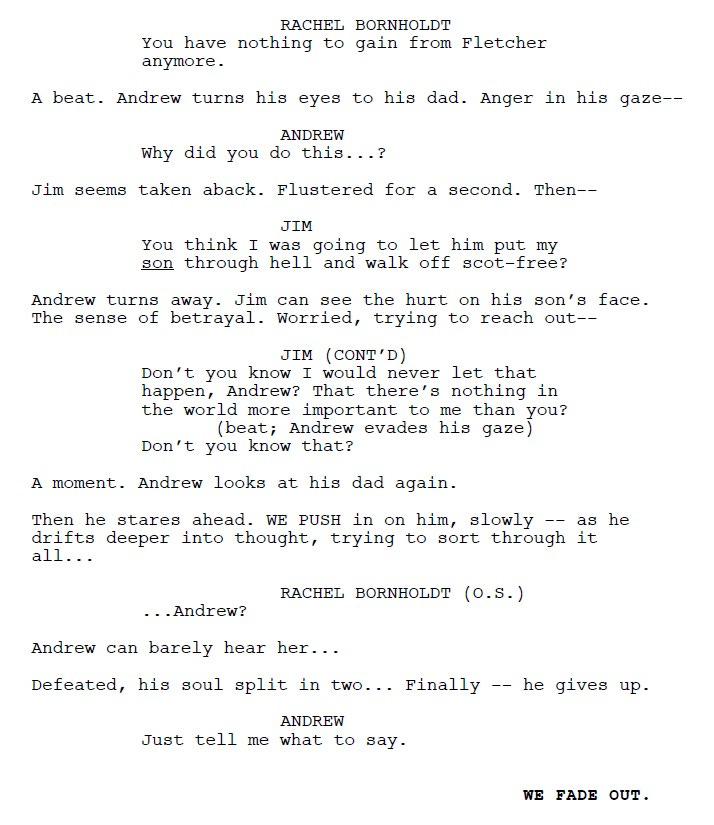

Fletcher only stokes Andrew’s doubts when he brings in Ryan, Andrew’s classmate, and jeopardizing the little ground and favor he thought he’d gained. Act 2 finally concludes with Andrew at his lowest point, when he attempts to play on stage with a broken finger, failing to even get a little support from the other drummers, and almost beating up Fletcher. Expelled from Shaffer, with nothing to lose, he agrees to give the complaint that will tip a potential lawsuit in their favor to get rid of Fletcher.

Act 3 picks up months later, hinted at being six months or so. Andrew has stopped playing drums, works in a sandwich shop, and no longer visits the cinema to watch old movies with Jim. A shell of his former self. But an encounter with Fletcher, fired from Shaffer, leads to an unexpected invitation to play with Fletcher’s band at a jazz festival. Andrew’s spirits rise a little. But not for long. Fletcher, knowing it was Andrew who complained, has set the boy up for public humiliation by playing a different piece instead of what Andrew had practised.

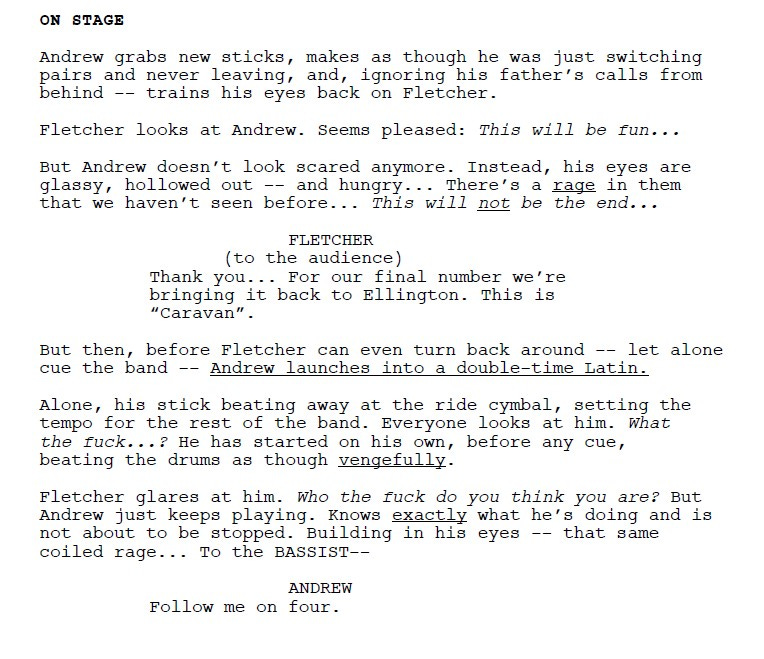

And that leads to the most disturbing part of the story; the one where Andrew makes a choice to rise to Fletcher’s level. He returns to the stage and his drums, and rebelliously starts on his own. With no choice but to follow, the band joins. Fletcher could murder him, and probably plans to the moment the music stops. Andrew couldn’t care less. He’s giving Fletcher a taste of his own medicine.

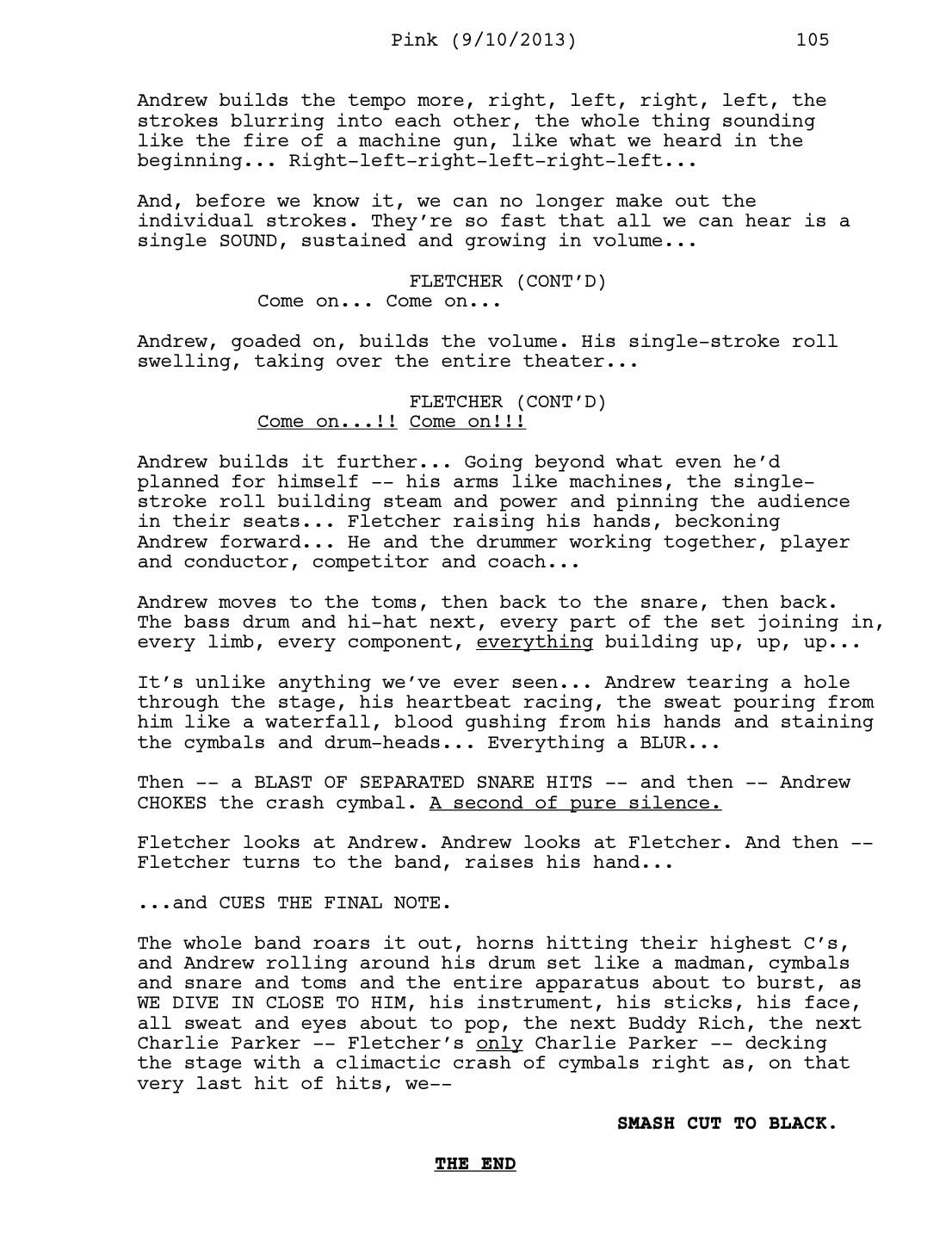

But something unexpected happens. Andrew begins to play— and I mean, really play. It gets Fletcher’s attention. It gets the audience’s attention. And it certainly gets our attention. Fletcher’s fury turns into a grudging respect. When the song is supposed to end, though, Andrew continues. He’s reaching for the level of the greats— and he’s getting there. Fletcher cannot believe it.

And on page 104, Fletcher is there to help Andrew. First by steadying his crash cymbal, then by guiding Andrew towards the final note. After all that abuse and torment, the two are working together; creating something incredible together. The screenplay opens with Andrew failing to impress Fletcher with an impromptu audition; it ends with Andrew becoming a drummer great enough to impress Fletcher.

But at what price has Andrew won?

Chazelle couched this unusual story about the relationship between a teacher and his student in the confines of a thriller genre for two reasons.

Reason Number One: It made the story more attractive to investors versus playing it as a straight drama.

Reason Number Two: It made the story more appealing to audiences because they understand genre, drawing from his experience writing horror films on assignment to create atmosphere and tension.

Lesson: When you want to tell a story that is tonally unfamiliar, it pays to use a familiar genre to make it more palatable. Whiplash couches a drama within the Trojan Horse of a thriller. Christopher Nolan did something similar when writing Oppenheimer, framing a biopic within the confines of a superhero origin story, a heist thriller, and a courtroom drama.

The Whiplash screenplay is 105 pages long, and contains 108 scenes. Many of these scenes are brief and have no dialogue. Chazelle is very visual in his writing: crisp, descriptive, but not overly done. This is especially true when he’s describing the action or introducing a character.

He also paid careful attention to the dialogue, aiming for a “really musical and percussive and rhythmic” feel to complement the subject at hand.

Likewise, the pacing is tight, a result of Chazelle trimming the initial 130 pages to 100 pages, turning the screenplay into a lean, mean, heat-seeking read. When he worked on the initial drafts, Chazelle began with the first and final images of the story (hence why the opening and closing scenes feel like mirror images), then worked his way backwards.

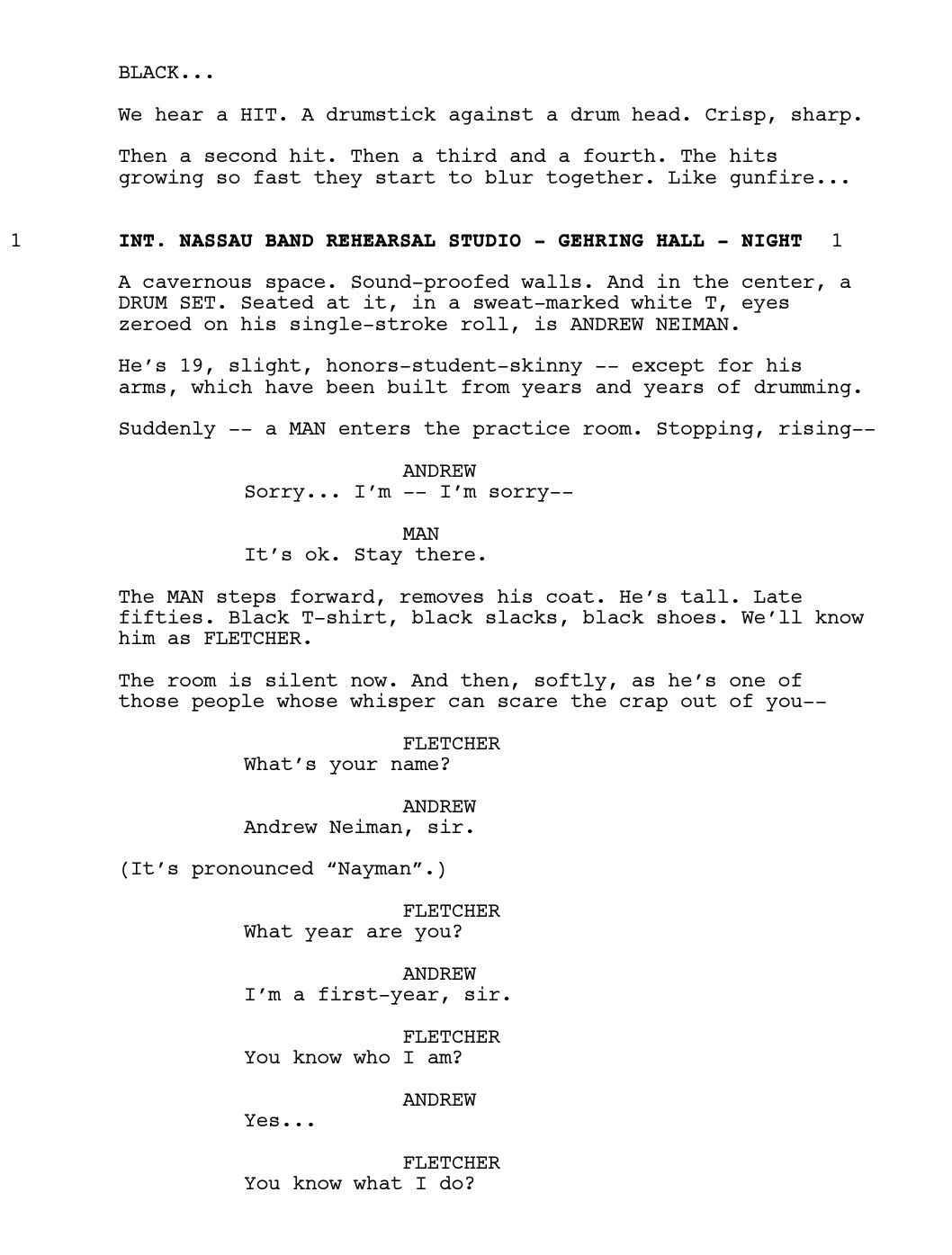

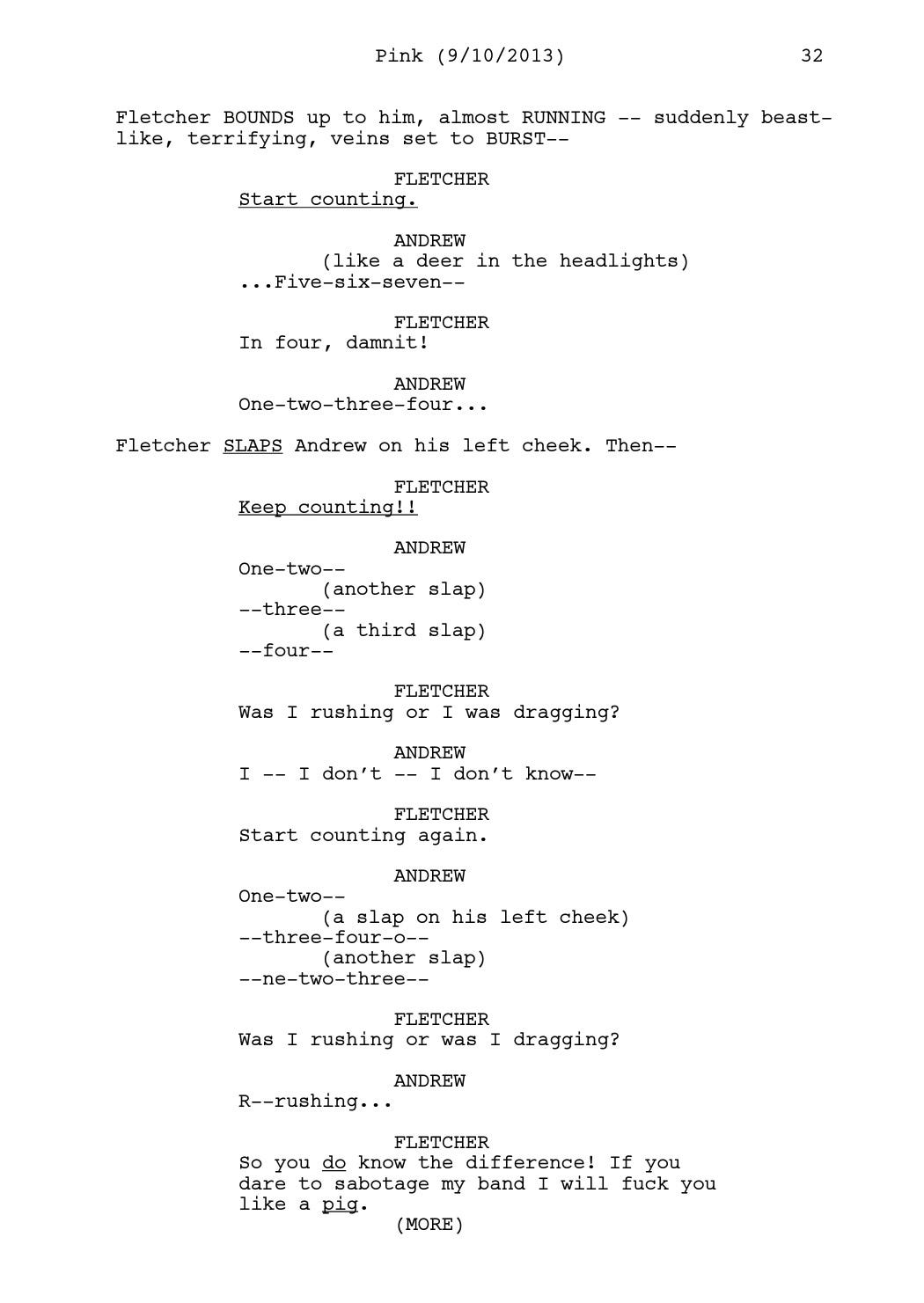

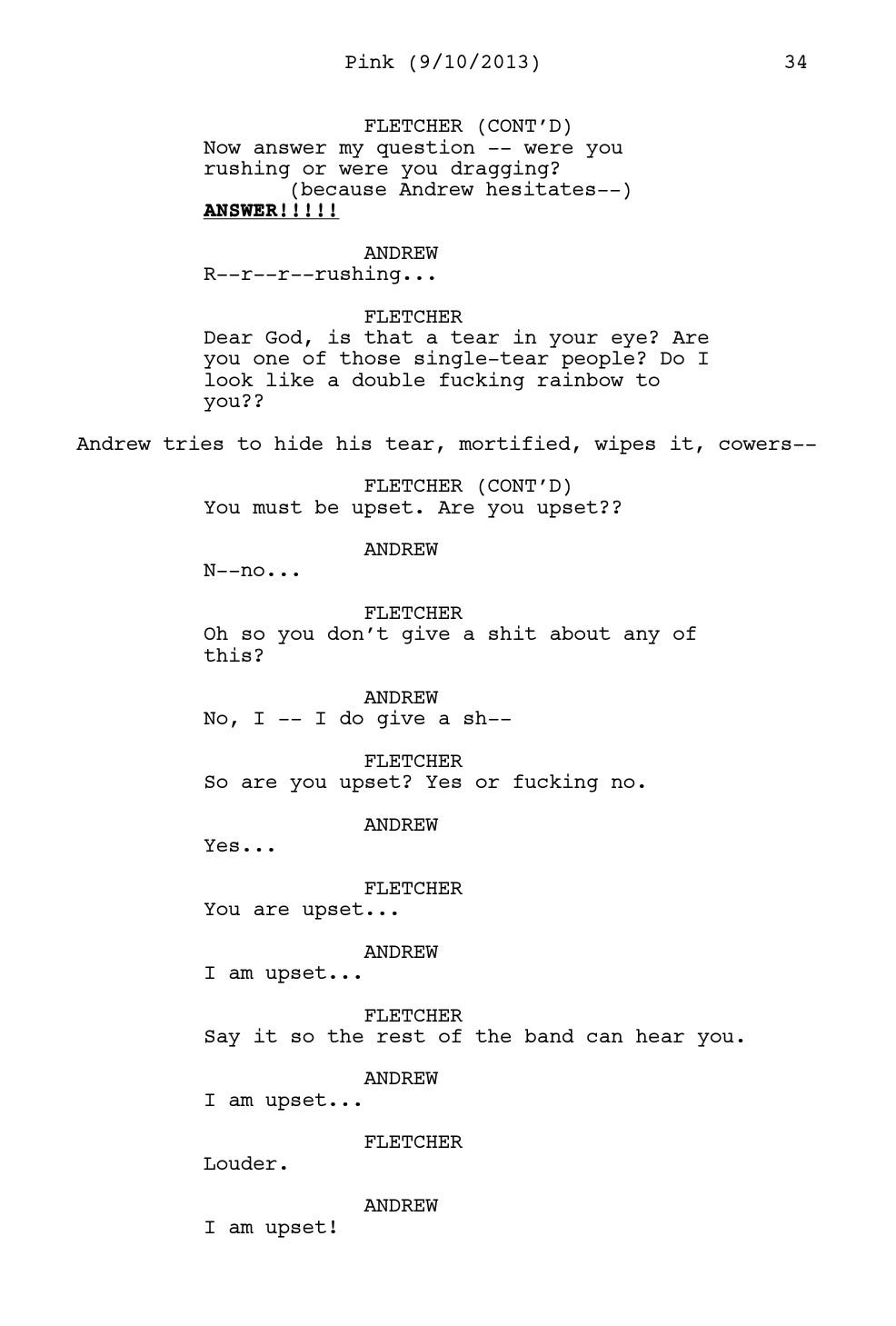

Another thing that is important, though most likely not deliberate at the outset, is to have one scene that encapsulates your entire script. In Whiplash, that is Scene 23— where Andrew gets first-hand experience of Fletcher’s explosive style of instruction. When everyone passed on picking up the script, despite making the 2012 Black List, it was Jason Reitman (Juno) who recommended Chazelle to shoot one scene that could be used as both a short film and a proof of concept; and it was that scene (refer to the above screenshots). The gambit paid off— the short film won the Sundance Jury Award in 2013, the producers were able to secure the funding that was previously denied to them, Chazelle made his film, and Whiplash got nominated at the Academy Awards for Best Adapted Screenplay (instead of Best Original Screenplay).

Chazelle’s efforts offer some unusual yet valuable lessons. Like many aspiring writers, he used his personal experiences— in this case, a traumatic one— to write something that he knew; but he used the familiarity of a genre to smuggle in a story that, had it been played straight, was too unusual. In Whiplash, it turns into a delirious and troubled journey into the rise of an aspiring artist. As Chazelle has personally discovered, it’s not a bad way to launch a career.

Notes:

Ford, Rebecca (December 9, 2014) | Making of ‘Whiplash’: How a 20-Something Shot His Harrowing Script in Just 19 Days (The Hollywood Reporter)

Newman, Melinda (February 5, 2015) | ‘Whiplash’ Screenplay: That Touch of Horror Made Chazelle’s Script Sing (Variety)

Dowd, A. A. (October 15, 2014) | Whiplash maestro Damien Chazelle on drumming, directing, and J.K. Simmons (A.V. Club)

Hammond, Pete (August 30, 2016) | Damien Chazelle’s ‘La La Land’, An Ode To Musicals, Romance & L.A., Ready To Launch Venice And Oscar Season (Deadline)

Richlin, Harrison (September 20, 2024) | ‘Whiplash’ at 10: Damien Chazelle and Miles Teller on Their Breakout Hit and How It Remains a ‘Barometer’ for Their Work Today (Indiewire)

Behind the Curtain (March 6, 2020) | How I Wrote Whiplash (Writing Advice from Damien Chazelle) (YouTube)