Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017) Script Review | #80 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Martin McDonagh turns a woman's crusade to get justice for her dead daughter into an acerbic, funny, and crushing screenplay.

Logline: After seven months have passed without a culprit in her daughter's murder case, Mildred Hayes makes a bold move, painting three signs leading into her town with a controversial message directed at Bill Willoughby, the town's revered chief of police. When his second-in-command Officer Jason Dixon, an immature mother’s boy with a penchant for violence, gets involved, the battle between Mildred and Ebbing's law enforcement only gets exacerbated.

Written by: Martin McDonagh

Pages: 83

Number of scenes: 134

With his third feature screenplay, Martin McDonagh has emerged as one of the most exciting and original voices in cinema, and he is here to stay. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is sharp, caustic, brilliant, and devastating, sometimes all at the same time.

The premise is simple: Mildred Hayes, a middle-aged woman living in the fictional town of Ebbing, rents out three billboards to post a controversial message that gets the police chief’s attention. Mildred is aggrieved that the police haven’t caught her daughter’s murderer and rapist yet. Police Chief Willoughby is incredulous and feels unfairly maligned because they were unable to trace the killer through the DNA (implying that it was either someone passing through the town or someone who has never entered into the criminal database); he’s also dying of pancreatic cancer. His second-in-command, the racist and partially dim-witted Officer Jason Dixon, is incensed on his boss’s behalf; when Mildred refuses to take the boards down, he goes after Mildred’s friends, then the billboard renter himself.

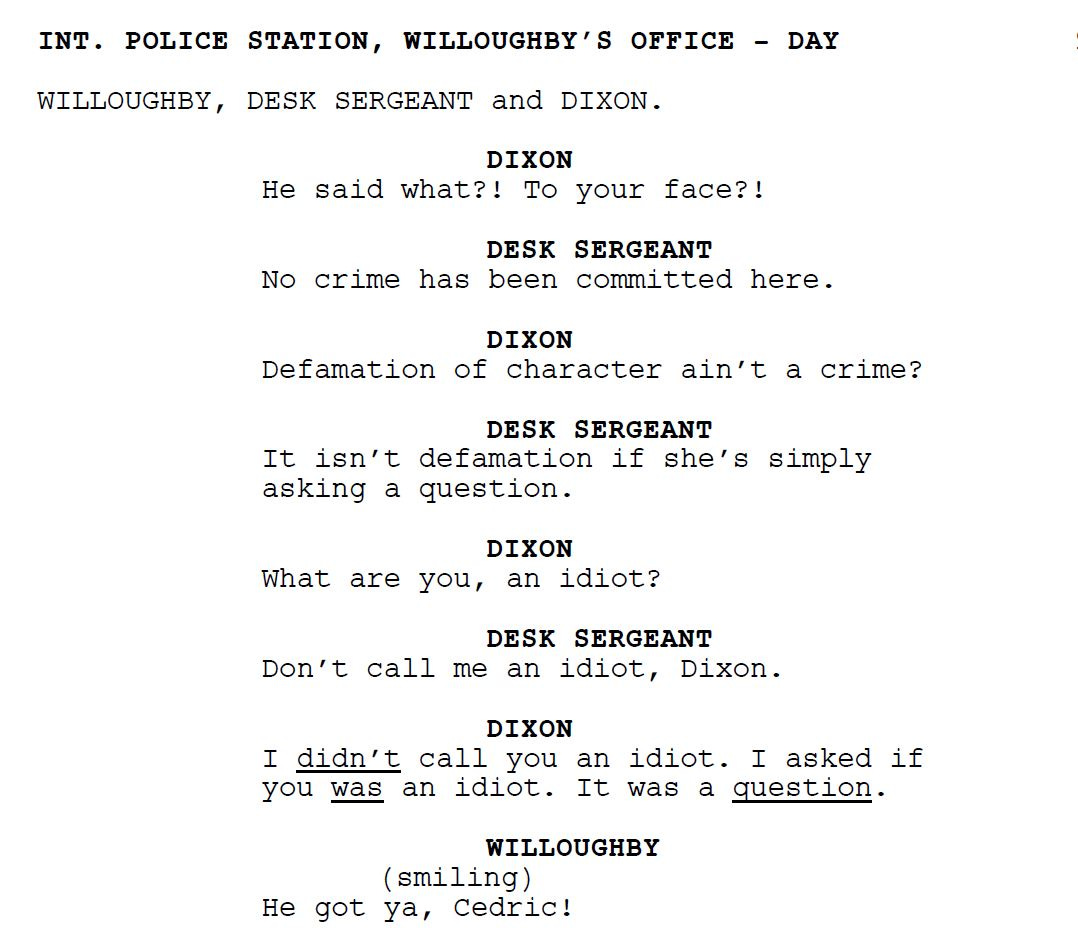

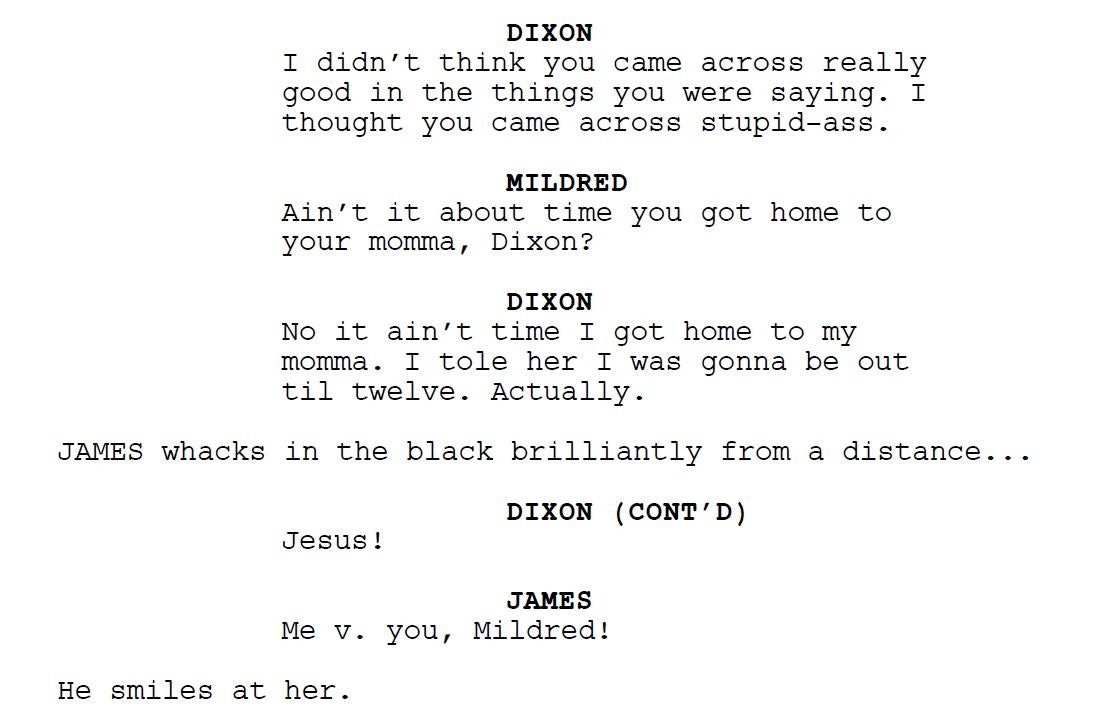

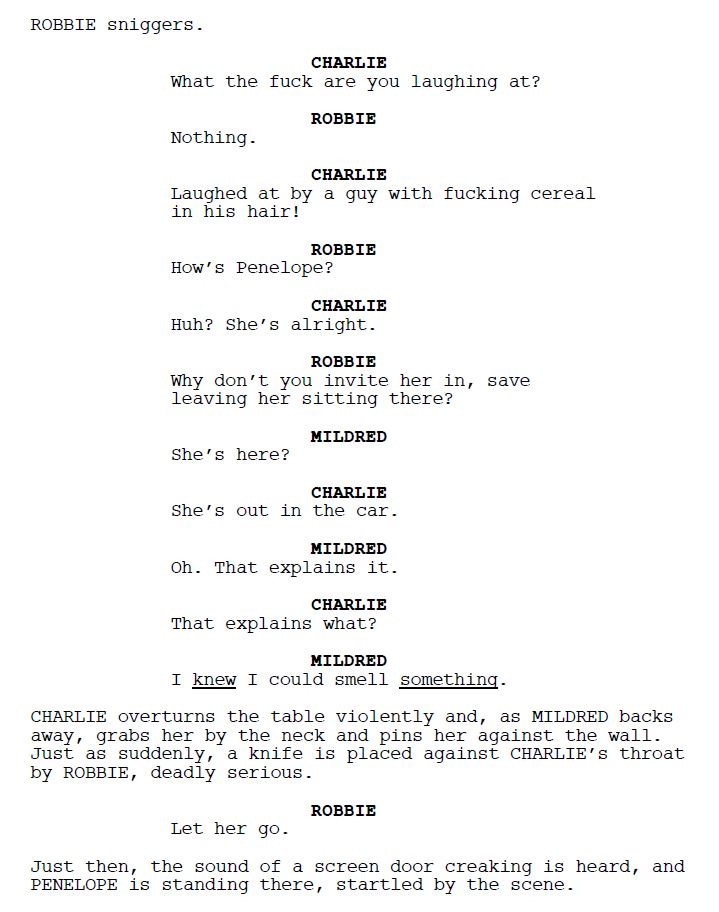

Mildred, Dixon, and Willoughby are the trio at the heart of this mad dance. A subject this grim has no right to be this funny but I was laughing all the way to the end of the screenplay. McDonagh has a knack for finding veins of humor when mining the ore of dark subjects; he turns conversations into unexpected directions (simultaneously using it to reveal the personalities of his characters), and owing to his gift for writing brilliant dialogue, the verbal exchanges in his scripts are a delight to read. For the actors, it must feel like manna from Heaven.

When McDonagh sat down to write Three Billboards, he didn’t have a plot in mind; all he had was the image of the three billboards in the title. The image originated when McDonagh was on a trip in the United States sometime in the late ’90s, spotting three small signs off the I-10 near Vidor, east of Beaumont, which stated:

‘Vidor Police Chief Botched Up the Case’

‘Waiting for Confession’

‘This Could Happen to You’

The image of the signs stayed burned in his mind as he worked on the script (ten years before it was made into a film and ten years after that trip). He surmised that whoever put up those signs had a lot of nerve and a lot of anger and thought it was put up by a mother (hence, why his main character became Mildred Hayes). In actuality, the Vidor signs were done by a James Fulton, after his daughter, Katherine Fulton Page, was found murdered in a car accident in May 1991. Fulton and the family believed Page’s ex-husband, Steve Page, was the murderer and that the Vidor police bungled the case. The signs, it seems, are still up there, even two decades later. Like Mildred, it seems Fulton won’t back down until justice is delivered or until he’s dead.

Lesson for the aspiring screenwriter: Take your nose out of the phone and pay attention to the surroundings around you (especially if they are new), for the world is filled with potential seeds of stories— you only have to be attuned to catching them.

McDonagh is not a fan of screenwriting formulas. Rather, he prefers to discover where his characters will take him, once he has established the central conflict. That explains why his scripts tend to take unexpected turns and feel unconventional. But study closely the machinations and you’ll notice that even McDonagh’s stories tend to follow a trajectory that is ultimately found in a screenwriting formula! There’s a beginning, there’s an inciting incident, there’s a midpoint, a low point, the build-up, the climax, and the finale. The difference is that rather than taking a top-down approach (for instance, wondering what should happen at the halfway point), McDonagh works from the bottom-up: He puts his characters into uncomfortable, challenging situations, and then keeps escalating. Guess what happens when you do that? Your story tends to take the structure found in a formula!

Lesson for the aspiring screenwriter: Screenwriting formulas are like recipes; even if you follow it to a tee, there’s no guarantee that you’ll end up with a good screenplay. The formula is only a reminder that you:

Need to put your characters into difficult situations that they need to get out of;

Need to keep increasing pressure on the characters.

For instance, the unexpected suicide of Chief Willoughby at page 44 is the screenplay’s Midpoint, and while killing one of your main characters isn’t ideal, it represents a shift in sentiment: In the first half, there was support for Mildred; in the second half and in the wake of the police chief’s death, Mildred faces opposition.

When does a formula become apparent or blatantly obvious? It happens when the plot dictates your characters’ actions instead of your characters driving the plot, and it happens when your characters’ personalities or fortunes (or misfortunes) undergo a 180-degree radical change. If your protagonist starts as a coward, they must become Rambo by the end. It sounds absurd, but most Hollywood fare tends to suffer this fate. McDonagh understands that people don’t change overnight; by the end of Three Billboards, Mildred and Dixon change only to a small but believable degree. Mildred mellows a little without abandoning her anger and grief; Dixon demonstrates a little intelligence to cleverly get a suspect’s DNA when he’s no longer a cop, and shows some sign of growth when he proposes going after a murderer to deliver justice on behalf of Mildred’s daughter. That’s why it feels believable, because that’s how people change in real life.

Let’s take a hypothetical scenario. Imagine you are writing a story about an estranged son seeking to reconcile with his father. The Hollywood version would end with a lot of tears and confessions and “I love yous” that kicks the melodrama factor up to 11. Instead, end it with the two characters taking that first step to reconciliation. If the son never listens to his father’s opinion, let him choose to listen at the end. If the father has a habit of criticizing all that his son does, let him not criticize at the end.

Lesson for the aspiring screenwriter: Make your characters grow in believable ways, and your screenplay will be even better for it.

Owing to his prowess for crafting fantastic dialogue, McDonagh automatically finds himself in the same class as Aaron Sorkin or Quentin Tarantino. But I would say that although McDonagh writes good dialogue, he is also more visually driven and finds ways to communicate powerful moments using silence or little dialogue. Take, for instance, the scene when Mildred remembers her last conversation with her daughter, Angela:

Sometimes, the exchange is pared down to the bare essentials, just a line or two, that speaks volumes:

The point being that McDonagh is far more restrained than Sorkin or Tarantino, while also having the advantage of keeping his characters grounded and realistic (at the same time they are delivering the most outrageous lines):

Like many screenwriters, his character descriptions are restricted largely to their ages, and perhaps the rare additional detail. Interestingly, he wrote the roles of Mildred and Dixon for Frances McDormand and Sam Rockwell (the latter with whom he worked on Seven Psychopaths) respectively; but it is advisable to only write roles for specific actors AFTER you’ve proved yourself!

The screenplay only runs for 83 pages, but that’s because McDonagh hits the ground running. Mildred kicks off the inciting incident (renting the billboards) by page 2 itself…

… and we get the backstory in bits and pieces through the exchanges, maintaining tension and keeping us engaged.

Lesson for the aspiring screenwriter: You don’t have to wait until page 15 to insert the Inciting Incident—the earlier you start, the faster your story will move.

When Three Billboards came out in 2017, some circles mistakenly claimed that the story was a response to the Trump Administration in its depiction of the fictitious small town and especially the character of Dixon (you just know that Dixon and most people in Ebbing, Mildred included probably, would have voted for Trump); but McDonagh denied and pushed back against the claims, pointing out that he wrote Three Billboards years before the 2016 election. He conceived the town as a character in its own right by traveling around America for a while to get a feel for what a small town is like. Location has always fascinated McDonagh; he’ll even set stories in places he’s never been to! (His Irish plays take place on islands he’s never visited). After all, his first film, In Bruges (#40 on the WGA’s List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century) entirely took place in Bruges.

The other pushback came due to the character of Dixon. It’s understandable why some weren’t happy about giving the racist momma’s boy character a redemption arc, when he saves the Angela Hayes casefile from going up in flames (by a fire caused by Mildred); but McDonagh did so deliberately to uncover the humanity underlying the stock types of ‘Good Cop’ (Willoughby), ‘Bad Cop’ (Dixon) and ‘Grieving Mother’. Stories aren’t meant to have characters who all think politically correctly and ideologically similar. There’s a word for those kinds of stories: propaganda.

Three Billboards is a stellar screenplay; the rare character-centric story that marches to its own beat. Had it come out in any other year, it would have won McDonagh the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (it lost to Get Out). Still, McDonagh should take solace in the knowledge that this screenplay will be studied and read many times in the years to come. It makes a great case study for aspiring and established screenwriters to learn from.

Notes:

Darling, Cary (March 1, 2018) The Texas connection behind ‘Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri’ | The Houston Chronicle

Utichi, Joe (January 8, 2018) Golden Globe Winner Martin McDonagh On ‘Three Billboards’, Strong Women, And Why Formulas Are “F–king Boring” | Deadline