The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) Script Review | #63 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A cheerfully obscene and electric biography of Jordan Belfort filled with money, fame, drugs, sex, and scandal.

Logline: The story of Jordan Belfort, from his rise to a wealthy stockbroker living the high life to his fall involving crime, corruption, and the federal government.

Written by: Terence Winter

Based on: The Wolf of Wall Street by Jordan Belfort

Pages: 137

Scenes: 248

The Wolf of Wall Street is so cheerfully depraved and unhinged that, according to the people who actually lived through the events, it doesn’t even begin to compare to how cheerfully depraved and unhinged it really was. Reality, it seems, will always be weirder than fiction.

And did I mention that it’s also outrageously funny? You wouldn’t expect a sensational true life story involving corruption and fraud to be humorous but it is. That was a deliberate choice by the screenplay’s writer, Terence Winter, who adapted the book of the same name by Jordan Belfort; he wanted to preserve the main character’s charm so that we, like the many people who were seduced by his charisma, would be swept into the orgy of excess and his Bacchanal lifestyle until the carousal stopped, the dream ended, and you woke up to realize you’d been hoodwinked.

Who are the characters in The Wolf of Wall Street?

Jordan Belfort – “handsome, 30”

Naomi Lapaglia– “24, blonde and gorgeous, a living wet dream in LaPerla lingerie”

Donnie Azoff – “preppy-looking, 25, with horn rims and bright white teeth”

Patrick Denham – FBI agent

Jean-Jacques Sorel – 30s, suave”

Aunt Emma – “50s, demure, British”

Teresa Petrillo – Belfort’s first wife

Max Belfort

Janet – Belfort’s assistant

Chester Ming

Robbie Feinberg

Alden Kupferberg

Nicky Koskoff

Brad – “muscular and bald, with a Fu Manchu mustache”

Chantalle – “a bombshell in panties, bra and sneakers”

Mark Hanna – “30s, charismatic, movie-star handsome”

What is the screenplay structure of The Wolf of Wall Street?

At 138 pages, the screenplay moves brisk and efficiently, setting the tone and pace of what is to come. It’s impressive in the way it manages to cram over a decade of story in such a short page count, starting from Belfort’s humble beginnings as a lowly ‘connector’ at L.F. Rothschild in 1987 and ending at the turn of the millennium with him in prison… only to hint that after he got of prison early, he got rich again as a motivational speaker in the early 2000’s.

What this means is that the script has little description and LOTS of dialogue— while still fitting within the confines of a Three-Act structure. No, really, it does.

Act I – pages 1-33 – A flashback to Jordan Belfort climbing up the ladder and his first marriage

Act II – pages 33-120 – Jordan’s rise, his second marriage, the SEC and FBI on his trail, culminating in a change of life and his arrest

Act III – pages 120-138 – Jordan’s fall, his plea bargain, his divorce and arrest

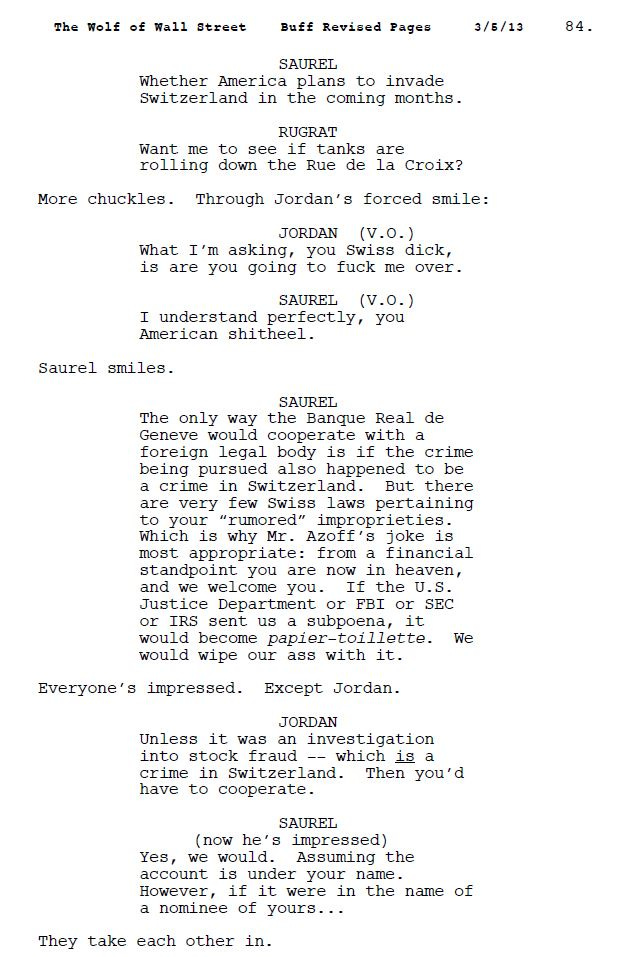

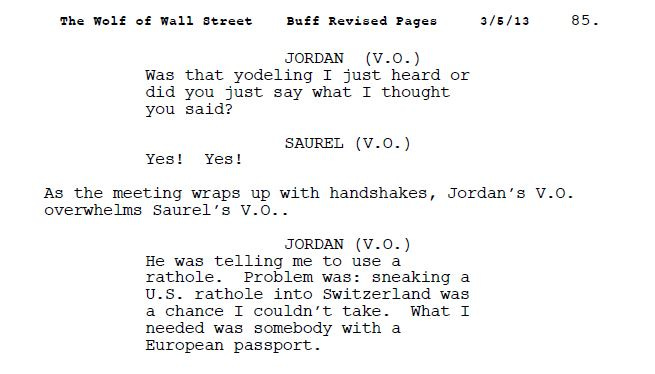

What surprises me is how Winter neatly fits the events of Belfort’s rise and fall into a structure that works for a feature film, while packing in a lot of characters and events. He is successful largely in part to a screenwriting device that most screenwriting gurus advise against, or if required, to use sparingly: voice-overs. From start to end, Belfort’s voice-over carries us through the dizzying and complex finance world, providing context and background on a lot of what’s going on so that the actual dialogue in a scene can focus on the events at hand. On top of which it breaks the fourth wall on occasion to address the reader, and on another occasion, ropes in a second voice-over for just one scene:

The Wolf of Wall Street doesn’t just break the rule on how to use voice overs in a screenplay— it rams it down, runs it over, and for good measure, runs over it again. In a way, it captures the spirit of Belfort perfectly: As a merciless rule breaker who dares to push the limits— and breaks through it.

The voice-over also has another effect: It makes us complicit. You read the screenplay because you are charmed; you watch the filmed version all the way to the end, no matter is thrown at you, because you are hooked, and you are having a good time. It’s one way to keep us engaged, even and especially on the page.

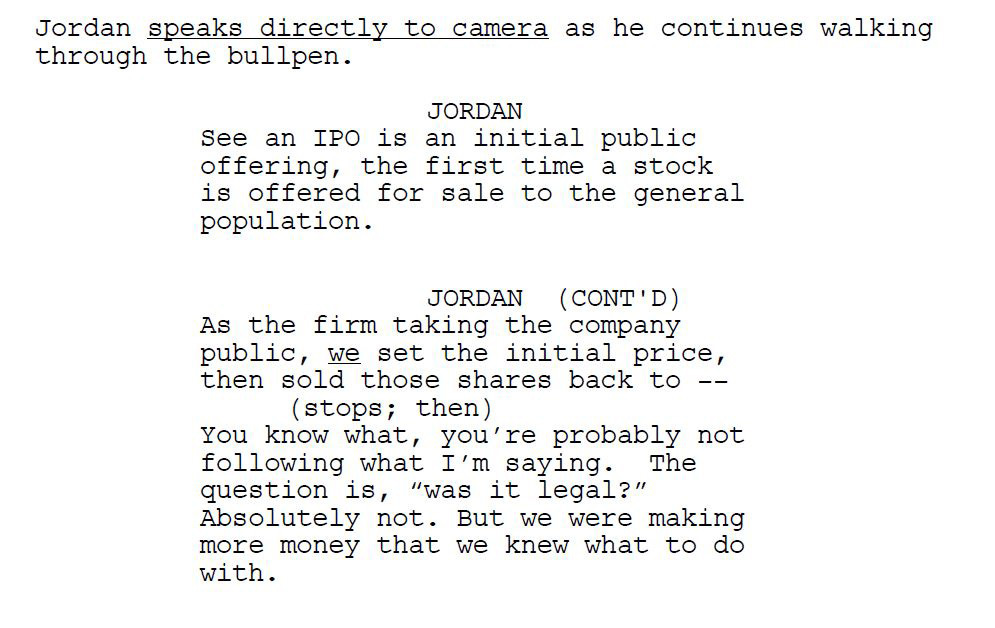

Additionally, the voice over helps to resolve the amount of technical exposition required. When Belfort talks about blue-chip stocks and penny stocks, he explains it in a way that helps you to understand just enough without it going over your head. In fact, at one point, he stops explaining to say he knows it’ll go over most people’s heads anyway:

Fun fact: Terence Winter worked in the equity-trading department at Merrill Lynch in 1987, and was present on Black Monday. His familiarity with the financial world was a great asset in the script and helping Scorsese and the team understand this world. If you want to create a world people don’t know about, either work in it or become an expert in the subject!

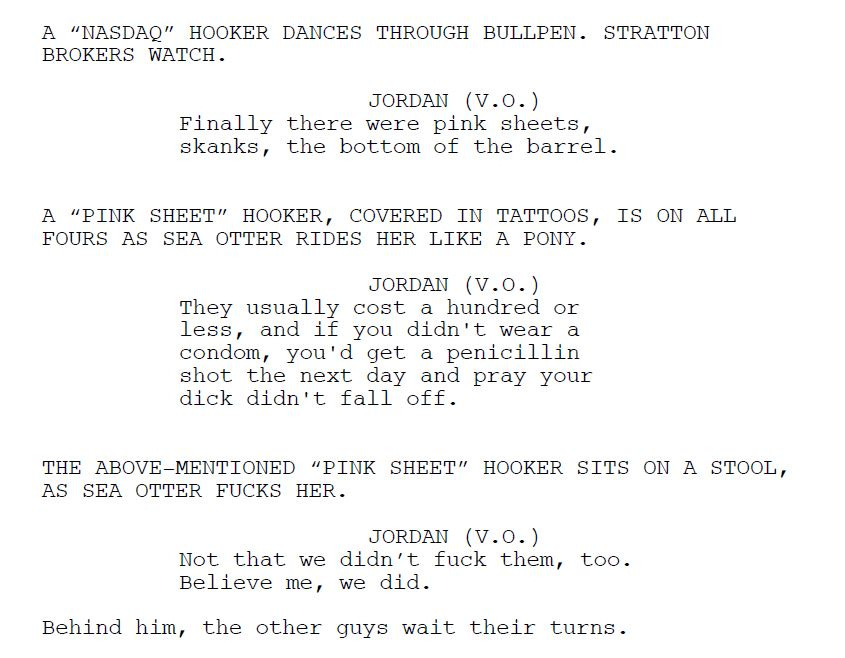

The point is that you need enough detail to show it impacts the overarching trajectory of the screenplay and its outcome. Sometimes, it emerges in an amusing way, such as Belfort describing the types of prostitutes they hired by ranking them according to the type of stocks traded on the Stock Exchange:

These small details allow you to buy into the world. If you can believe a man could fly in Superman, then you can believe that Belfort made a lot of illegal money for himself and his friends in The Wolf of Wall Street.

The challenge in this kind of story, however, is finding the humanity within these characters— because Belfort and his crew are, well, to put it mildly, not very great people. If you see Belfort as a villain, you wouldn’t be interested in reading the rest of the story (if you see Belfort as a hero, you’ve got problems!). Winter, who polished his craft on shows like The Sopranos and Boardwalk Empire, knows a thing or two about finding something human in the worst of people. He doesn’t believe the world is divided into heroes and villains; people aren’t all good or all bad; and even the worst person may have some humanity. That’s what you—the writer—are supposed to find.

How accurate is The Wolf of Wall Street?

That depends. For starters, apart from Belfort, all the other characters have their names changed (like that of Naomi) or they are a composite of characters (as in the case of Donnie Azoff). Winter isn’t a stickler for historical accuracy in this kind of story, and I agree: As long as the liberties you take with changing a story doesn’t alter the narrative in a completely different direction, a writer should have the freedom to tell the story to suit the medium… as long as it is true to the spirit and emotional truth of the original material. The real person on whom Naomi is based on recently alleged that Belfort was emotionally and physically abusive, traits that don’t turn up in the screenplay; yet, does it surprise you that Belfort could be that?

The screenplay— and the resulting film— feel like a companion piece to Goodfellas, a comparison that is not accidental. When Martin Scorsese came onboard, he knowingly agreed that it would be in a similar vein to his gangster epic (incidentally, Belfort’s origins would have started around the time that Henry Hill went into Witness Protection).

Writing a screenplay as sprawling and challenging as The Wolf of Wall Street is not easy. It takes an experienced hand or a talented writer to strike the right tone. Even then, Scorsese and his team would add details while filming that don’t appear in the script- which explains why the film runs nearly 3 hours while the screenplay is 138 pages.

Who is Terence Winter?

Terence Winter (born October 2, 1960) is an Emmy-award winning and Oscar-nominated American screenwriter and producer. Winter began his career as a writer for various television series in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including Sister, Sister, and Xena: The Warrior Princess. His breakthrough came with his involvement in the critically acclaimed HBO series The Sopranos, where he wrote or co-wrote 25 episodes, including the famous “Pine Barrens” episode.

Winter went on to create Boardwalk Empire for HBO, a series that delved into the Prohibition era and organized crime, serving as head writer, and executive producer. Prior to The Wolf of Wall Street, his previous feature film screenplays were Get Rich or Die Tryin’ and Brooklyn Rules.

If you’ve got plenty of fast-paced dialogue, keep your descriptions to a minimal, and build momentum without stopping, and always— always!— keep the focus on your main character if they’re morally ambiguous; the moment you let outside views in, you’ll destroy the effect. We love The Godfather and feel for Don Corleone because we see him as a wise grandfather-type of character, instead of the ruthless mafia don he is. The same goes for Goodfellas. Likewise, by keeping us in Belfort’s world, we are prevented from seeing how he thrives at the expense of defrauding millions of people. That would take the wind out of the story’s sails, I can tell you that.