The Master (2012) Script Review | #84 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A surprisingly inert script from a filmmaker whose work is anything but, The Master is underwhelming when taken together as a whole.

Logline: A Naval veteran arrives home from war unsettled and uncertain of his future - until he is tantalized by the Cause and its charismatic leader..

Written by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Pages: 125

Reader, I did not like the screenplay for The Master. I found it disjointed and flat; a sum of parts that never completely add up together. But worst of all, and I do not say this lightly, I was bored. And this is the first Paul Thomas Anderson screenplay I’ve found boring.

According to its logline, The Master follows is set in post-World War II. The main character, Freddie Sutton, is a wild and damaged veteran who has returned to California following his stint in the Pacific. Freddie is an alcoholic who brews moonshine; violent and sex-obsessed, he drifts aimlessly until he runs into Lancaster Dodd or ‘the Master,’ the charismatic leader of a new religious organization simply called The Cause. And then… things happen. It’s disturbing, but vague; nothing completely comes together, and the result is dissatisfying. Not that I expect feel-good endings, but I felt cheated by the entire thing, like it was all smokes and mirrors.

I’ll give Mr. Anderson this much: his screenplays are never predictable. If they follow the rules of conventional drama, if there is a structure, it is buried and hidden from sight. You’d have to read the script or watch the movie a few times before you can discern it. The result is a story that feels different and unique, and it’s what makes Mr. Anderson such an exciting filmmaker in the first place. But structure matters. Which is why Mr. Anderson’s admission that he had “no idea what [The Master] was, where it was going, or where it would end up,” makes sense. Some scenes emerged from unused early scenes for There Will Be Blood; some were based on war stories told to him by Jason Robards (who’d worked with him on Magnolia) about his drinking days in the Navy; others, such as Freddie’s experiences as a wanderer and migrant field worker, were taken from the life of John Steinbeck. An ambitious concoction on its own.

And then there’s the Scientology angle of it all. The Master is not a story about Scientology, but its titular character was inspired by its founder, L. Ron Hubbard; an inspiration that Mr. Anderson acknowledges. The parallels are much more visible in the script that is available online, which is an early version that appears to be the same one used to raise financing— Lancaster Dodd is in his mid-40s, as was Hubbard in those years; they share a love of boats and motorcycles, and a paranoia of the American Medical Association; both wrote their ultimate secrets in a book that was said to either kill or drive its readers mad (which sounds an awful lot like the basis for Monty Python’s ‘Funniest Joke in the World’ skit); both threw tantrums; and both had wives named Mary Sue. In the film, Mary Sue becomes Peggy Dodd. Other inspirations include Aimee Semple McPherson, a radio evangelist in the 1920s; Werner Erhard in the 1970s; and Jim Jones, whose followers drank cyanide-laced Flavor Aid.

Like the Freddie character, Mr. Anderson throws in and mixes so many ingredients into his scripts to brew heady concoctions; it’d be more accurate to call him an alchemist than a screenwriter. Which is why even if I didn’t like The Master, there are some things worth learning from this screenplay. Given that Mr. Anderson had two screenplays on the WGA list almost back-to-back (Phantom Thread was #86), this offers an unexpectedly unique opportunity to examine his style.

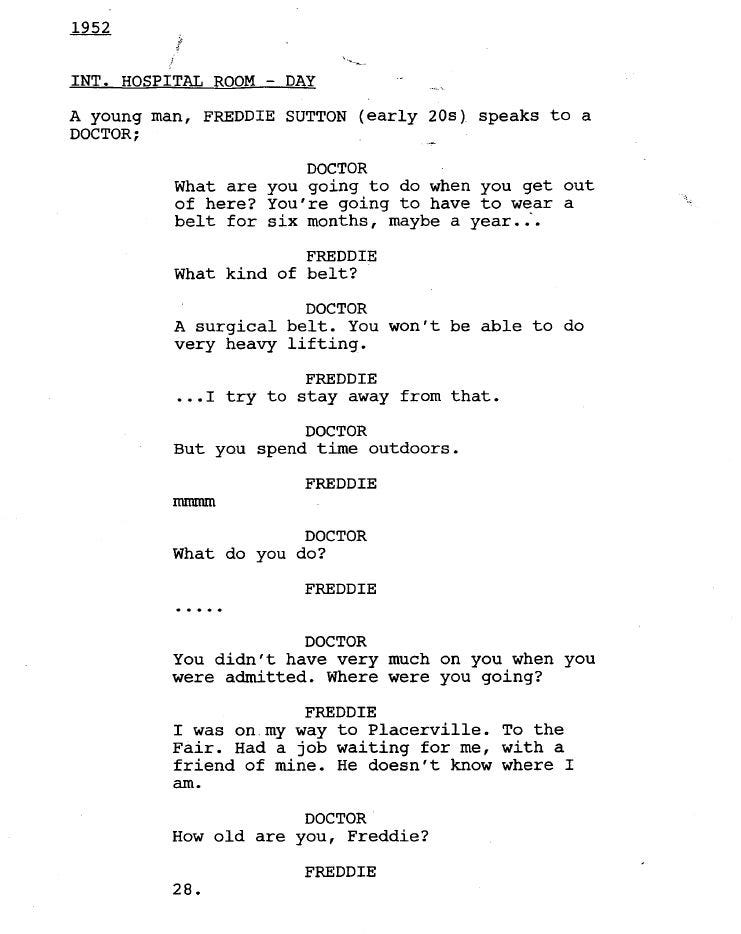

For starters, both scripts dispel with lengthy descriptions or scene-setting, and open immediately with a conversation— and with a doctor, no less. In Phantom Thread, Alma speaks with a doctor before the script flashes back to Reynolds Woodcock; in The Master, Freddie Sutton talks to a doctor in a scene that runs for nearly four pages consisting only of dialogue without any break. The effect is almost musical.

Likewise, he leaves a lot of scenes to be discovered on set and by the performers; often, it’s unrelated to the main story but adds to the verisimilitude. The end result is that Mr. Anderson can condense what might be long sequences or pages of dialogue into a sentence or two.

Later, he does the same later for what is a pivotal moment (or the inciting incident) where he indicates the dialogue is “TBD.”

This is a good shortcut to take when writing an early draft; stuck for dialogue or unsure how to go about it in a concise manner? Instead of dawdling, simply indicate what you want the outcome to be, and move forward. You can return to it in the rewriting stages.

However, a word of caution: If you take this approach with a script you want to get made (and why wouldn’t you??), this only works if you are going to work with actors who can improvise or bring a lot to the table, or you are writing specifically with an actor or actors in mind. Just as he wrote Phantom Thread for Daniel Day-Lewis, Mr. Anderson wrote the role of the Master with the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman in mind: “[Hoffman] was my first audience. I’d hand him chunks and hear what he responded to.” The actor’s feedback was invaluable, providing clarity and helping Mr. Anderson figure out that this should be Freddie’s story, with Dodd as supporting. Likewise, Mr. Anderson kept Joaquin Phoenix in mind while writing, trusting the actor to make sure his writing didn’t verge into “too literary” terrain.

The takeaway: If you want to keep your scenes brief and let the script be a guide for the actors to improvise, make sure you have a cast that is up to the task, or it will derail your picture.

The use of camera directions is also spare; much more spare than in his earlier efforts (Boogie Nights and Magnolia are stuffed with them). If you don’t want to use camera directions, that’s fine; in the example below, the line “CAMERA sees the note” could be substituted with “We see the note,” especially if you are still an upcoming writer and not established like PTA.

Who is Paul Thomas Anderson?

Paul Thomas Anderson, born June 26, 1970, (also stylized PTA) is one of the most acclaimed American filmmakers in the last few decades. After making his directorial debut with the 1996 film, Hard Eight, he broke out with his follow up, Boogie Nights (1997). All his subsequent films have been critical successes, including Magnolia (1999), Punch-Drunk Love (2002), There Will Be Blood (2007), The Master (2012), Inherent Vice (2015), and Licorice Pizza (2021). Of those made after 2000, three of them (including Phantom Thread) were included in the WGA list.

PTA is a self-taught filmmaker who began writing as a teenager, citing David Mamet, J.D. Salinger, David Rabe, Aimee Mann, and Brian Wilson as influences. He attended film school for only two days, deciding that he could learn more from director audio commentaries and technical books than film school.

The Master is more frustrating than fascinating, though it’s got some memorable moments, such as Freddie imagining slicing off the Master’s head at a talk, only for the head to keep talking—but these moments are far and few. What is its purpose? Who knows? The Master may be the least best of Paul Thomas Anderson’s filmography; and given his body of work, that is saying something.

Notes:

3 - https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-oct-12-ca-41788-story.html