The Big Short (2015) Script Review | #55 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A cautionary tale about greed and the 2007-2008 Recession told with acerbic wit and a biting sense of humor.

Logline: : In 2006-2007, a group of investors bet against the US mortgage market after discovering a series of flaws that threaten to bring the entire economy crashing down.

Written by: Charles Randolph and Adam McKay

Based on: The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine by Michael Lewis

Pages: 127

Scenes: 160

The Big Short is the other Michael Lewis adaptation to appear on this list, the other being Moneyball, but the two scripts could not be more different. While both tackled complicated topics in dense technical detail, The Big Short found a way to turn the (often) boring subject of finance into a humorous and scathing portrayal of the greed and amorality on Wall Street that caused the US Great Recession in 2007-2008, and a few people who saw it coming— and profited from Wall Street’s failure.

Across 127 pages and 160 scenes, the screenplay divides its time between three stories and characters who will never meet, but share the same goal of betting against the housing market. There’s Michael Burry, who gave up medicine to open his own hedge fund and was one of the first people who saw the crash coming. When a trader named Jarred Vennett (who is also the narrator) learns that Burry is shorting mortgage bonds, he makes a wrong call to a fund run by Mark Baum; Baum and his team— plus Vennett—form the basis of the second story. The third leg of the script concerns two small fish, Jamie Shipley and Charlie Geller, who stumble across Vennett’s brochure warning about the imminent collapse, and get their fund, Brownfield Fund, in on the shorting business through their friend, Ben Rickert.

Juggling three different plots is not easy. It requires synchronizing the beats of each plot to hit simultaneously without duplicating the information. That means some stories will get less attention than the others. The plot involving Charlie and Jamie get less time than the other two, and Burry’s sub-plot about his son’s Asperger’s Syndrome diagnosis leading to his realize that he himself might have Asperger’s ultimately gets cut from the final film, thereby reducing Burry’s plot as well. It is Baum’s section, and those of his team, that form the center of the screenplay. I suspect that’s because they work in the heart of Wall Street, and that gives them the best access to information about the impeding firestorm.

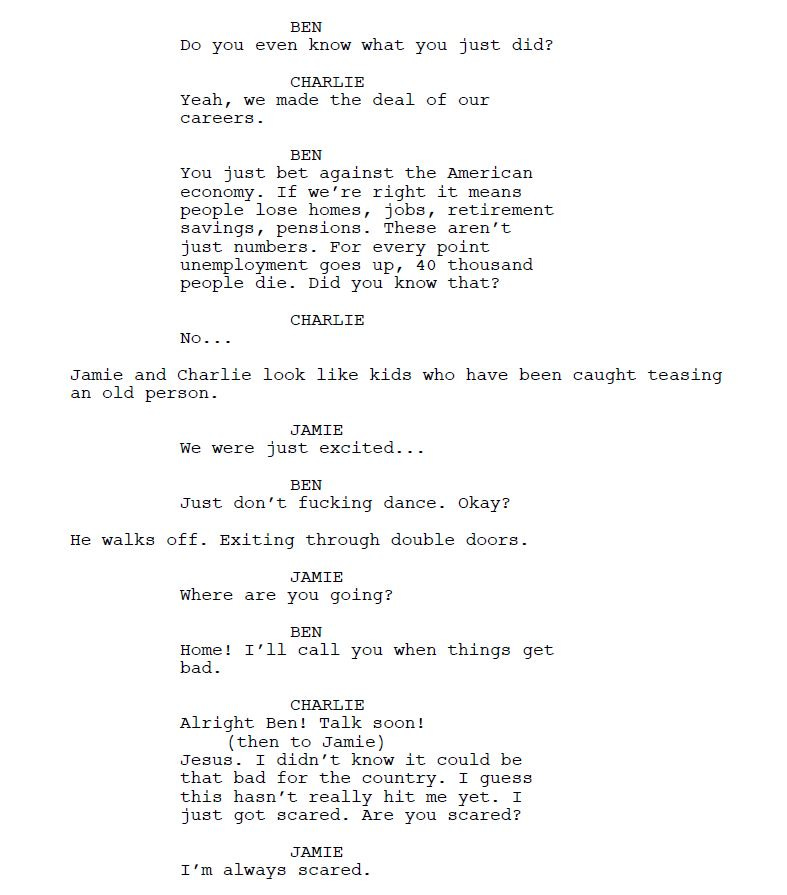

Nevertheless, the script is very much an ensemble affair, each offering different views of the collapse and how it affects them. Baum is torn because despite his tirades against Wall Street, he realizes that he is just as culpable as the system he blames. Charlie and Jamie are sobered by Rickert on page 85 when he spells out the cost of their victory:

Burry is the one with the least qualms, though also the one who takes the biggest hits in the time leading up to the crash, forcing him to lay off his employees and ultimately restrict his clients’ withdrawals from the fund that angers his biggest client, Lawrence Fields, simply because he could see what very few others saw.

The tale of Wall Street greed, and the system that rises and falls cyclically as a result of it, is a tale as old as Jeremiah (okay, maybe not that old, but at least two centuries old). Markets pick up, people get greedy and speculate, the bubble pops, markets fall, and eventually, it will pick up again. The only difference this time is that the blowup is larger than ever because the financiers and banks found devious ways of enriching themselves at the expense of the public, and ordinary people paid a heavy price for it. Writers Charles Randolph and Adam McKay did not want to skimp on the technical details because it is in the details that the powder keg hides, but how do you communicate this information in a way that is natural, easily understood, and doesn’t bring the pace to a screeching halt?

To understand how they tackled such an unwieldy subject, it is worth going back to the beginning. Randolph was the first writer to board the project, while McKay joined much later. Although neither of them collaborated on the idea-sharing process, they each aimed for the same goal, and that was to aim for a tone that was “slightly funnier than your average Milŏs Forman comedy” without leaning into full satire.

It was Randolph’s idea to make Mark Baum the center because Mark is the character who becomes what he procures. When Randolph began working on the script, he started with the characters in order to understand what defined and made them unique. To do that, he’d give each character a quirk (or what Blake Snyder would call a “limp and eye patch”), and then measured what he wrote against it. Randolph started by writing the Florida section first because that portion was not in the book; it was also around that time he realized the story’s potential comedy waiting to be unleashed. After three months of writing, and another three months of paring down the complexity, Randolph had a draft that was “more satirical” and had “more character-driven humor.”

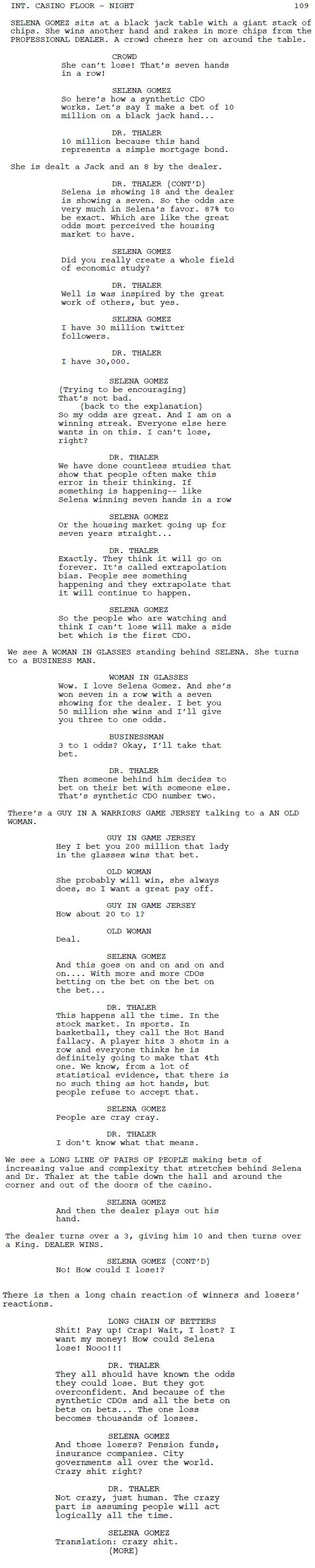

When McKay signed up to write and direct The Big Short, he brought his own strengths to the existing script— “more farce” to better communicate abstract and complex information. These included inserting celebrity cameos from the late Anthony Bourdain to Dr. Richard Thaler and Selena Gomez to break the fourth wall and parse the complicated jargon (Scarlett Johannsson’s cameo under a waterfall was swapped in the film for Margot Robbie in a bubble bath).

Meanwhile, it was Randolph’s idea to use Jenga blocks to visually describe the housing market’s shaky situation.

(Lucky the scene is interesting because if you thought about it too much, you’d suddenly wonder why Jared Vennett is explaining something that Baum’s FrontPoint Partners’ team already knows!)

Thanks to this, the addition of a narrator who occasionally breaks the fourth wall, and a comedic approach to the material, The Big Short manages to get people to understand difficult financial information and entertain them at the same time. It is an unusual way of telling a story, but by breaking the rules- and making it funny in the process- it works.

It also marked the beginning of McKay’s foray into socially-minded films, using his comedic sensibilities to make it easier to understand stories about difficult people and thorny subjects. But The Big Short might still be his best; it’s also the only one to net an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Of course, it’s worth noting that since McKay is known for allowing actors to improvise, the final film contains comedic bits that don’t appear in the screenplay. But that doesn’t mean the screenplay is any less funny. The improvisation works because the script has the main beats lined up and nailed down securely.

By bringing in their individual strengths, Randolph’s and McKay’s adaptation of The Big Short is a comedy, tragedy, drama, and farce, all at once. It is damning in its indictment of Wall Street, and absurd in the fact that it was allowed to ever happen this way. By using three stories as a triptych, it offers a snapshot into the heart of Wall Street’s greed, and paved the way for future scripts like Dumb Money to tell such stories. In some ways, it’s also a David vs. Goliath story, with the banks and traders on the Goliath side. Except the Davids in this situation aren’t that small—they just happened to be right.

Notes:

Hogan, Brianne (20 January, 2016) | Banking on The Big Short (Creative Screenwriting)