Slumdog Millionaire (2008) Script Review | #38 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Propulsive and electrifying, Slumdog Millionaire will keep you hooked with its romance of the star-crossed lovers at the heart of its rags-to-riches story.

Logline: After being accused of cheating on the Indian version of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” 18-year-old Jamal Malik reflects on his life growing up in the slums and surviving poverty alongside his older brother Salim, and Latika, the girl he falls in love with.

Written by: Simon Beaufoy

Based on: Q & A by Vikas Swarup

Pages: 121

Scenes: 197

Charles Dickens would be envious; with its rags-to-riches arc, social commentary, colorful characters, and star-crossed romance, Slumdog Millionaire is precisely the kind of story that the literary giant might have penned in his time. And the way it plays with multiple timelines without causing confusion would make Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino jealous.

All this, more or less, is to confirm that this is a fine screenplay.

How did Jamal Malik, a boy who grew up in the slums, correctly answer every question except the last on the Indian version of the game show, ‘Who Wants to Be A Millionaire?’

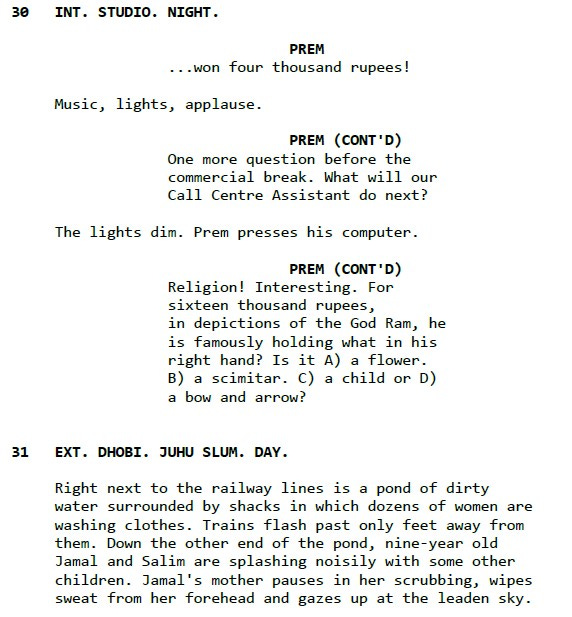

The game show host, Prem, thinks he’s cheating. The police Inspector and his deputy, Constable Srinivas, think so, too. Jamal, however, insists he knew the answers. How? Not from a textbook; but from his life.

Slumdog Millionaire has three timelines:

The Present Timeline (let’s call it ‘A’) – the main timeline, this focuses on the interrogation, in which Jamal is grilled and serves as a frame for providing backstory to how he knew the answer to each question exactly.

The Past Timeline (let’s call it ‘B’) – this timeline focuses on Jamal as a child, a teenager, and a young adult, and the various situations he wound up in that provided him the answer to the questions on the show.

The Immediate Past Timeline (let’s call it ‘C’) – this section is devoted to Jamal on the game show, and is sandwiched in between Timelines A and B.

The result is a tricky structure that could collapse underneath its own cleverness or simply result in baffling the reader. Especially since writer Simon Beaufoy wanted to avoid using captions such as “10 years earlier” to let us know at which point in time the story took place. With careful planning and painstaking arrangement, we understand exactly what’s happening when; where time is concerned, the screenplay never feels perplexing.

Another example of how it balances three timelines simultaneously and effectively:

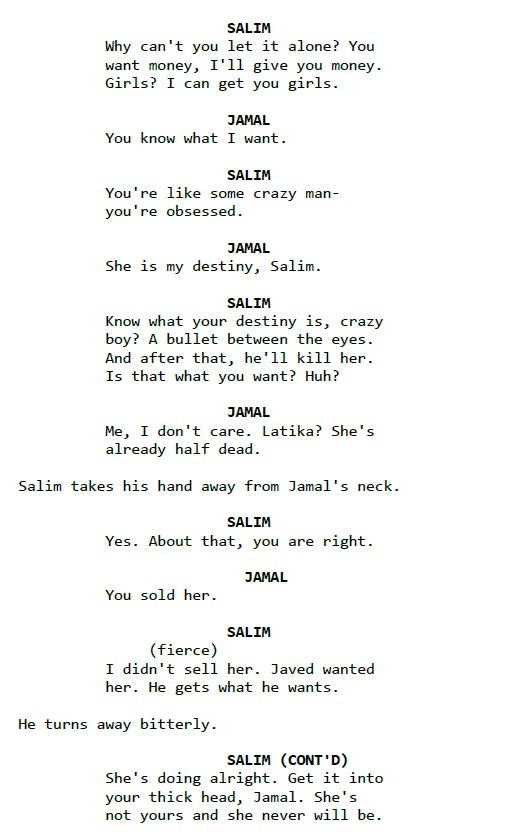

The A-plot is concerned with the mystery at hand: How did Jamal know the answers and will he win the show? The B-plot answers the reason why Jamal is on ‘Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?’ in the first place: it’s all about a girl. Latika. An orphan who joined Jamal and his elder brother, Salim, after the slums were attacked in a Hindu-Muslim riot and forced them on the streets. Now grown up, Latika is in the clutches of a vicious gangster, Javed; she stays because she has a roof over her head. Salim has also joined Javed to protect himself from enemies. Jamal, not unlike Oliver Twist, retains his ‘innocence’ and morality by not following his brother. He signs up for the show because he knows that Latika will be watching.

Not all timelines are created equal. Timeline B (the Past) takes up most of the time, as does Timeline C (the Immediate Past). But Timelines B and C conclude by page 105-106, the end of Act 2; Timeline A, the shortest in comparison, occupies all of Act 3. Having caught up with the events in Jamal’s life, it is time to see whether Jamal will correctly answer the final question and if he and Latika will be together after all.

The trick to managing such a complex non-linear story, therefore, is to use Acts 1 and 2 for the non-linear parts (or for events set in the past), and to keep Act 3 straightforward and linear (for concluding events in the present).

Compared to the final film, this draft dated November 4th 2007 contains a few subplots or scenes that were left on the cutting room floor. This includes a young Jamal learning about the meaning of an opera song from a Canadian woman that prompts him to return to Bombay and find Latika…

… as well as Scene 139 in which Salim scolds Jamal for going to see Latika…

… the kids getting caught spray-painting walls near a container yard, where Jamal steals a dress for Latika…

… and young adult Jamal’s living quarters back in the slum.

Another deleted scene includes the Inspector choosing not to charge Jamal with an unsolved murder, as well as a sub-plot about Prem and his love life. While they flesh out the world and add depth, it also takes attention away from Jamal’s story— which is complicated as it is. The script’s ending was also changed—it concluded with a musical number instead of a kiss. But preview audiences found that to be an emotional cheat, so the dance was moved to the credits, and a new ending added in which the two lovers kiss.

Slumdog Millionaire is a loose adaptation of Vikas Swarup’s novel ‘Q & A.’ The source material was both darker and different; Beaufoy recognized that the episodic structure and multiple storylines would not work in a film. He kept the chapters connected to the main narrative, jettisoned the rest, and merged the storylines into a single narrative. But Beaufoy’s troubles were only starting. For one, he had to crack the game show plot. “I just can’t get excited about money as a motivation in a film,” he said in an interview. Stumped, Beaufoy took the first of three research trips to India in order to get a feel for the country and community. What he found would soon prove instrumental.

As he interviewed and spoke to young street beggars and people living in the slums, Beaufoy was struck by their spirit to overcome their challenges. That was when he knew that he wanted to convey his impressions through the story, channeling “the sense of this huge amount of fun, laughter, chat, and sense of community in these slums.” Beaufoy also fell under the spell of the country; it was impossible to shake of the notion that the story had to be a love story. “India is brazenly romantic, utterly unashamed of its sentimentality,” said Beaufoy.

Armed with this insight, he decided to reinvent the story; the romance between Latika and Jamal would become the crux of the screenplay, not the quiz show.

Other influences steeped into the writing. Not just Mumbai, but the movies that Beaufoy imagined Salim and Javed would watch. As time went on, the British writer was perturbed to find that his attempts and nuance and subtext were being “replaced by something that [was] bordering on melodrama.” Rather than resisting, he let it work its magic.

“What use,” quipped Beaufoy, “is subtext in a city of such total extremes?”

But one hurdle still proved insurmountable: the structure. For weeks, it eluded him; the decision to avoid captions only stumped him further. It wasn’t until the fourth draft that Beaufoy finally found how to juggle it, though he’d continue tinkering and working on it after director Danny Boyle boarded the project.

For instance, despite its great use of visual transitions, the script’s opening alternated between Jamal at the show and Jamal being tortured. On page, it was meant to be funny; on screen, it was anything but. It seems that sometimes, what’s on the page may not translate exactly as intended when filmed.

The writing itself, meanwhile, is simple, but evocative. While he uses short lines to describe the action, he doesn’t hesitate to stretch it a little more when required, such as devoting six short but powerful paragraphs to capture the chaotic energy of the slums.

Since Beaufoy is a British writer telling a story about characters in a different country with different ethnicities, he recommends hanging out with people and listening to them speak— this was how he captured the voices of Jamal, Salim, and Latika.

Slumdog Millionaire rarely gets mentioned in the annals of pop culture and screenwriting, despite having won a slew of Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, and— pertaining to this piece— Best Adapted Screenplay. That’s a pity because its clever handling of non-linear narratives, its vibrant characters, its duality of darkness and light, makes for a compelling screenplay that has much to offer aspiring and established writers. Its inclusion on the Writers Guild’s List of Best Screenplays of the 21st Century is well-deserved.

Notes:

Roston, Tom (November 4, 2008) | ‘Slumdog Millionaire’ shoot was rags to riches (The Hollywood Reporter)

Script Magazine (June 28, 2019) | WRITERS ON WRITING: Simon Beaufoy on Writing Slumdog Millionaire (Script Magazine)

Sweet, Matthew (September 17, 2010) | Screenwriters’ Lecture: Simon Beaufoy (BAFTA)

Magnier, Mark (January 25, 2009) | Slumdog draws crowds, but not all like what they see (The Age)

The Hindu (January 11, 2009) | 'Slumdog Millionaire' has an Indian co-director (The Hindu)