Roma (2018) Script Review | #62 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Alfonso Cuarón draws from his personal life to create a moving and intimate story about the life of an honest and kind maid and the family she works for.

Logline: A year in the life of a middle-class family’s maid in Mexico City in the early 1970s.

Written by: Alfonso Cuarón

Pages: 135

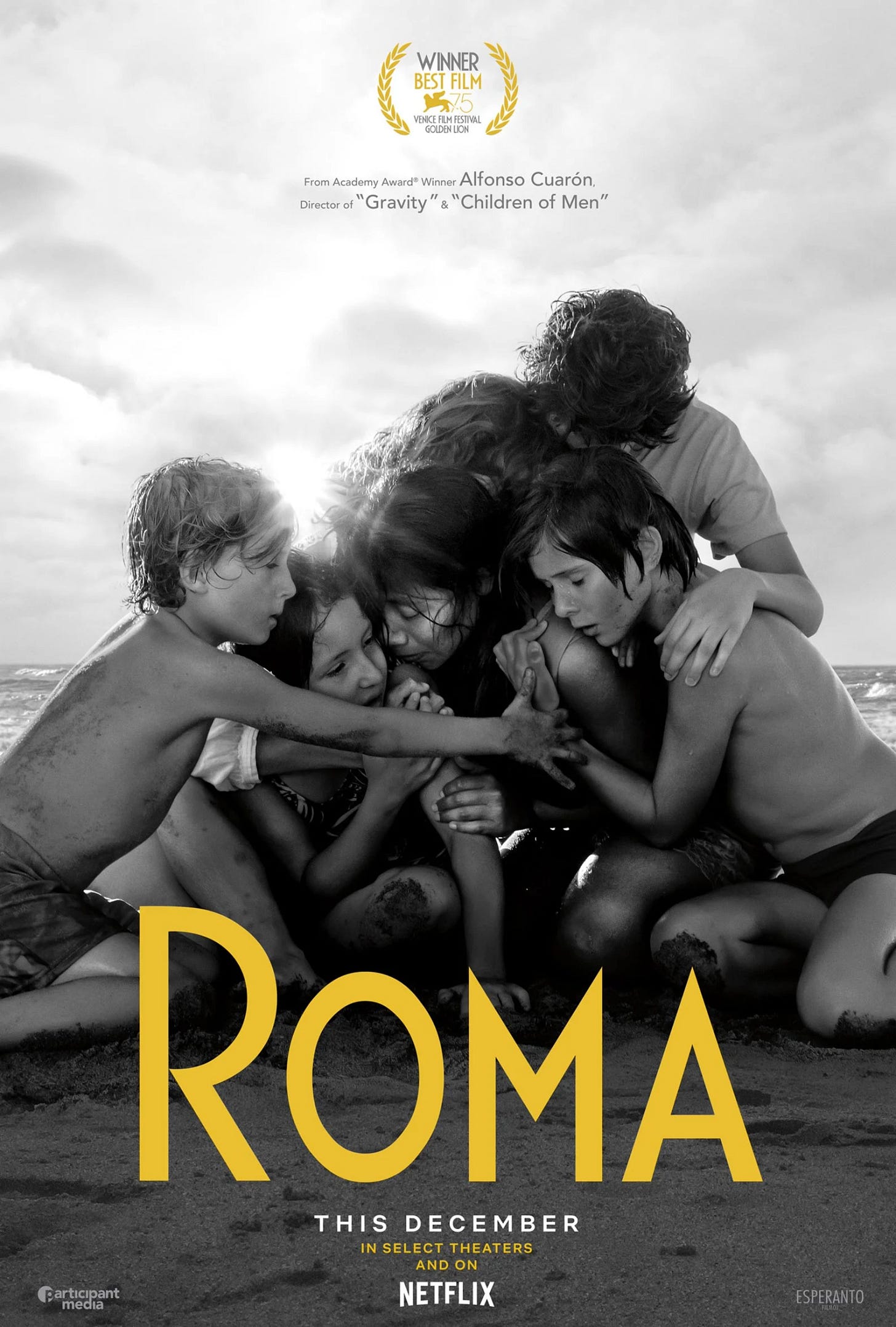

In the last few years, a new kind of story has emerged in cinema: Fictionalized or semi-autobiographical re-tellings of a filmmaker’s personal experience. (Jimmy Kimmel even joked that Hollywood has run out of original ideas that Steven Spielberg had to resort to his childhood for new material in the Fabelmans). Roma, however, stands out tall in this pack; perhaps due to its production (director Alfonso Cuarón served as his own cinematographer, shot it in black-and-white, made it for Netflix, filmed it with unknown actors and in Mexican, too, and walked away with a bunch of Oscars including his second statue for Best Director); but perhaps due to its intimate, un-fussy and moving story that is not about Cuarón at all, but that of his nanny, Liboria ‘Libo’ Rodriguez, during a particular year in her life set in the 1970s.

In the script, Libo becomes Cleo— a Mixtex indigenous woman in her late 20s who works for a middle-class family, the Roldáns, in the Colonia Roma neighborhood. Hence, where the script gets its title. The family comprises of patriarch Dr. Antonio (a doctor who is barely ever at home), his wife Sofía, their four children— Toño (12 years old), Paco (11 years old), Sofi (8 years old), and Pepe (5 years old)— and their grandmother, Señora Teresa. While the family treats Cleo kindly and as part of the family— and are there for her— it is impossible to erase the distinction that she is their maid, an outsider; something that is subtly reinforced whenever one of them asks Cleo to do something or make something.

[insert]

In Roma, two stories unfold: the A-plot is about Cleo, how she accidentally becomes pregnant by Fermín, a useless right-wing mercenary, and what happens to the baby; the B-plot is about Sofía’s marriage disintegrating, thanks to Dr. Antonio’s affair with a younger woman. Note, too, that in both instances, the script focuses on how two women must overcome the lack of dependability of the men they thought they could rely on. Meanwhile, Cuarón adds another layer to create depth: All of this takes place against a backdrop of political unrest in Mexico that led to the Corpus Christi massacre— which occurs around the same time that Cleo goes into labor. The result is a personal, social, and political story weaved together to show that life is personal, social, and political; to isolate them would be to destroy what makes these kinds of stories resonate.

While there is a structure and form underpinning the screenplay, it is not visible. Cuarón maps traditional plot beats (inciting incident, midpoint, low point) to the emotional arcs of Cleo and Sofía; as a result, he takes his time fleshing out the screenplay, not minding that plot developments don’t happen around the expected page numbers.

For instance, it’s almost around page 30 when Cleo meets Fermín which results in the inciting incident (the pregnancy); traditional screenplays are usually wrapping up Act I around this point. Nor do certain plot beats fit expectations— the Midpoint could be taken as the dawn of the New Year when everyone is frantically trying to put out a fire. While Midpoints are supposed to indicate a change in the story’s trajectory, this Midpoint is more symbolic, using fire to foreshadow chaos that threatens to burn and destroy everything. In this sense, Roma owes more to the works of Ingmar Bergman and other European filmmakers than Hollywood, right down to creating a poetic story that brims with profundity and melody.

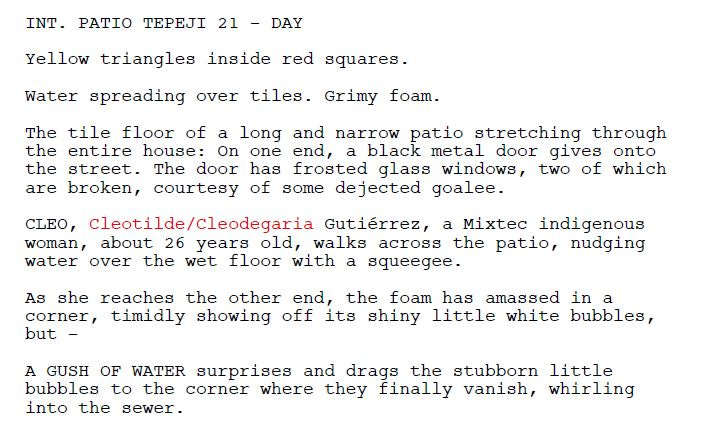

Cuarón loves his symbolism and imagery. Consider the opening image of the screenplay:

Water becomes a symbol for the force of life, more explicitly shown in the screenplay’s climax when Cleo overcomes her fear of the sea to wade in and rescue Paco and Sofi. Consider, too, the final scene: Cleo climbs a metal stairwell to the roof in such a way to imply that she has ascended, almost into a state of grace.

Cuarón also inserts a lot of foreshadowing over the baby’s fate— three times, in fact. The first is when Cleo is in the hospital and visits the Maternity Ward… and this happens:

The second instance occurs on page 70:

And the third is when Cleo goes into labor at the same time that students are being massacred by right-wing paramilitary forces to which Fermín belongs to (in fact, it’s implied that Cleo encountering him sent her into labor).

Imagery and symbolism are powerful techniques used not only in cinema but in prose, theater, and poetry. But often, many filmmakers either don’t use it or forget to use it— there is an anxiety that the reader/audience might not get the message, so they resort to spelling everything out (American cinema is especially guilty of this). I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it’s largely non-American writers and directors like Cuarón who pay more attention to imagery and symbolism, and that’s a shame because film is a visual medium, and imagery works wonders when done rightly.

The script is an English translation, presumably prepared for the English-speaking financial backers, but it still contains snippets of Mexican dialogue that creates authenticity in building out the world of Roma. Now some writers forgo extraneous details, preferring to leave it up to the other departments to figure out or to avoid taking up too much space on the page; not Cuarón! He goes into detailed description, and the effect is that as the reader, you feel transported into this 1970s neighborhood. The writing is more literary than you’d expect from a screenplay, and it is beautiful. Of course, Cuarón can get away with it given that he’s built a rock-solid reputation by the time he wrote Roma, but I think even emerging writers could take a cue from him— don’t hesitate to make your screenplay feel personal, no matter what the rules say, so long as it helps to draw your reader in.

Another example:

Moreover, Roma doesn’t shy away from the less appealing parts of the culture— and, once again, it is caused by the men. The casual low-key sexism, misogyny and machismo that pervades the times (unfortunately, I can relate because my culture suffers the exact same problem). This is noticeable predominately when the family goes to the villa to spend New Year’s Eve with friends. The husbands take to showing off their shooting skills outdoors; one slaps the ass of a 17-year-old servant…

… and tries to seduce Sofía, but when rebuffed, cruelly insults her appearance…

… and another, most insidiously, inappropriately hugs a 12-year-old girl by showing her how to shoot a gun.

Maybe Cuarón did this deliberately, maybe it was serendipitous, but Roma really is a script about the women in his family who kept them together and brought them up. It’s a feminist screenplay in that it portrays the complicated lives of two women without exaggerating them in the way that Hollywood tends to do (and thereby trigger the incels waiting to howl at the drop of a hat).

Apart from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Alfonso Cuarón has written—either solo or with others— the scripts for his movies. In doing so, he has greater control in shaping the narrative to his sensibilities. He’s a visually oriented director, and this is conveyed in his writing that finds a way to accomplish this without resorting to writing camera directions. The result is a screenplay that is engrossing to read.

If you want to write a screenplay based on your personal experiences (or those of someone you know), Roma offers a template for how to accomplish this:

Fictionalize your characters (obviously).

Ensure that there is a structure instead of a series of disjointed anecdotes that leads nowhere.

Don’t be afraid to show the political times during which this story is happening IF you can find a way to connect it thematically or through imagery.

Be honest and true to your characters.

The world can be a cruel and ugly place filled with cruel and ugly people. As writers and storytellers, it’s our job to find the beauty that exists but is often hidden among the muck and despair. Roma is proof of what happens when you excavate and show the world about the wonderful things they didn’t know were there.