Ocean's Eleven (2001) Script Review | #75 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Ted Griffin assembles a delightful and clever caper in a remake superior to the original Brat Pack movie.

Logline: Less than 24 hours into his parole, charismatic thief Danny Ocean is already rolling out his next plan: In one night, Danny's hand-picked crew of specialists will attempt to steal more than $150 million from three Las Vegas casinos. But to score the cash, Danny risks his chances of reconciling with ex-wife, Tess.

Written by: Ted Griffin

Based on: A screenplay by Harry Brown and Charles Lederer, and a story by George Clayton Johnson & Jack Golden Russell

Pages: 148

Number of scenes: 297

Ocean’s Eleven is the rare remake that improves on its predecessor and works better than the original. Despite its 148-page count— mainly due to some scenes having extra pages tacked to them— Ted Griffin’s screenplay moves as confidently and astutely as its protagonist; never a step out of place, and stuffed to the gills with charm and wit. It is a great example of how to write a heist movie with memorable characters, as well as how to write an ensemble screenplay— because Ocean’s Eleven succeeds at both.

For all its layers of deception and red herrings, the plot is quite straightforward. Danny Ocean, straight out of prison, is already planning an ambitious heist: Steal $150 million from three Las Vegas casinos in one night. The target: Terry Benedict, a ruthless casino mogul. Ocean assembles a team of specialists to carry out the job, a mix of old friends and new faces, but when it turns out that Benedict happens to be dating Ocean’s ex-wife, Tess, one begins to wonder whether Ocean making it personal will get the crew caught or killed.

If there is a good formula for drama, it would be this: Intention and Obstacle. Your protagonist wants something; but something stands in their way of getting it. To add depth, give your protagonist both external and internal intention (or wants). This is how it plays out for Danny Ocean:

External Intention (Want): To steal $150 million from three Las Vegas casinos belonging to a mogul in one night;

Internal Intention (Want): To win back his ex-wife who happens to be in a relationship with said-mogul.

Now each Intention (Want) comes with its own Obstacle:

External Obstacle: The vaults are near-impossible to break into, and if the mogul catches them, he will destroy their lives;

Internal Obstacle: Ocean’s ex-wife does not want to be married to a thief.

Having the stakes clearly outlined prevents confusion and helps to keep things focused, especially with such a large number of characters. Which brings us to another problem: How do you write an ensemble screenplay without it being overstuffed and underbaked?

First, here’s a list of Ocean’s crew and their skills:

Danny Ocean – the mastermind

Rusty Ryan – the point man

Linus Caldwell – the pickpocket

Livingston Dell – the electronics expert

Frank Catton – a con man who goes into the casino to gather intel

Saul Bloom – a con man who befriends the mark (Benedict)

Basher Tarr – the ammunitions expert

Reuben Tishkoff – the heist’s funder (who also has personal beef with Benedict)

Virgil Malloy – gifted mechanic and driver

Turk Malloy – gifted mechanic and driver

Yen – an acrobat and grease man

The secret, as per Ocean’s Eleven, is that only a few characters will be given an arc and experience growth, while the rest remain static, though they each get at least one moment to show off their talent. In Ocean’s Eleven, you might be surprised to learn which character(s) receive the spotlight to grow and evolve.

It is… drum roll, please… wait, Linus Caldwell?

What? But Ocean is the main character, you argue. Shouldn’t he be the one to experience character growth?

You’d be correct— except Ocean doesn’t change. At all. By the end of the screenplay, he’s the same person he was at the start, only this time he’s richer and he has won the girl. In contrast, Linus— the son of a famous pickpocket—is the greenest member of the crew who has the most to prove himself. This occurs when Linus (briefly) replaces Ocean to get the vault codes from Benedict and is the one entrusted to help Ocean break into the vaults, helping him to distinguish himself.

There’s another reason why Ocean doesn’t undergo change— he’s too charismatic and clever to change believably. All he has to do is prove that he cares more about Tess than he ever will— and maybe not commit any more heists after this job. As for Rusty, he gets his own arc in the sequel, Ocean’s 12, while the third installment, Ocean’s 13, doesn’t have any arcs as such (but that’s a post for another time).

Lesson for the aspiring screenwriter: In an ensemble screenplay, only ONE character should undergo change, and it does NOT have to be the main character; however, the main character SHOULD achieve what he/she wants by the end.

Another question when it comes to ensembles: How many pages should you devote to assembling the team? Griffin spends about 10-15 pages setting up the various characters which serves as the end of Act I, while Act II brings them altogether around page 35. This is how it plays out:

First, we meet Ocean.

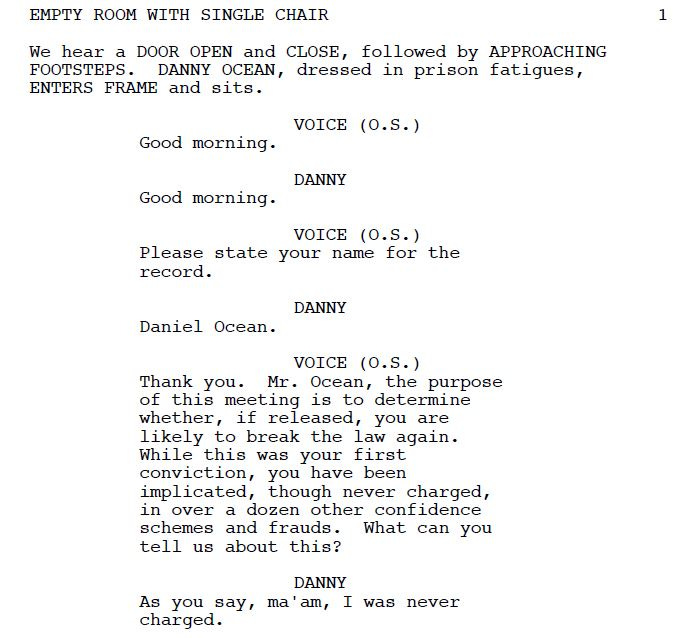

Then, Ocean meets Frank on page 4.

Next, Ocean meets Rusty on page 12.

On page 21, the recruitment really begins.

As for the heist details, those are saved for Act II, and this is an observation I made while reading that I thought is worth noting: Act II is largely uneventful. The rising action proceeds more or less smoothly from page 35 in a series of amusing scenes as Ocean’s team being reconnaissance, allowing each team member to demonstrate why they were hired for the job.

It’s only at the Midpoint on page 58 that they learn about Tess, which disrupts their plans and raises a question: Will Ocean compromise the heist if it means getting a chance to reconcile with Tess?

From this point on, they experience some setbacks— and the end of Act II (the low point) ends with Linus being substituted in Ocean’s place; although in a twist, it turns out that this “low point” was a feint— Ocean wanted to give Linus a chance to show what he could do!

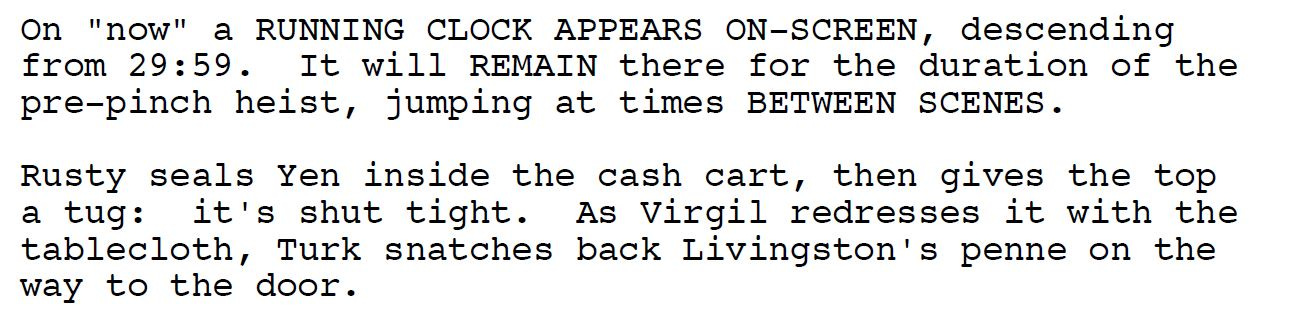

In Act III, Griffin adds a countdown that does not end up on the screen but serves three useful purposes:

a) it orients the reader as to which points in the plot certain events should happen;

b) it builds tension as the timer counts down to zero;

c) it substitutes as the time of day in sluglines.

Griffin’s writing is economical, precise, but never rote. He does incorporate camera directions but never obtrusively, and he uses asides and comments to engage the reader, a tactic that writers like Shane Black use…

There’s no set way on how to write a screenplay, except write it in a way that grabs the reader by their collar and never lets them go until the final page.

In many ways, Ocean’s Eleven is like The Godfather in that we sympathize with Ocean and his crew, and even root for them because the antagonist, Benedict, is worse than them. If you take a step back though, you realize that Benedict is actually the victim and Ocean and his crew are criminals. If you want to build empathy for characters with less-than-moral motives, you need to create an opponent who makes them look good so that you want the antagonist to fail, even if they haven’t even done anything to the protagonists.

The screenplay doesn’t exactly line up with the finished film— largely because director Steven Soderbergh would take advantage to mix things up in the editing room. But the reason the film succeeds is because the story first succeeded on the page. Ted Griffin’s screenplay is air-tight, the heist is a doozy (as long as you don’t question it too much), and every page oozes with fun. Like its eponymous character, the script is assured and clever, dazzling you with its brilliance. If you want to write a heist screenplay, or an ensemble screenplay, use Ocean’s Eleven as your blueprint— for it pulls it off in every way possible.