Memento (2000) Script Review | #10 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A riveting neo-noir that set Christopher Nolan on the path to critical and commercial success, the seeds of his style and trademarks planted here in retrospect.

Logline: Suffering short-term memory loss after a head injury, Leonard Shelby embarks on a grim quest to find the man who raped and killed his wife. But although he can recall details of his life before the accident, he cannot remember what happened fifteen minutes ago, raising questions about his life and his pursuit of justice.

Written by: Christopher Nolan

Based on: The short story “Memento Mori” by Jonathan Nolan

Pages: 119

Scenes: 183

When you look past the cleverness of its non-linear approach, Memento turns out to be a straightforward modern-day noir. I don’t mean that as a criticism or even a backhanded compliment, I’m only making an observation. It is the very simplicity of the narrative that allows Christopher Nolan to take a creative risk in how he lays out the sequence of events in two parallel tracks. One told in reverse, the other moving forward, until both converge.

A man named Leonard Shelby is on a quest. He’s searching for his wife’s assailant and murderer, a man only known as ‘John G.’ There’s a slight hitch: on the night she was killed, Leonard suffered a head injury that prevents him from forming new memories. That means he can’t remember anything beyond 15 minutes. To cope with this short-term memory loss, Leonard tattoos facts all over his body and keeps a stack of Polaroids with details written on their labels. He’s aided on his mission by two people: a bartender named Natalie, and another named Teddy. But neither of them appears to be trustworthy or reliable; in fact, as the script progresses, Leonard doesn’t appear to be so reliable, either. Is it possible that Leonard had already dispensed vigilante justice on his wife’s killer? Is it possible that Teddy, an undercover officer, is using Leonard for his own ends? Is it possible that Natalie’s sympathy is false because Leonard killed her boyfriend thanks to Teddy? In fact, is it possible that Leonard’s wife actually survived the assault, and then actually died because Leonard gave her a fatal overdose of insulin because he could never remember when he administered the medicine?

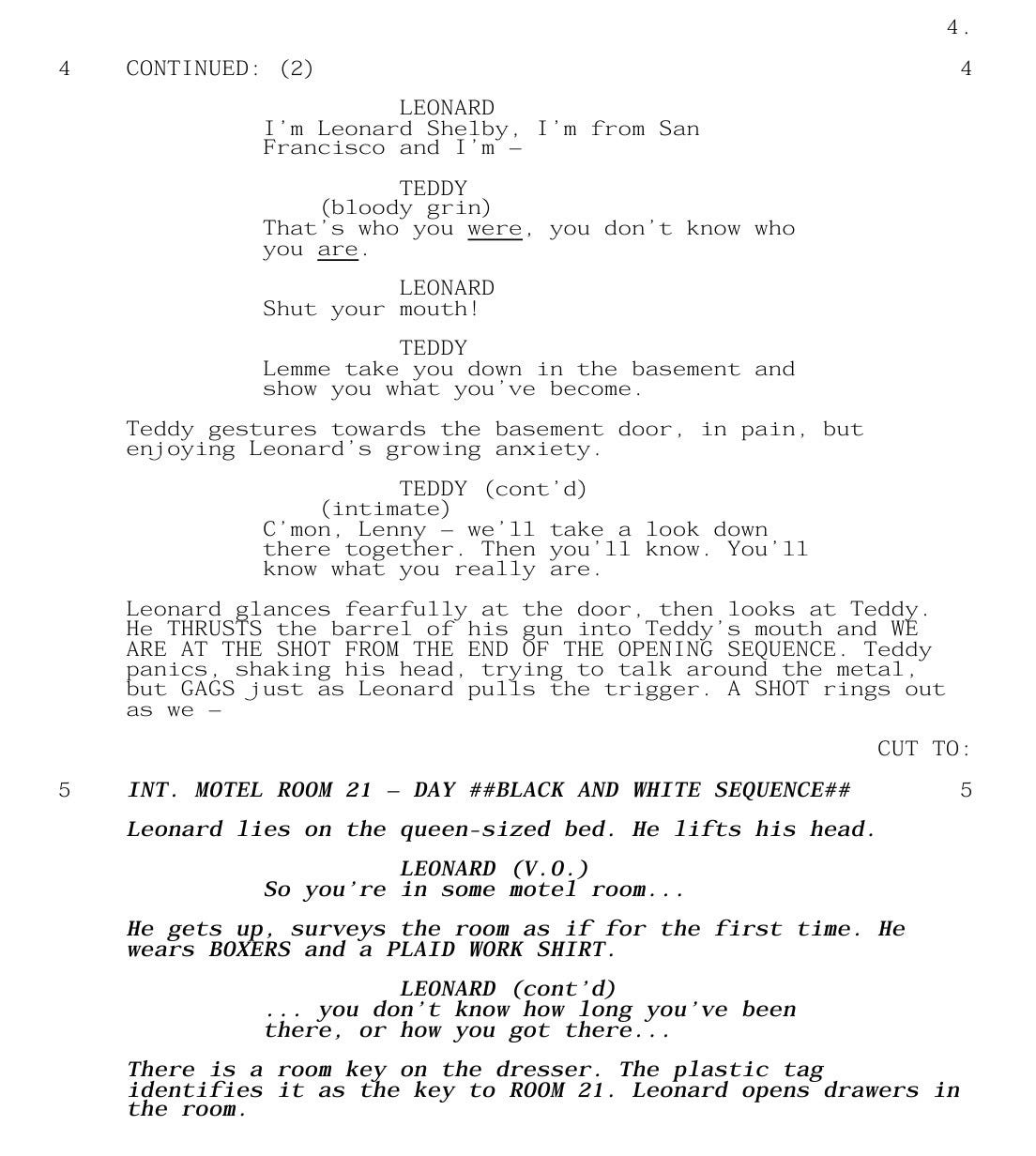

The first sequence of events told in reverse is shown in color; the second in black-and-white. It opens with a bravado scene that plays in reverse, starting with the corpse of a dead man with his head blown off that reassembles into the face of a man right before he was shot in the mouth. Note, too, that at no point does Nolan indicate that this scene is playing in reverse.

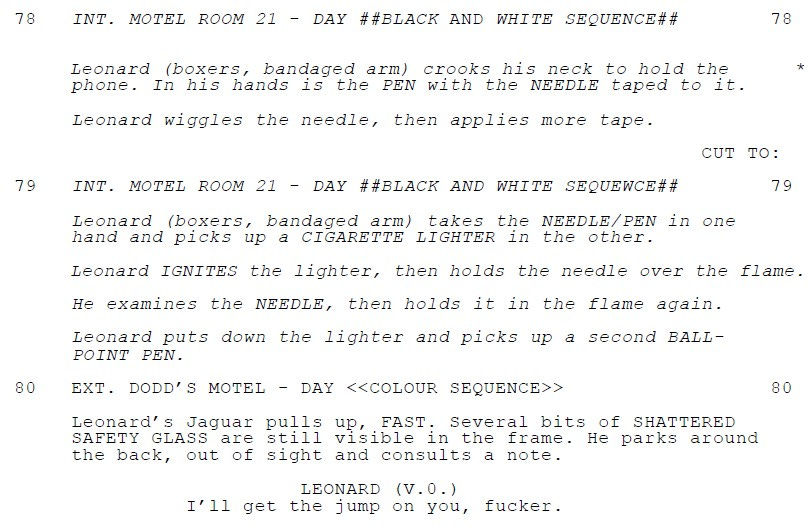

To distinguish the color sequences from those in black-and-white, this is how Nolan formatted and indicated it to make it easy:

The plot is cyclical, almost Lynchian in its tone. Nolan wanted to make a film noir “but with a subversive modern or postmodern spin.” Since it would have to be made on a low-budget, the plot was kept to a minimal— most of Memento is restricted to settings in and around motels; a derelict house, a restaurant, a diner, a house, a parking lot, an office, and a bar. The cast is kept small— apart from the aforementioned principals, others include a guy named Burt, another named Dodd, and an unnamed prostitute; in flashbacks, we see Leonard’s wife, as well as a couple whom Leonard claims to have investigated when he worked in insurance, Sammy and Mrs. Jankis. Sammy suffers the same condition that Leonard does; the twist is that Sammy’s story is really Leonard’s story, supressed and reconfigured so that Leonard doesn’t have to feel guilt.

Despite the non-linearity of the Memento screenplay, Nolan claims it was “the most linear script” he has ever written. The idea to tell it backwards occurred to him two months into working on the first draft, crystalizing everything required to tell it. He wrote much of it in motel rooms along the California coast (it was around the same time, circa 1997-1998, that he was hustling to get his first feature film, Following, into film festivals). An unlikely influence was Radiohead’s seminal album, ‘OK Computer,’ which he listened to while writing; despite listening to it so many times, Nolan finds that he can never remember which song comes next. Having worked out the story for a long time in his head, he wrote it straight through so that he could experience events happening just as Leonard did.

To prevent confusion when reading, Nolan indicates early on as to where we are in the story, though he only does it once. From there on, it becomes easy enough to follow the story as it progresses.

There’s humor…

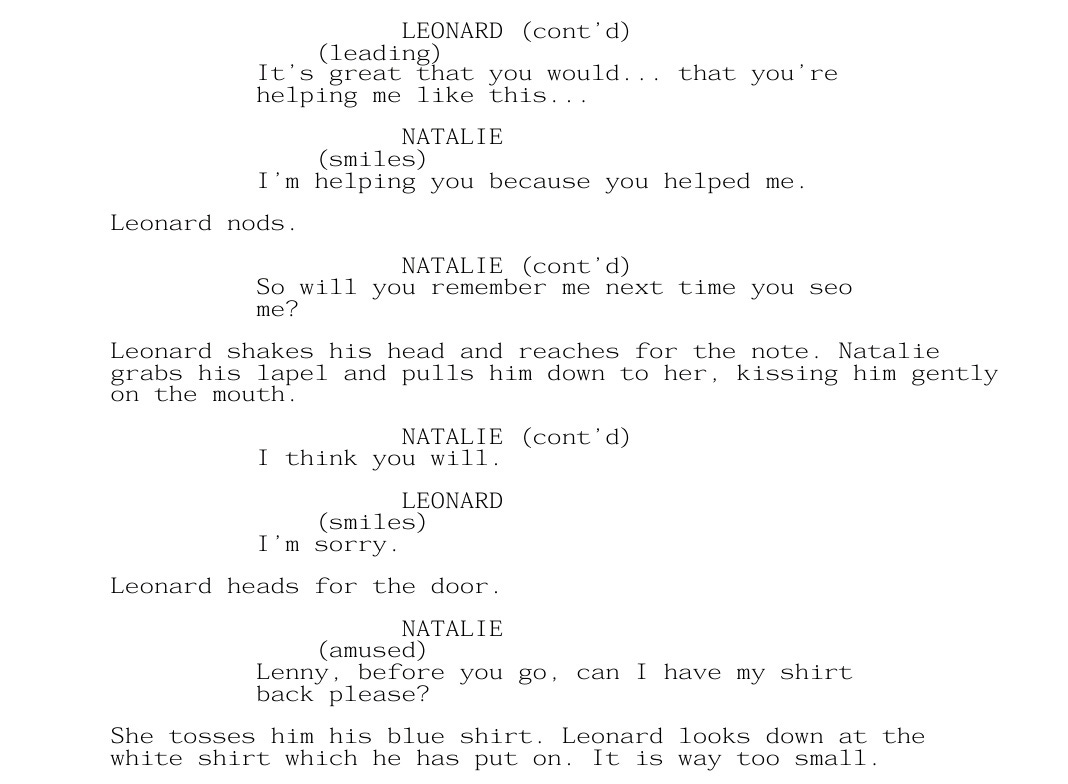

… and parentheses…

And judging by the formatting, it appears to have been typed out on a word processor like Microsoft Word.

Although Memento would become his second (and breakout) feature, it would be Nolan’s first adaptation. It was based on a short story written by his brother, Jonathan Nolan; the younger Nolan sibling had learnt about anterograde amnesia in a psychology class he’d been taking, and was haunted by a harrowing experience of getting held up and robbed while holidaying in Madrid. Obsessing over this incident for three months and what he could have done instead, an image popped into his head: a guy in a motel room, his body covered in tattoos, having no idea how he had ended up there. On a road trip, Jonathan Nolan shared the idea with his brother. Christopher Nolan was intrigued, and asked if he could adapt it.

The short story, ‘Memento Mori’, (which is included in the screenplay) is different to what the elder Nolan would end up writing. Not just in characters but in situation, too. For the screenplay, Nolan was particularly interested in exploring how Leonard’s condition would make it easy for people to use him. This is demonstrated vividly in Scene 139— no words needed to explain how cruel it is.

Or in Scene 123, when Natalie displays her true colors.

The first draft of the Memento screenplay ran 170 pages. Two drafts later, Nolan had whittled it down to a 150-page version that he felt confident enough to show people to get feedback— his brother, Jonathan, his producer (and later, wife) Emma Thomas, executive producer Aaron Ryderf— but he’d continue tinkering with the script and ironing out problems until it was 127 pages, and good enough to shop around.

“I always remember Emma reading the script of Memento for the first time,” Nolan says in Tom Sloane’s book, The Nolan Variations. “Every now and again she would stop reading, turn back a few pages to check something with a frustrated sigh, and then start reading again. She did that many, many times before she got to the end. She had a very clear-eyed view of how it worked, what worked about it, what didn’t. She’s very, very clear on what the audience are capable of taking in and when you’re just spinning your wheels. She’s always been extremely helpful to me in terms of pointing out areas where I’m sacrificing clarity.”

What changed between the first draft and the shooting draft? In part, it included a lot of simplification. In the first draft, Leonard stayed in two motels; this was to highlight the cyclical nature of the story. But two motels turned into two rooms at the same motel. Likewise, the motel clerk character, Burt, merged from two men into one. Another change was made to the black-and-white sequence; originally one long scene, it would be scattered throughout the story in bits and pieces to build dread and act as a buffer between the other scenes). Although Nolan finished the script in the spring of 1998, he was still trying to figure out the ending. Jonathan, who’d arrived in Los Angeles by then, provided the twist that would be the story’s eureka moment: the fact that Leonard had already done what he had been trying to do all this time.

Beneath the wizardry is an uncomplicated story. A man deceives himself into thinking his wife’s killer is still out there, and is used by an undercover cop and a ruthless woman. Nolan loves to tell familiar stories in new ways. Memento also poses some intriguing notions about how our memories work and how valuable they are in helping us to navigate through the world. Some might say the non-linearity is a gimmick, but it’s well-handled here and showcases Nolan’s talent extremely early on, earning him his first Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. In hindsight, it also contains seeds and ideas that would crop up in later films— the use of two timelines, one in color and the other in black-and-white, was used in Oppenheimer; the opening scene where everything plays backwards would form the entire basis of Tenet; the multiple timelines also popped up in The Prestige (#82 on the WGA List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century) and the converging timelines would play more ambitiously in Dunkirk. In many ways, Memento feels like a blueprint for much of Nolan’s future filmography. It ambitiously overcomes its limitations to tell a tight and effective story that still has the power to intrigue and enthrall.

Notes:

Shone, Tom (2020) – The Nolan Variations: The Movies, Mysteries, and Marvels of Christopher Nolan

Neff, Renfreu; Argent, Daniel (July 10, 2015) | Remembering Where it All Began: Christopher Nolan on Memento (Creative Screenwriting)