Mean Girls (2004) Script Review | #34 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Endlessly quotable and sharp, Tina Fey's first (and still, only) feature film screenplay endures two decades later.

Logline: When Cady Heron moves to a new school, she becomes an instant hit with the Plastics, the A-list girl clique, until she makes the mistake of falling for Aaron Samuels, the ex-boyfriend of alpha Plastic Regina George.

Written by: Tina Fey

Based on: Queen Bees and Wannabes by Rosalind Wiseman

Pages: 117

This draft is a little darker than the version that was filmed and ends differently, yet the bones of what would become a classic are very much in place. It’s intelligent, it’s amusing, and it’s instantly quotable. Three qualities that all screenwriters secretly hope their scripts contain.

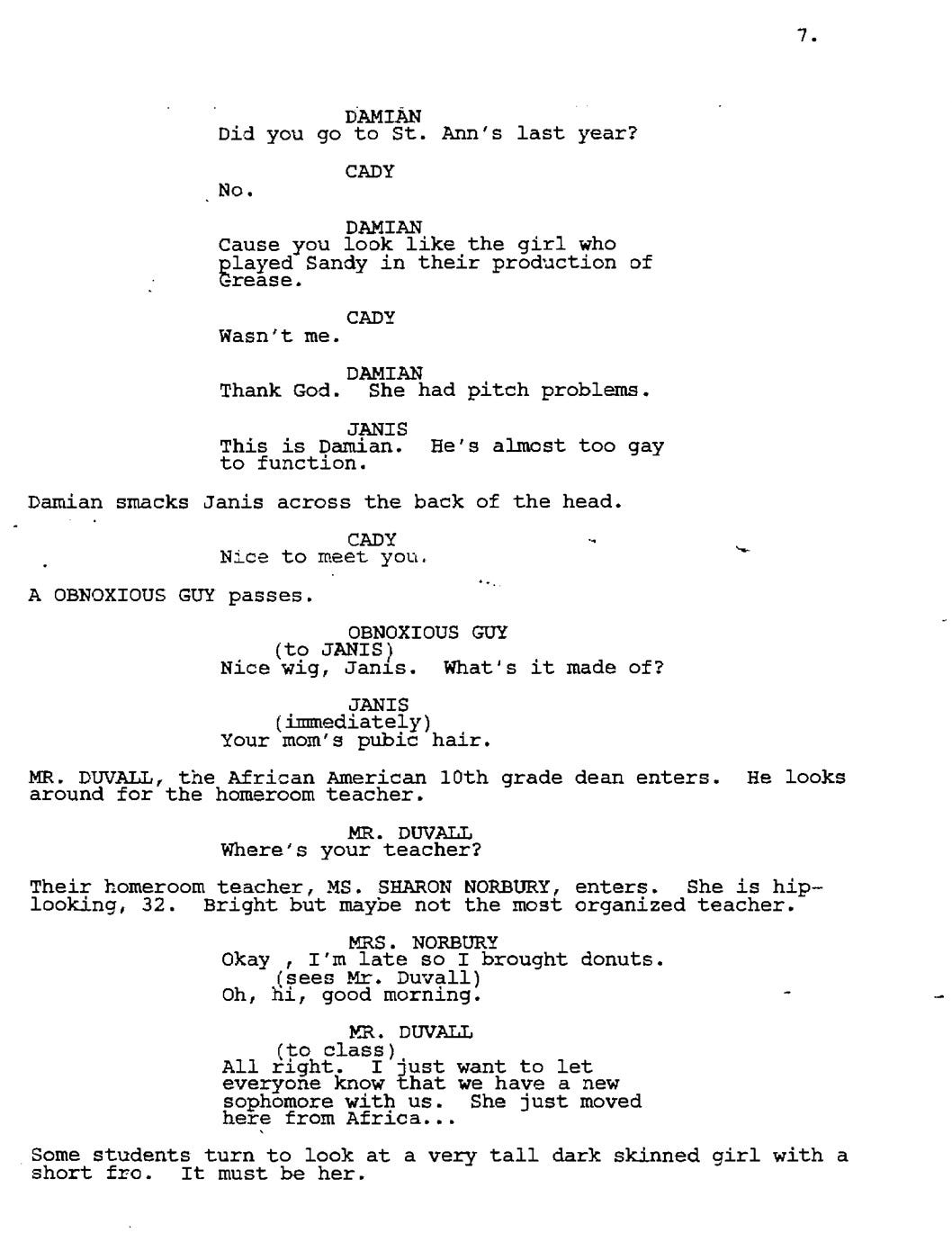

Mean Girls follows the exploits of Cady Heron, a homeschooled teenager who attends a high school for the first time— at the age of 15. Her parents are research zoologists and spent most of her life in other countries, the last being Namibia (it reminds me a great deal of Nickelodeon’s The Wild Thornberries TV series). On her very first day, she gets drafted into the school’s A-list girl clique, the Plastics, and discovers that high school in Evanston, Illinois can be as deadly as the savannahs in Africa.

A bulk of the comedy arises from Cady being in a fish-out-of-water situation. Despite her smarts, especially in math, she’s clueless about high school. She gets help from two outcasts, Janis and Damian; Janis is a goth-like rebel artist, and Damian is “almost too gay to function” (their words, not mine!).

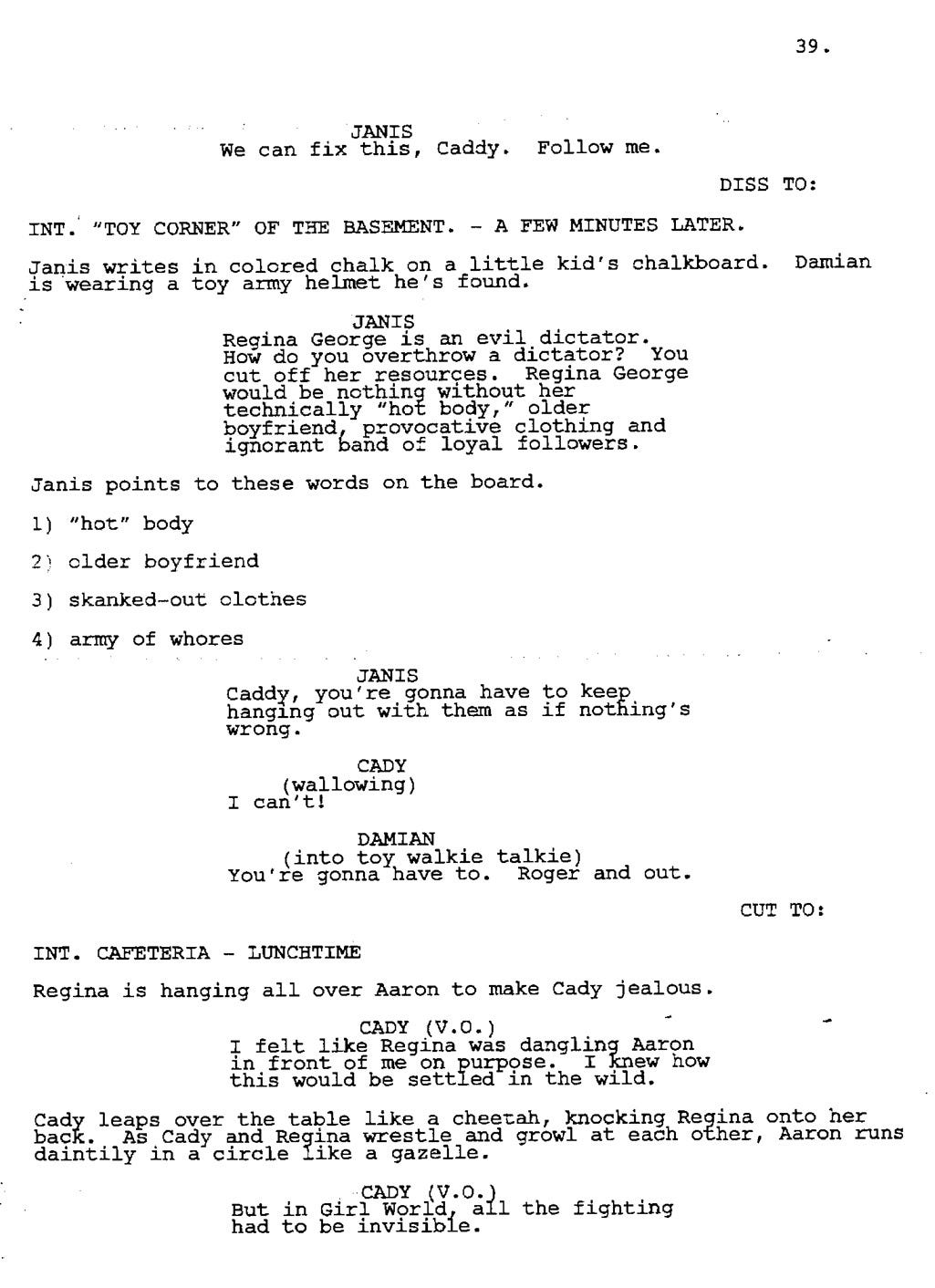

When chance opens an opportunity for Cady to befriend the Plastics—Regina George, Gretchen, and Karen— Janis pushes her to accept. She wants to get revenge on Regina for ditching their friendship years ago.

But something happens that Cady was not unprepared for: In pretending to be a Plastic, her personality begins to transform. Subtly at first, then more noticeably, at the expense of sacrificing her interests and good qualities; until, at last, she has turned into a version of Regina.

One of the admirable qualities of Mean Girls is the way it takes pains to chart Cady’s transformation and eventual fallout. It documents all the small and big ways that people— in this case, women—can help or hurt their adolescent peers, proving the old adage that high school truly is hell. But it refrains from turning them into stereotypes; instead, it gives us flawed characters.

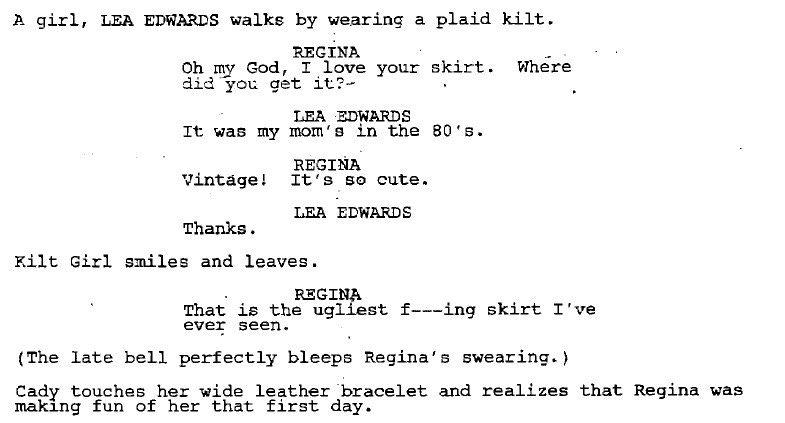

Take the antagonist, Regina, for instance. She is not written as outright evil, but she’s good at studying people and knowing the levers to press. The scene where she compliments something ugly shows that she is an astute observer; she’d make a great CEO.

When Cady expresses an interest in Aaron Samuels, who happens to be Regina’s ex-boyfriend, the Plastics leader sabotages her by promising to help set her up only to rekindle the romance with Aaron herself. It’s not even that she’s interested in Aaron; she merely doesn’t want Cady to have him.

A good portion of Act 2, then, is devoted to the plan on taking down Regina. Cleverly cooked up by Janis, the plan involves covertly fattening up Regina with weight-gain protein bars, exposing her as unfaithful to Aaron, and straining the ties with the other Plastics, Gretchen and Karen. Although they succeed, Regina retaliates by plunging the school into anarchy and putting all the blame at Cady’s feet. She accomplishes this by revealing the existence of a ‘burnbook’; it’s a book maintained by the Plastics in which they write anonymous (and mean!) things about the people in their school. Today, it would just be a Facebook or WhatsApp group. And when I say anarchy, it’s not hyperbole.

Amid all this, there is a sub-plot about how Cady’s actions directly impact one teacher, Ms Sharon Norbury, when she accidentally witnesses the teacher confiscates drugs from a student and unintentionally makes it seem like Ms Norbury does drugs. In fact, this sub-plot gets omitted in the final film as in this script draft, the climax becomes a school board meeting in which Cady helps to get Ms Norbury reinstated; in the film, it’s changed to the Mathletes contest.

Another difference is that fan-favorite character, Kevin G., doesn’t get a lot of attention in this draft as he would in the film. There’s also more swearing.

Tina Fey was inspired to write Mean Girls after reading Rosalind Wiseman’s non-fiction self-help book, ‘Queen Bees and Wannabees.’ However, the screenplay is a completely fictional story; rather, it uses the book’s lessons and observations about girls in high school to form the base of the narrative. Such lessons include the importance of small moments such as not being invited to a party. For the story, Fey drew from her own life and experiences, right down to the characters. For instance, Cady Heron was inspired by her friend, Cady Garey. And Regina’s habit of complimenting people as a way of making fun of them? That was based on a habit of Tina Fey’s mother! Perhaps the most amusing revelation is that Fey used to be a mean girl back in the day; perhaps that’s why she is able to find the humanity in the Plastics, even if they seem vapid.

It was in 2002 that Fey pitched the idea of Mean Girls (originally titled Homeschooled) to Lorne Michaels, the Saturday Night Live producer. Having read Wiseman’s book, Fey described it as “a movie about what the call ‘relational aggression’ among girls.” Michaels, though probably bemused, agreed to back her up and step in as a producer. That’s how during the summers of 2002 and 2003, Fey would work in a “mild dewy” backroom in a Fire Island rental home, hunched over a desk and fueled by Entermann’s chocolate-covered donuts and coffee, cranking out the pages. Initially, Fey thought to set it from the point-of-view of a teacher (Ms. Norbury, presumably, whom she played in the film); but it wasn’t long until she realized that having the teenage girls as the main characters made it more interesting. Her background in comedy meant that the script found ways to skirt tropes or clichés, and extract the funny parts. In university, Fey was seen taking copious notes on her observations about the world to use as material; but although she had anecdotes and notes, she lacked a story. This shortcoming prompted her to devour books on screenwriting such as ‘Save the Cat’ as well as the ideas of screenwriting guru Syd Field (she even got index cards).

That, combined with writing what she knew, turned Mean Girls into the gift that keeps on giving. It boosted everyone’s careers and paved the way for Fey to create the hit series 30 Rock; amazingly, she would never write another feature, at least to date. Not that she needs to—the strength and endurability of Mean Girls has allowed her to build an entire mini-empire off this one story, including a Broadway musical that led to a film adaptation of the musical in 2024. She continues to tinker with it 20 years later, namely by updating the humor, as she realized that some of the jokes that worked in the early 2000s would not pass muster today.

Yet it’s not the comedy that makes Mean Girls memorable, even if it is golden. It’s the characters; it’s the astute observations (particularly a humorous one set in the mall) and the narrative that makes the script compelling.

Even if it isn’t the final draft, most of the ingredients are here. For a screenplay titled Mean Girls, it’s got plenty of heart. Fey has penned a classic that, decades later, still resonates and is endlessly quotable.

Notes:

Spencer, Ashley (January 10, 2024) | Tina Fey on ‘Mean Girls’ Then and Now (The New York Times)

Digital Editor Team (September 12, 2021) | ‘Mean Girls’: The Book That Inspired Tina Fey’s First-Ever Screenplay (Showbiz Cheat Sheet)

Jacoby, Cortland (September 1, 2021) | The ‘Mean Girls’ Ending Was Supposed to Be Much Darker (Showbiz Cheat Sheet)

Spencer, Anthony (August 30, 2021) | The Surprising Way Tina Fey Inspired ‘Mean Girls’ (The Things)