Manchester by the Sea (2016) Script Review | #65 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A realistic and devastating portrayal of grief that also happens to be funny.

Logline: A depressed uncle is asked to take care of his teenage nephew after the boy’s father dies.

Written by: Kenneth Lonergan

Pages: 112

Scenes: 212

Manchester by the Sea might be the most devastating portrayal of what it feels like to live with depression and to punish oneself with the burden of guilt. It’s certainly the most realistic, refusing to tidily wrap up and resolve the trauma that haunts the protagonist of the screenplay. Here is a truth: Sometimes, these issues that weigh us down can linger for years. Sometimes, as much as we would like a happy ending, there isn’t one. Just, perhaps, a glimmer of hope.

Kenneth Lonergan weaves a rich story around Lee Chandler, who lives in a self-imposed exile following the death of his children in a house fire that, even though it was not his fault, he feels directly responsible for; the guilt hollows him out. But his humdrum existence is jarred with the news of his older brother’s death, and that he has been appointed as his nephew’s guardian. Lee reluctantly returns to his hometown, Manchester-by-the-Sea (from where the title comes), trying to figure out what to do for his nephew, Patrick, while wrestling with the memories of what drove him away, given in flashback.

The flashbacks serve as the screenplay’s B-plot, starting on page 14 and running all the way to page 79. It serves multiple purposes: It fleshes out Lee’s relationship with big brother Joe (deceased in the present), his relationship with Randi (ex-wife in the present) and their children, and is generally just a different person altogether. The A-plot, set in the present, focuses on Lee navigating the new circumstances. Lonergan structures the flashbacks in a contextual manner, where a memory is triggered by a line of dialogue or a situation— the scene when Lee is told about Joe’s Will is contrasted with the flashback of discovering his house on fire and his failed attempt to shoot himself in the head. Without using words, Lonergan conveys precisely why Lee finds it difficult, even impossible, to be a father figure to Patrick: It reminds him of how he failed his own children.

How do you write a robust screenplay about death, grief, guilt, and PTSD? Manchester by the Sea offers a reliable blueprint on how not to go about it.

In a typical script, Lee would struggle to fulfill Joe’s wishes but by the end, he would make peace with his demons; maybe he’d even get back together with Randi if she wasn’t remarried, or he’d find a new partner; and he’d step up in the end. It would also probably be told somberly, and seriously. You can’t laugh about death and grief! That’s not right!

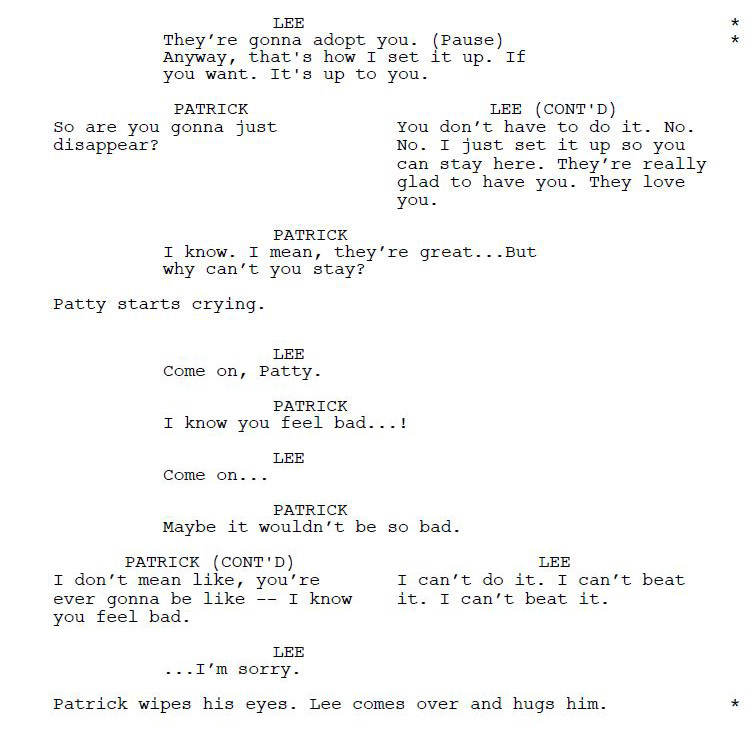

Lonergan, on the other hand, does the opposite. Yes, Lee does struggle to fulfil Joe’s wishes in this script, but in the end, he doesn’t find a way to make complete peace and step up. Instead, he finds another guardian for Patrick— family friend George— who will adopt the boy while Lee handles the money. He does, however, promise to stay in his nephew’s life but he cannot find a way to be a father figure to him because the guilt is simply too much. Lee certainly does not find a way to make peace with his grief and he definitely does not get back together with Randi, who has not only remarried but has had a baby— an announcement that really breaks Lee’s heart. When Randi tries to find a way to give absolution to Lee, he doesn’t take it (a moment that ends up being the Low Point of Act Two), in an exchange that is heartbreaking to witness.

And then there’s the other thing: It’s funny! Sometimes, morbidly so, which only makes everything even more realistic. Lots of it stems from misunderstandings and clashes, other times, it results from reactions. Have you ever been to a funeral and you know you should not be cracking jokes, but you do? It’s like that. In the process, Lonergan captures something accurate about dealing with death and grief: No matter how devastating, the world keeps on turning. Look at the scene when Patrick’s friends come over to be with him and end up arguing about the merits of Star Trek…

[insert]

… or how Patrick juggles between two girls, Silvie and Sandy, and tries to rope his uncle into keeping Sandy’s mother company while he tries to get laid.

[insert]

Or the scene, for my money, when Lee and Patrick have their first argument over a misunderstanding.

The result is that it not only feels original, it feels realistic because it is realistic, and is more affecting for it. Sometimes, the best way to avoid writing cliches is to go in the opposite direction.

Lonergan, to me, writes some of the best dialogue put to screen, though he doesn’t seem to get mentioned in the same breath as, say, Aaron Sorkin or Quentin Tarantino. I think that’s a grave oversight. The dialogue is very much a star of Manchester by the Sea. It abstains from flashiness but carries a natural cadence and rhythm that feels simultaneously real and uncomfortably intimate— which is why it can switch from painful to painfully funny in a beat. Given that Lonergan has a background in theater (and a Pulitzer Prize nomination, too), it makes sense that his dialogue has all the crackling energy you’d expect from a playwright.

The ending of the script differs from ended up in the film. In the script, it concludes with a final flashback on the boat, a trip in which everyone is there, and times were happier; in the film, it ends with just Patrick and Lee on the boat.

I don’t think it was a mistake to remove that flashback; by keeping it on uncle and nephew, there’s a thematic closure that the flashback might not have provided. But there is a piece of dialogue that Lonergan has in the script that doesn’t make it in the film about how everyone wants Lee to get better and he doesn’t— I presume Lonergan removed it because it is similar to his earlier confession to Patrick that he “can’t beat it” on page 109, but I wish he had kept it because it captures something true about how others respond to your pain. Sometimes, recovery doesn’t happen as fast as others want it to happen.

Manchester by the Sea was the fortunate product of accidental timing. Prior to this, Lonergan had gotten out of a grueling and miserable time on his last film, Margaret. Matt Damon, who starred in that film, approached Lonergan with an idea he’d been kicking around John Krasinski, about an “emotionally crippled handyman,” and asked him to help flesh it out. Whether Krasinski intended to direct it, I don’t know— but there’s a possibility he and Damon got Lonergan involved in order to shake him out of the doldrums. Whatever the reason, it worked— except Damon and Krasinski dropped out due to their schedules, and Lonergan took over.

It took him three years to get to a version of the screenplay that Lonergan was happy with; the writer-director said in an interview that the original draft was “written straight through” but only came together and started working once he chose to use flashbacks to present the relationships. Either way, it netted Lonergan a much-deserved Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, and proved that cinema very much needed and deserved Lonergan’s contributions. May he write at least one more picture in his lifetime— the work of artists like Kenneth Lonergan is too precious to deprive the world of enjoying.

Notes:

Fear, David (February 1, 2016) | ‘Manchester by the Sea’: The Story Behind Sundance 2016’s Best Movie (Rolling Stone)