The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) Script Review | #76 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

How Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens adapted the unadaptable, and changed the course of cinema and the fantasy genre.

Logline: After inheriting a mysterious ring from his uncle Bilbo, the hobbit Frodo Baggins must leave his home in order to keep it from falling into the hands of its evil creator, embarking on a journey with a fellowship to take the ring to the only place it can be destroyed: Mt. Doom, right in the heart of the enemy’s land.

Written by: Fran Walsh, Phillipa Boyens, & Peter Jackson

Based on: The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

Pages: 118 (Theatrical Edition); 172 (Extended Edition)

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring holds a special place in my heart. It’s the film that ignited my love of cinema, and it was also the first screenplay that I read. Much of my style, approach, and thought process concerning the craft of scriptwriting can be traced back to the first installment in the blockbuster adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary trilogy. I thought I’d learnt everything the script had to offer but revisiting it, nearly twenty years since I decided to write screenplays, has proven me wrong. My respect for Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Peter Jackson has only increased, for the trio have accomplished a task as seemingly impossible as Frodo Baggins’s quest: It manages to bring Tolkien’s world and characters to the big screen in a bold and exciting way, and, to people like me, makes Middle Earth accessible and welcoming. Even in hindsight, it still makes you wonder: However did they make a movie out of The Lord of the Rings?

Much has been said and written about The Lord of the Rings— the internet fandom is rife with detailed analyses and breakdowns, so I’m going to avoid that and focus entirely on what makes the screenplay so good. I’ll also be focusing on the first part without dwelling on The Two Towers or The Return of the King.

First, the screenplay works as a movie and stands on its own feet. This matters because it’s a debate that still rages today. While the script is faithful to the spirit of Tolkien’s material, it avoids being slavishly devoted to it; the books are episodic, stuffed with poems in every chapter or the other, and decidedly slower in pace. That meant eliminating characters like Tom Bombadil, Glorfindel, and Glóin; cutting out adventures in The Old Forest and an encounter with the Barrow-wights; and definitely throwing out all the poems and other slower scenes. Some of this stuff does end up on the Extended Editions and I’d argue that they are closer in tone with the book than the other scenes; yet, somehow, it doesn’t work as well. To me, anyway.

The downside, though, is that The Fellowship of the Ring— and the trilogy, for that matter— feels closer in tone to a swords-and-sandals affair. More regrettably, the spotlight gradually swings away from the four Hobbits once the Men, Elves, and Dwarves enter the game. Unlike in the books, the Hobbits seem to be much more helpless without the aid of characters like Gandalf or Aragorn. Which, to me, is a great pity; the Hobbits have always been the most interesting aspect of the story, and up until pages 49-50, during which the four were relying on their own wits to evade the Black Riders, the story works beautifully. But after Aragorn steps in, they are somewhat diminished. Perhaps that’s one reason why the late Christopher Tolkien was unhappy with the adaptations.

Incredibly, I cannot find a copy of the theatrical version of the screenplay in PDF format anywhere! Every site hosting the screenplays are those of the Extended Edition, which does not help— the Extended Edition screenplay is 178 pages; the theatrical version screenplay clocks in at a shockingly short 118 pages!

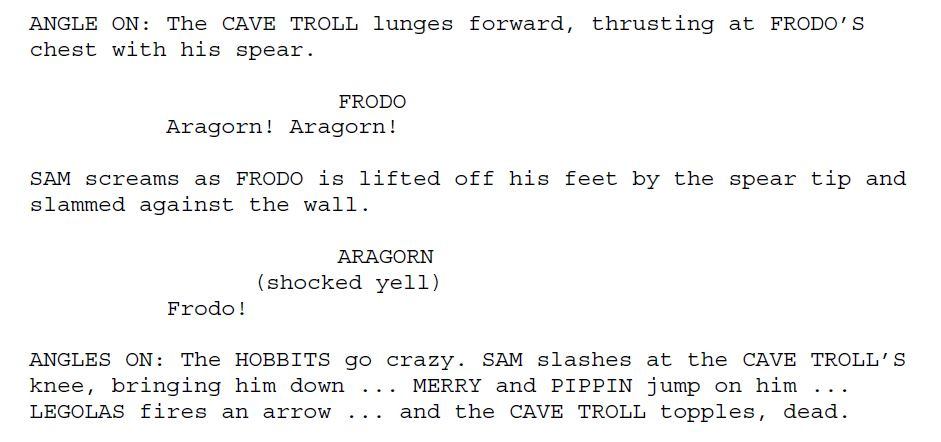

No, really, 118. That’s because the trio of writers balance macro and micro details without overdoing either, resulting in battle scenes that are described only briefly on the page but span out for many minutes in the filmed version. The Cave Troll fight, for starters, only adds up to 1.5 pages; on screen, it lasts between 5-6 minutes.

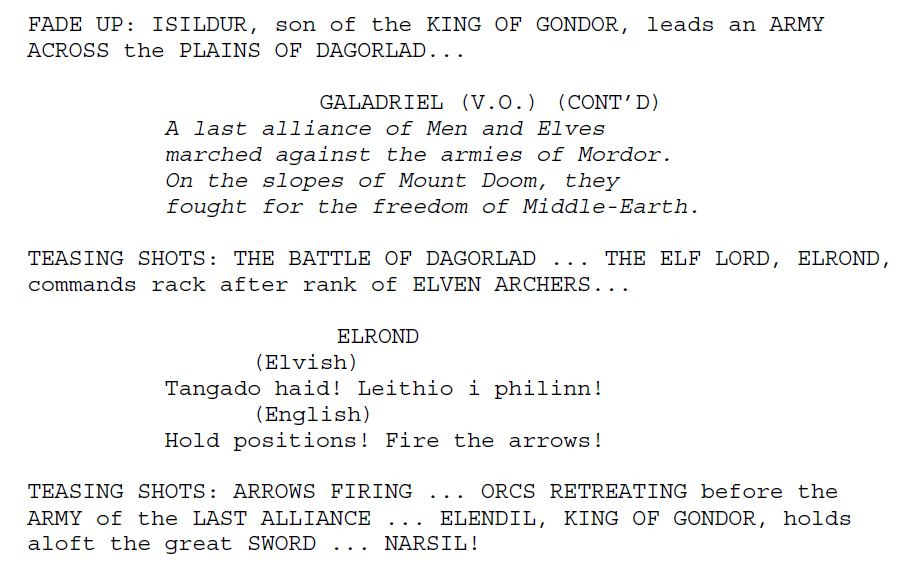

The same goes for the Battle of Dagorlad, which simplifies the action to a line each.

And the duel between the wizards, Gandalf and Saruman…

Still, they achieve in conveying the sheer scope that they are aiming for. More importantly, they draw you into Tolkien’s world without his poetic descriptions at hand.

The script can be broken into two halves. The first half centers around Frodo and his eventual arrival at Rivendell, where he thinks the Ring will be safe; the second half follows the Fellowship on their trek to Mount Doom. Had this been made into a single film, the Midpoint in Fellowship of the Ring—the Council of Elrond— would have been the end of Act I.

Many films have gotten into the habit of breaking up their stories into two parts, ostensibly to get more bang for their buck— including, ironically, The Hobbit (which got three). Among them include The Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Twilight, The Hunger Games, Divergent, Avengers 3 (before it became Infinity War and Endgame, it was titled Infinity War: Part 1 and Infinity War: Part 2) and lately, Fast X, and Mission: Impossible 7. Yet most of them suffer from the same problem in which the story ends up feeling incomplete, no matter how long it runs. The Fellowship of the Ring sidesteps that problem by standing on its own while signaling that it is part of a larger story. It’s got a sense of completed arcs while setting up what is to follow.

In an interview, Jackson said:

“We didn’t feel we wanted to end with a cliffhanger because I didn’t want people walking out of the cinema with a feeling of anxiety. That wouldn’t have been a satisfying experience. If you were releasing your second movie three or four months after the first, you could probably get away with that, but a year we thought was too long to leave people in that position. But also we had the problem, or fact, really, that the story of The Lord of the Rings is about Hobbits who travel to Mount Doom to destroy a ring inside a volcano, and we know that they’re not going to get to Mount Doom at the end of this film; they’re not going to get there until the end of the third film. So that’s the basic problem as well. Whatever you do, you’re telling a larger story that has no conclusion at the end of The Fellowship of the Ring, so before we had written a word of the script we constructed a new ending built around the character of Frodo that will hopefully be emotionally satisfying.

The breaking of the Fellowship was clearly the climax of the book and the film, and that had to have an emotional resonance for Frodo. That’s really what we based the plan around when we devised how to end the film. Frodo needs to decide that he doesn’t need the others or, more than that, that the others pose a danger to him, because the ring is starting to exert power with the people around him. That’s really the climactic moment in the film, and we thought it was very important that when Frodo makes a decision and goes on alone [with Sam trailing behind] at the very end, that you feel good for him, you feel he’s courageous, and that there’s some real hope now.”

If you need to tell one story over two parts (or in this case, over three), make it feel complete in a sense— it should have a beginning, middle, and an end.

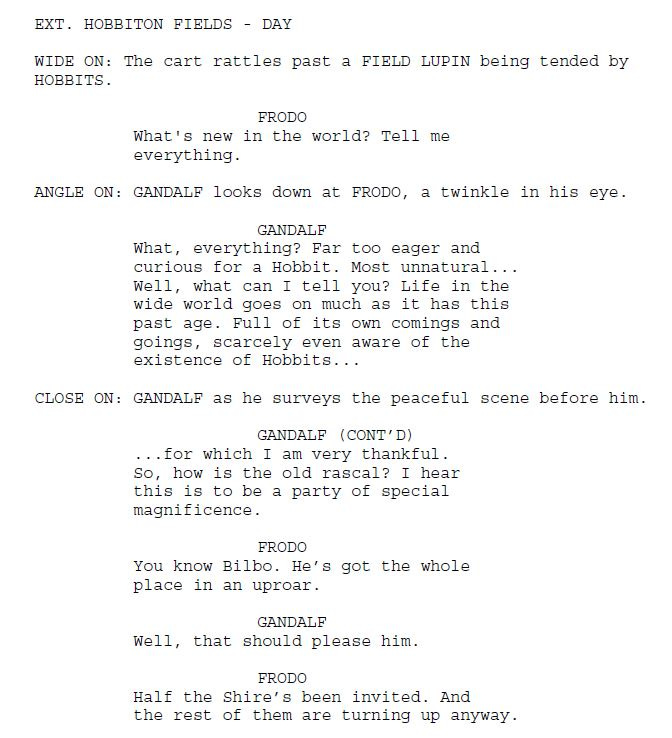

Something that sets the scripts apart from the books is the amount of humor incorporated into the proceedings. Reading Tolkien’s books don’t make you chuckle; reading this screenplay does. A little levity goes a long way in capturing your readers and helping to buy into the world. It owes its comic relief primarily to Merry and Pippin, and later Legolas and Gimli; while Gandalf being curmudgeonly is its own form of humor.

No matter your genre, whether it’s fantasy or thriller, find ways to inject humor that feels organic. It’ll improve your screenplay immediately.

How to Write an Effective Prologue like in The Lord of the Rings

The success of the screenplay— and subsequently, the film— lives or dies depending on how effective the prologue is. On paper, it lasts six pages, and rapidly sets up the world, the backstory, the kind of characters to expect, the central conflict, and the tone of what to expect.

Unbelievably, it draws its influences from, of all things, the James Bond franchise! Peter Jackson’s touchstone for the prologue was Thunderball, and his objective was simple: he wanted to “blow people away in the first five minutes… which buys you that little bit of story set-up time during your first act.” It also gets a lot of heavy exposition out of the way while making jaws drop. I can personally testify to the success of the prologue: I read and watched it, and both times, I was hooked.

But a prologue cannot simply be a dumping ground for exposition and pretty visuals. It needs to be dramatic. In fact, one YouTube user cleverly analyzed the effectiveness of the prologue in the live-action movie versus the prologue in Ralph Bakshi’s 1977 animated adaptation, and made the point that the prologue functions as its own story, unfolding with twists and turns and surprises, leaving a few mysteries that are answered later (such as why Isildur didn’t destroy the Ring, which foreshadows Frodo’s fate in The Return of the King). It’s innocuous but even having the first words of dialogue being that of Galadriel speaking in Elvish immediately sets the tone, followed by its translation: “The world has changed.”

And for writers who (like me) get stumped at how to write a prologue, simply do what Walsh, Boyens, and Jackson do: Cram it all under one slugline called “Prologue.”

The Council of Elrond

If you want to learn how to adapt a book for a screenplay, ‘The Council of Elrond’ is a perfect opportunity to exercise your craft: Turn 43 pages of a book chapter into 5 pages of a screenplay.

Had the writers adapted this chapter as it was written by Tolkien, they’d have ended up with an entire movie of its own. Yet it’s also a crucial chapter that provides much needed information, backstory, and stakes.

In the end, this is how Walsh, Boyens, and Jackson adapted ‘The Council of Elrond’ chapter for the screenplay:

They drew mainly from the last few pages of the chapter and some more from the following chapter, ‘The Ring Goes South’;

They repurposed a good chunk of the material— such as Gandalf describing Saruman’s treachery— into earlier scenes, thereby avoiding characters describing entire sections;

They eliminated information about the events of the Dwarf kingdoms and Glóin;

They eliminated the fate of the Elven rings as well as Minas Morgul;

They eliminated Aragorn’s tale concerning Gollum is cut, as well as Gollum’s imprisonment at Mirkwood (in the script, it’s implied that Sauron released him);

They eliminated Gandalf’s narrative about Dol Guldur;

The crucial bits of Elrond’s story—not his entire history—is used in the Prologue.

Some might take umbrage at the brutal omissions and changes made, but that’s to be expected. You can’t please everyone, and at the end of the day, if the changes you make are done in service of crafting a strong scene and strong story overall, even most purists will find it too hard to get mad.

The style of writing in this screenplay is an amalgamation between the more modern way of scriptwriting— in which it feels like a book— and the older style of scriptwriting—in which it feels like a blueprint replete with camera directions. The latter is frowned upon severely if you are not going to be the director, but I would add that used here, it conveys the scope and scale that the writers are aiming for.

How Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens Adapted The Fellowship of the Ring

The adaptation process began in April 1997, as Jackson and partner Fran Walsh started with a 90-page outline of the three books; over the next few years, they’d rewrite the outline multiple times, seeking to capture the essence of Tolkien’s story. As Jackson said,

“… The books themselves are not structured to easily equate to a screenplay. Most of the first book is a gentle stretch of journey and masses of exposition… For the movies, we will have to make motivations a little tighter and more urgent. We have to focus on The Ring, Sauron, and the threat to Middle-earth. The way that we often write is to provide different layers over subsequent drafts, i.e., write the villain in one draft, get that working, then go back over the scenes and humanize him in the next draft.”

Although the writers initially wrote two 150-page scripts for Miramax, plans changed once the project was taken over by New Line Cinemas. The 300 pages were divided into three 110-page screenplays; each roughly adapting the narrative corresponding to Tolkien’s books. They’d continue tinkering with the scripts all the way until filming began, taking every opportunity to tighten the screws on the narrative.

Jackson raises an illuminating point about how they approached internal and external conflicts in The Fellowship of the Ring:

“The external conflict is the fact that there are other forces in this world that also want the ring. The Orcs and Uruk Hai from Isengard… Saruman sends them to capture the Fellowship. So we definitely built that up, and we created a character of one of the Orc-like creatures, a character called Lurtz, who’s not in the books. It’s the only time in the movies that we’ve created a character that Tolkien didn’t actually write about. Because we thought we needed to personalize the leader of this band of Orcs. It’s Saruman who is the villain, but he doesn’t leave Isengard, he dispatches his guys to go get the ring, so we wanted to actually create a character of the leader of this group who goes after the Fellowship. That helps us beef up these external forces of opposition that lead toward the climax, which is this battle on the slopes of the River Anduin just before the Fellowship breaks.

“The other strong force at work is the internal conflict where the ring has this incredibly seductive attraction to other people and particularly men, Aragorn and Boromir feeling it stronger than the Hobbits. That is providing just as much jeopardy to Frodo as the Orcs that are pursuing them. We definitely used those two external/internal forces concurrently to crank the climax up into something that’s pretty powerful.”

Much has been said about The Lord of the Rings that it becomes very hard to add anything new and worthwhile to the conversation. But I will say this: The Fellowship of the Ring still generates conversation and is on the WGA list because it works as a movie and accomplishes the difficult task of generating excitement for two more installments. It’s an excellent template for how to adapt a book as a screenplay, especially those in the fantasy genre.

Above all: Create compelling questions in the reader’s mind, even doubts so that it keeps the reader hooked, before strategically revealing the answers. Don’t frontload all the exposition about a fantasy world in the fear that they will not understand what’s going on. It is easier to ask for permission to indulge in waiting a little while longer than it is to bore them with dull exposition!

Notes:

Sibley, Brian - Peter Jackson: A Filmmaker’s Journey (2016)

Bauer, Erik (December 16, 2014) “It’s just a movie” – Peter Jackson on The Lord of the Rings | Creative Screenwriting