Lost in Translation (2003) Script Review | #19 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Profound in its simplicity, moving in its poetry, Sofia Coppola creates a mesmerizing portrait of finding a rare connection when feeling lost.

Logline: The young, neglected wife of a photographer and a washed-up movie star shooting a TV commercial cross paths in Tokyo and form an unlikely bond.

Written by: Sofia Coppola

Pages: 75

Scenes: 118

There isn’t a dull moment in Lost in Translation. Here is a script that is unafraid to be meditative, contemplative, maybe even melancholy, as two lonely people find each other in a country that is not their own, and build a rare and precious connection. What Sofia Coppola has written is a love story, though not in the romantic sense of the word.

These two people are Bob Harris and Charlotte. By coincidence, both currently happen to be staying at the Park Hyatt in Japan at the same time. Bob is a washed-up actor; he’s in Tokyo to shoot a series of commercials for Suntory Whisky (a real brand, by the way). Charlotte is tagging along with John, her photographer husband, on one of his assignments. Bob is miserable. He hates what he does for a living; meanwhile, the faxes and phone calls with his wife, Lydia, suggests that he has grown distant in their marriage. Charlotte feels aimless and lost; her marriage, too, hints at unease and distance.

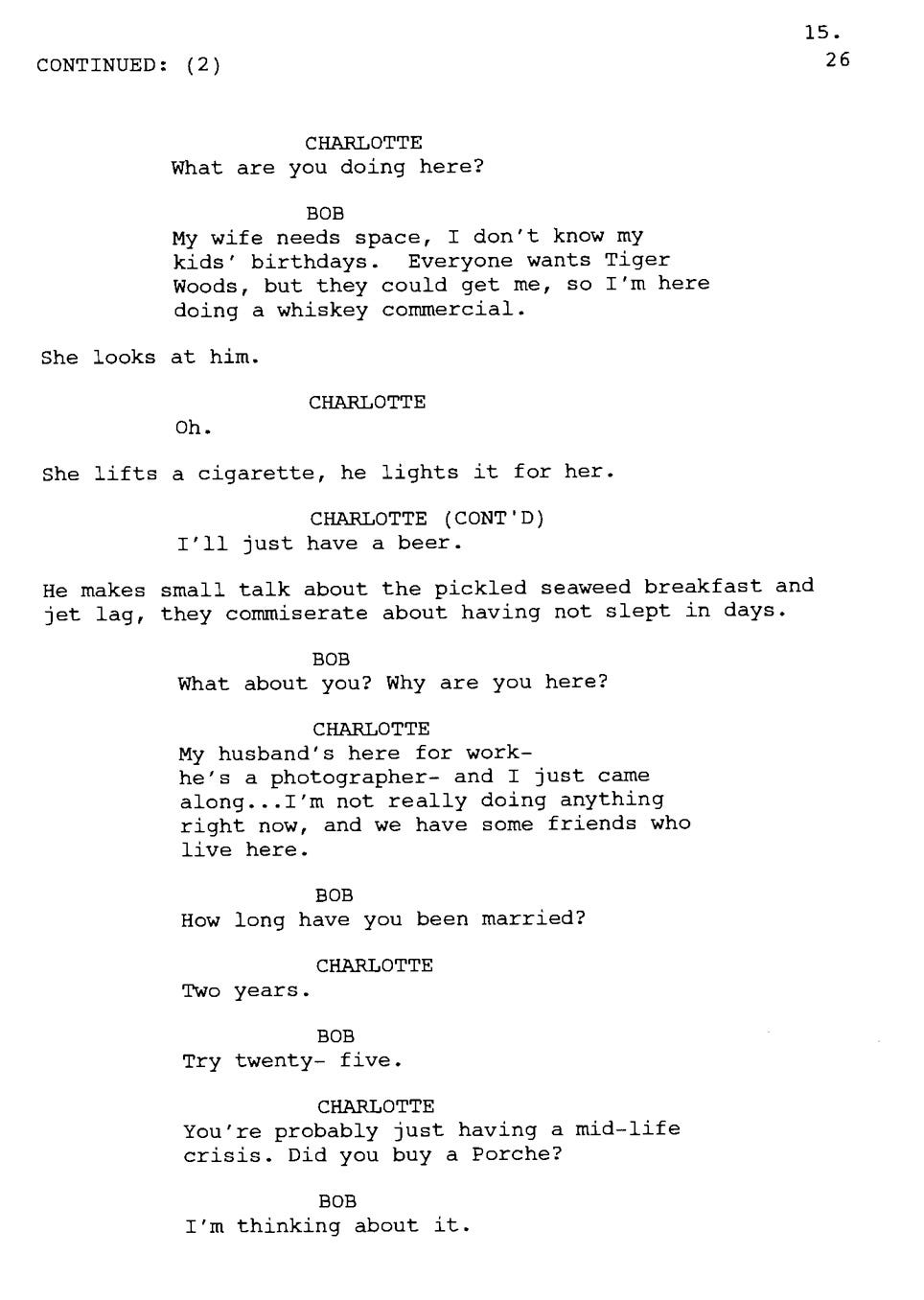

Unable to sleep, Bob and Charlotte cross paths one late night at the bar. They chat. About their lives, their insomnia (this happens on page 15).

When John is sent to Osaka on assignment for five days, Charlotte invites Bob to a party thrown by some of her friends (this happens on page 34). This brings us into Act 2 as Bob and Charlotte spend the next five days wandering around Tokyo (although Charlotte takes a solo trip to Kyoto) and having a good time together.

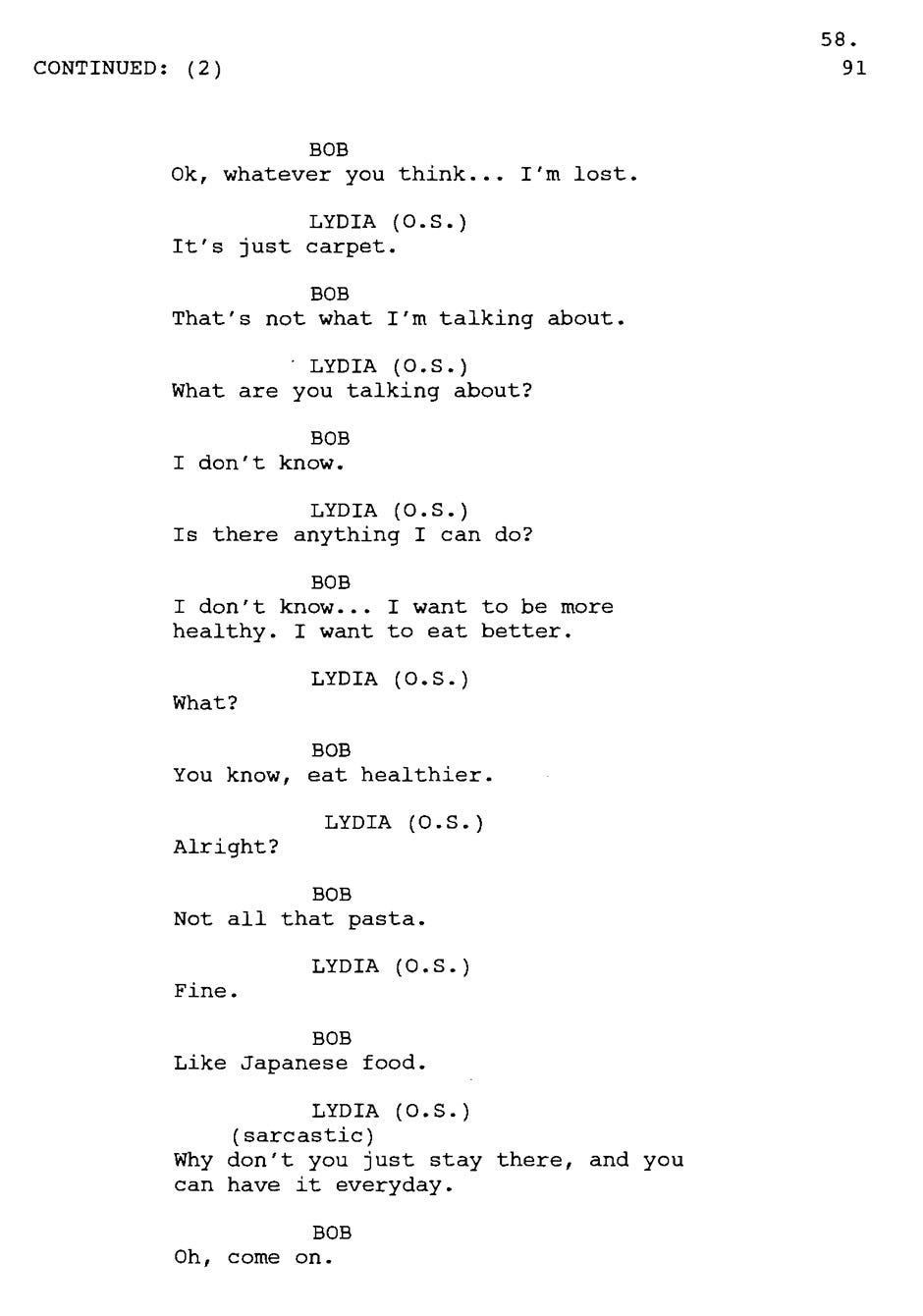

The title, Lost in Translation, has literal and metaphorical translations. Literally, it refers to feeling culturally alienated in a place you don’t feel like you belong in; it can also refer to the feeling of alienation from people you love. A prime example occurs on page 58, when Bob tries and fails to express to Lydia how lost he feels.

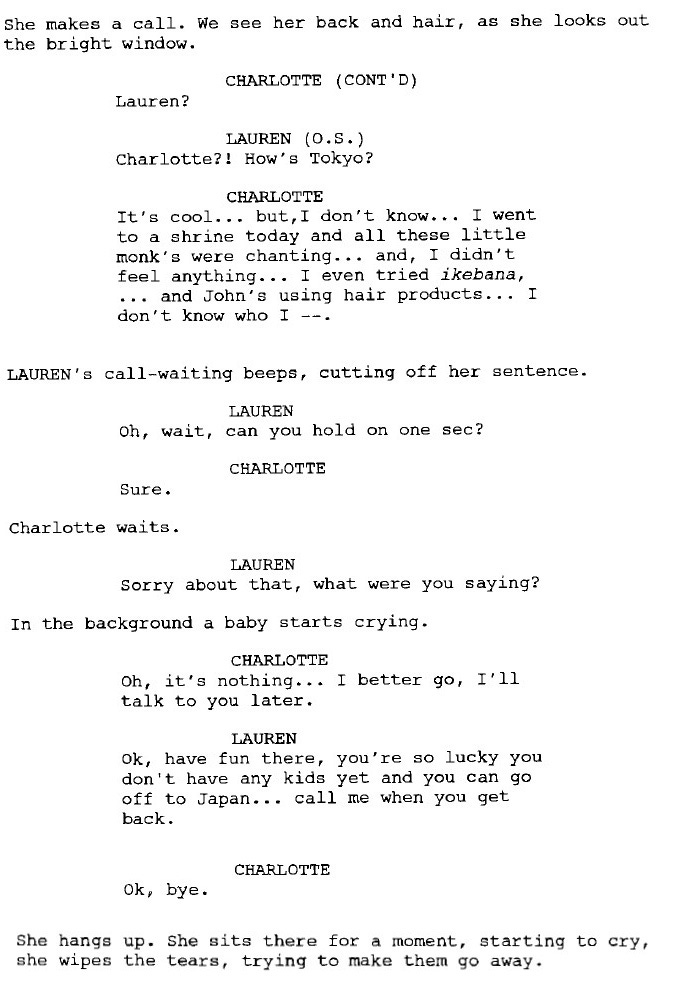

Charlotte has a similar experience earlier in the script on page 29-30 when she calls Lauren but finds herself unable to express her doubts and uncertainty; perhaps out of fear of not being understood. After all, there’s nothing more that we are afraid of than being misunderstood by those close to us.

That might explain what brings Bob and Charlotte together. Here, in another country, among strangers, they are able to share and show off aspects of themselves that they might otherwise have been uncomfortable revealing. Instead, now they have a chance to be liberated versions of themselves; idealized versions, even. Take, for instance, the scene at karaoke; in the script, it’s a brief moment, but in the film, it’s a chance for Charlotte to show off a flirty side of her that was missing in the scenes with John.

Compare how the karaoke scene was written to the finished version below:

For a few brief days, Bob and Charlotte are able to create a world together for each other; over those few days, they go through all the different parts of a relationship, from the ‘meet-cute’ to attraction and interest, even a ‘break-up’ before reconciling. While Act 1 (pages 1-34) alternate between Bob and Charlotte trapped in their separate loneliness, the bulk of Act 2 focuses on the days they share together.

Day 1 – That night, Bob and Charlotte accompany ‘Charlie Brown’ (based on a real person that Coppola knew) and ‘Bambi’ to a party before they get chased out and wind up in a karaoke bar.

Day 2 – In the morning, Bob and Charlotte have breakfast together but they both feel awkward. However, that night, they hang out in Bob’s room, share their fears and insecurities, and fall asleep watching La Dolce Vita.

Day 3 – Bob skips an interview to go around the city with Charlotte; the latter is especially thrilled with the way he fusses over her minor toe injury when he takes her to the hospital.

Day 4 – Charlotte goes to Kyoto while Bob fulfils his agreement to appear on a popular Japanese talk show; feeling lonely, Bob sleeps with the red-headed singer of the band who plays at the hotel.

Day 5 – Charlotte is moody about discovering that Bob slept with the red-headed singer; Bob is irritable with her bratty behaviour. But when a fire alarm goes off in the hotel that night, they patch up and try to enjoy their last night together.

Day 6 – Bob leaves to catch his flight but not before he finds Charlotte and says a final goodbye.

A question lingers throughout the story: will they or won’t they? Wisely, the script avoids such a route; instead, it opts for something else. Something more difficult to describe or define. It’s a fleeting and tenuous connection; although on page 73, it is implied that Bob loves her and wants to tell her so. When he says the second goodbye, he kisses her. The film plays it off more ambiguously, but the love they have for each other is undeniable.

The script has very little plot, at least in the conventional sense of the word. Every scene, especially those with Bob and Charlotte, is devoted to character development and expressing thoughts and opinions, such as in Scene 76 when Bob is honest about the state of his marriage.

Although the film would play out more or less as in the script, Coppola would take advantage of the actors’ skills to allow for improvisation and spontaneity. A great example of improvisation would be the line on page 26 (Scene 36), where Bill Murray would come with a different—read: funnier— line than what was on the page.

What Murray came up with instead:

“Can you keep a secret? I’m trying to organize a prison break. I’m looking for like, an accomplice. We’d have to first get out of this bar, then the hotel, the city, and then the country. Are you in or are you out?”

For Sofia Coppola, Lost in Translation was her first original screenplay; previously, she’d adapted The Virgin Suicides. She has a writing style that is light in description but vivid in its ability to visualize the scene. In a bold move, she even avoids any dialogue until page 4. Bold.

Since this is a bilingual film, here’s how Sofia Coppola overcame the challenge of writing Japanese dialogue for an English screenplay— she simply indicated that a character is talking in the language as an action line.

Lost in Translation was inspired by Coppola’s time living in Japan— allegedly, the character John is a stand-in for her then-husband, Spike Jonze, and the actress character Kelly is rumored to be based on Cameron Diaz. The Bob and Charlotte characters were also influenced by Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep. Like Charlotte, Coppola was feeling disconnected and isolated as she entered her 30s. while traveling, working, and shooting music videos, she found herself concocting a romantic story about two culturally alienated Americans. She wrote the script in 6 months, jotting down notes and little stories on pieces of paper and ‘adapting’ them for a screenplay; she also videotaped whatever she saw in Japan that inspired her (remember, this was before smartphones became ubiquitous). After she got 20 pages down on paper, she showed it to her brother, Roman Coppola, who supported what she had written. For the remainder of the script, she returned to Tokyo to be inspired further, especially by the Park Hyatt, which is the main setting of the story.

Unlike many writers, Coppola did not spend a lot of time rewriting or overthinking the script. This might be due to her intention to direct Lost in Translation herself, so she would be able to provide more guidance on set than if she handed it over to someone else. As she said in an interview, it’s “better just to go in the dark and figure it out as you go.”

Another gutsy move that most first-time writers should normally avoid is writing with a specific actor in mind; in this case, Coppola wrote it with Bull Murray in mind. It was a risky gamble, and until the day of shooting, the team did not know whether Murray would turn up or not.

Lost in Translation only lasts 75 pages, a page count that did not sit well with financiers; to prevent any one person having veto control, Coppola and her ICM agent, Bart Walker, licensed the distribution rights in various overseas territories individually, raising enough pre-sales money to avoid a single controling territory or US domestic distributor have majority power. But the short script is because many scenes only provide a brief description of the action and intention; a couple of lines or a paragraph or two on the page can last several minutes. Look, for example, at how the scene in which Bob is greeted by the Suntory team runs for only a few paragraphs; in the finished film, it runs for approximately one minute.

Music is an important fixture in the story, and Coppola even gets specific about the types of songs to play. Of course, this always changes depending on new suggestions and especially on the budget; the purse determines the availability of song choices. For instance, the script has Bob singing “I Fall to Pieces” at karaoke, whereas in the film, it would be “More Than This.”

One concern that has been raised is the allegation of racism in the way in which Coppola depicts the Japanese—see, for instance, the scene where Charlotte reacts to the band on page 11.

But then wouldn’t all customs unknown or different seem, for lack of a better word, unusual to outsiders? I am willing to argue that Coppola was simply portraying the Japanese as she saw the culture without meaning to be xenophobic or insulting.

Writing what you know is a common theme that has been popping up across entries in the WGA’s list of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century, especially when starting out. For Sofia Coppola, Lost in Translation won her the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (beating out Finding Nemo, the only other film in this category to make the cut for the WGA list), as well as the Golden Globe and Writer’s Guild of America Award in the same category. What could have been a bland travelogue is instead a sweet if sad depiction of what it’s like to feel lost and adrift when one is young, as well as the magic and wonderment of making a precious connection in unexpected places. Even if it lasted five days, we know that Bob and Charlotte will carry this time with them until the day they die. We, too, will remember and marvel at this miracle.

Notes:

Chumo II, Peter N. (March 10, 2015) | Honoring the Little Moments: Lost in Translation (Creative Screenwriting)

Nayman, Adam (September 26, 2023) | We’ll Never Know Everything About ‘Lost in Translation’ (The Ringer)

Thompson, Anne (2003) | Tokyo Story (Filmmaker Magazine)

Gokhale, Stuti (August 1, 2023) | Lost in Translation: Is the Story Based on Sofia Coppola’s Life? (The Cinemaholic)

Topel, Fred (March 11, 2004) | Sofia Coppola on “Lost in Translation” (Screenwriters Utopia)

Diaconescu, Sorina (September 7, 2003) | An upstart, casual but confident (LA Times)