Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) Script Review | #72 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

How the Coen Brothers capture the struggles of a musician in this haunting and melancholy screenplay.

Logline: In Greenwich Village in the early 1960s, gifted but volatile folk musician Llewyn Davis struggles with money, relationships, and his uncertain future following the suicide of his singing partner.

Written by: Ethan Coen and Joel Coen

Pages: 113

The more I think about it, the more Inside Llewyn Davis feels like a searing and sobering reminder about the ruthlessness of succeeding in the arts; where talent isn’t enough, where passion about your craft isn’t enough; where even hard work isn’t enough. Sometimes— and if there’s a brutal moral to this screenplay, it would be this— sometimes, you just might not have what it takes to make the cut. And that’s always the harshest truth to fall on the ears of anyone who wants to make a living doing what they love. In a winner-takes-all economy, many aspiring singers, writers, actors, and artists with big dreams and empty pockets will never hit stardom. It doesn’t matter how much you want it. Sometimes, wanting something so badly isn’t enough.

That, at least, is how I interpreted the screenplay.

Inside Llewyn Davis is the 16th script that Joel and Ethan Coen have turned into a feature, and they would know a thing or two about how tough it is out there. Although the Coen brothers command a degree of prestige and acclaim (by the time they made this, they’d won four Academy Awards, including one for Best Original Screenplay (Fargo) and another for Best Adapted Screenplay (No Country for Old Men)), they’ve never been big box-office draws (the biggest financial success of their careers was True Grit). Nor are they known by the casual filmgoer; still, they’ve been able to carve a small market for themselves, and they’ve written some truly great screenplays since they broke out with Blood Simple in 1985. That’s partly because their stories aren’t palatable or easy to sparse; nor are they easy to pigeonhole. They’ve done noir, they’ve done comedy, they’ve done crime; they’ve done a western. The only common thread running through their work is rich, complex, three-dimensional characters; moral ambiguity; and a refusal to spell out what it’s all about— perhaps born out of their love of literary classics. And, except in very rare cases, a dollop of droll humor. The Coen brothers are gifted at comedy.

Where was I…? Yes, Inside Llewyn Davis. The script was inspired by the life of folk singer Dave Van Ronk. The spark for the story was ignited by an image of Van Ronk getting beaten up in an alley, an image that makes it here and seemingly kicks off the story… until you reach the end and realise that, chronologically, it happens at the end, and everything in between the first time Davis gets punched and the second time is one long flashback. At least, I think that’s what happens. Like I said, nothing about the Coens is easy to interpret, but I figured that there’s something tragically Sisyphean about Davis getting beaten up— as if violence is just another part of the penniless existence to which he’s tied up.

Davis, by the way— Llewyn being his first name— is a volatile folk singer in the late 1960s on the scene of the Greenwich Village, New York. It’s hinted at first, then made clear though never gone into depth, that Davis was once part of a singing duo until his singing partner committed suicide. Since then, his career has been in jeopardy. He’s good, but as the music producer Bud Grossman will tell him on page 87, he’s not lead singer good.

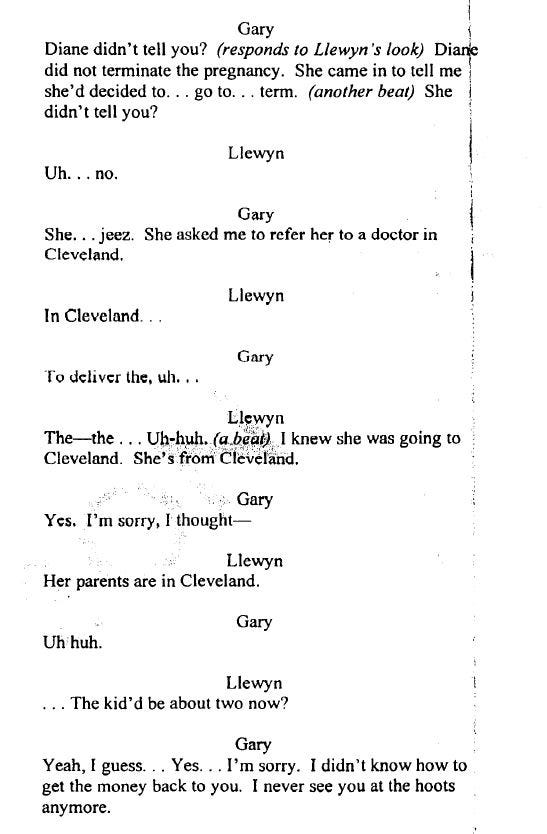

What is the plot of Inside Llewyn Davis? Strictly speaking, there isn’t one. The script follows Davis as he aimlessly moves about, crashing with other people because he doesn’t seem to have his own place. Nor is he the greatest with relationships—in one subplot, he has to scrape together money to pay for an abortion of his friend’s wife because there’s a chance that he’s the father, only to discover later that he’d paid earlier for a previous abortion but the woman had opted to keep the baby without telling him. You know what they say about show, don’t tell? Somehow, the following interaction speaks volumes about how to do it well.

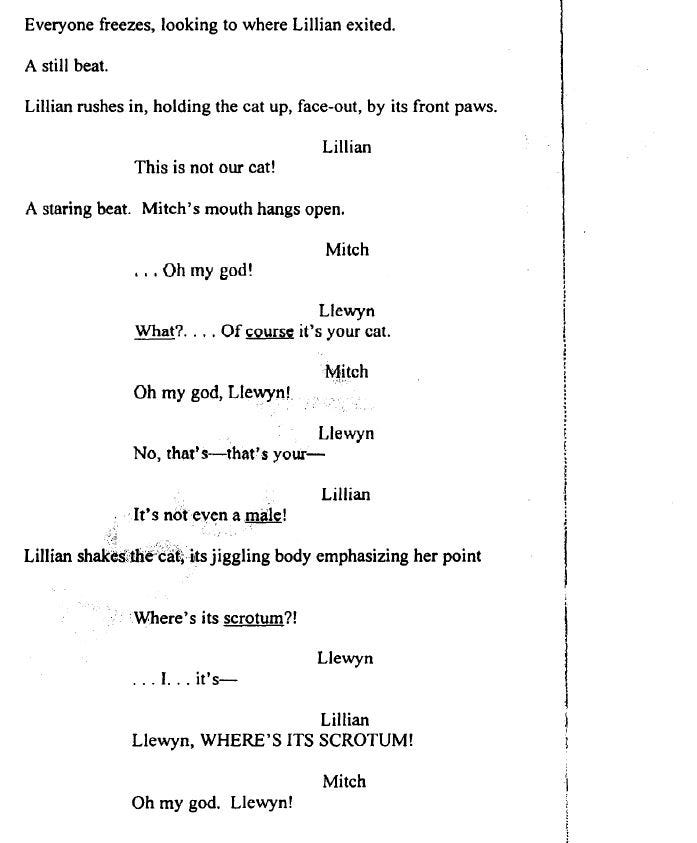

He also loses the Gorfens’ cat when it escapes into the street— not a great way to repay your hosts’ hospitality— only to find and return it until he realizes that he’s brought back the wrong cat!

Remember what I said about the Coen brothers having a great comedic sensibility? It’s on full display here— along with the cat’s lack of scrotum (I could not resist)!

In the second half, Llewyn accepts an offer to travel to Chicago with an eccentric and pugnacious man, Roland Turner. The Low Point could be considered his meeting with Grossman going nowhere, which then leads to Llewyn attempting to return to being a sailor, only for that to also sputter.

The closest comparison I can draw as a reference is to James Joyce’s Ulysses, a novel in which Leopold Bloom and Stephen Daedalus basically wander around. But what is lovely about Inside Llewyn Davis, as with most of the Coen brothers’ work, is that it avoids the well-worn cliché road. Take, for instance, the moment Davis does get his moment to showcase his talent, only to feel dejected by the lack of enthusiastic response. Or the fact that Davis doesn’t get his act together by the end of the story or attempt to turn his life around. In another story, the abortion storyline with Jean would have been the focus, especially with her husband Jim discovering the truth. Here, it’s just a sub-plot; a minor sub-plot, if you will.

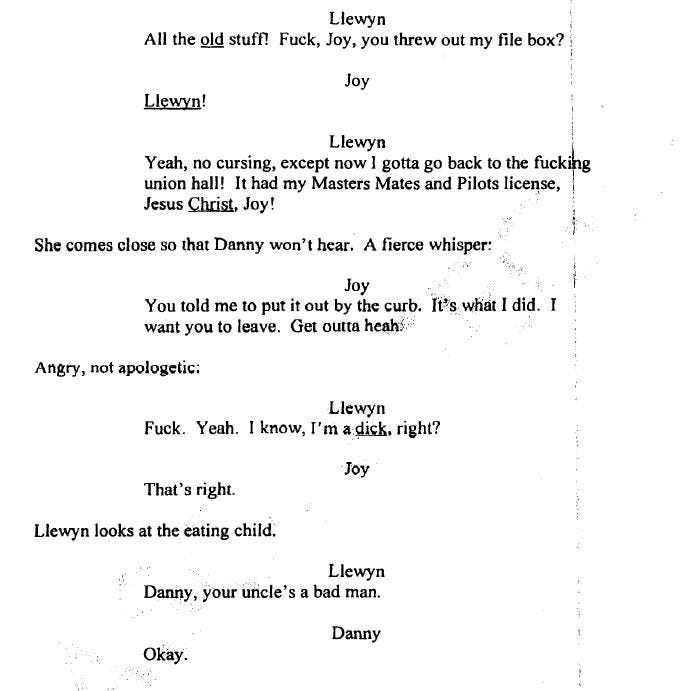

I won’t lie, this is a very depressing screenplay. Which makes the funny bits only funnier because you do get the sense that Davis is trapped in a hell that is largely of his own making— like the occasion he tells his sister to throw out a box of his belongings, only to later discover that she thought he meant everything, including his shipping license.

If you are just starting out in your career, you might want to steer clear of these kinds of stories for three reasons:

They’re not commercially appealing!

You need clout to get it made!

Most importantly: even if you fulfill the first two criteria— you need the maturity and experience to write it well.

And one would imagine that the Coens had enough maturity and experience to pull it off, as they demonstrate here.

Something that I always did wonder about scripts that includes musical bits— especially original music. Do you write the lyrics in? For Inside Llewyn Davis, the answer is no. They indicate the song being performed and leave it to talented songwriters to figure out the rest.

Make no mistake, Inside Llewyn Davis is as challenging as it gets. It’s confident and masterly, a screenplay written by two artists still operating at their best. It’s intelligent, and is great at the whole show-don’t-tell craft that makes screenplays worth reading. It’ll also make you think about its subject and themes for a long time after you put it down. This is a rare example of art— good, beautiful, wonderful art. And unlike Llewyn Davis, the Coen brothers do have talent and the capacity to work hard, because they want it. This script is the proof of it.