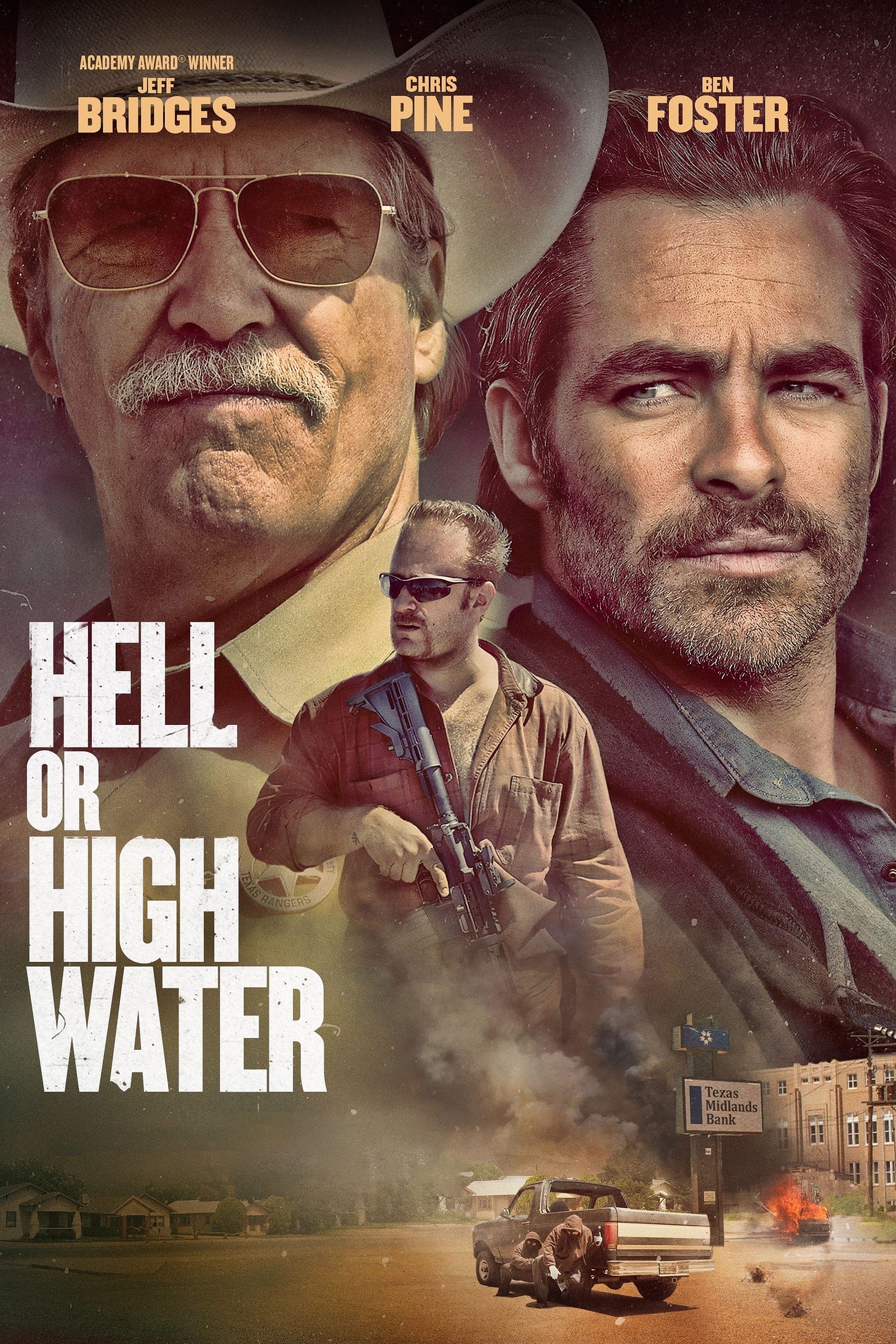

Hell or High Water (2016) Script Review | #64 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

An often taut cat-and-mouse thriller about two bank-robbing brothers and the sheriff trying to catch them before his retirement.

Logline: A divorced dad and his ex-con brother resort to a desperate scheme in order to save their family’s farm in West Texas.

Written by: Taylor Sheridan

Pages: 112

If you crossed a buddy road story with a heist thriller and elements of a western— but one that shows the consequences of flawed characters in a real drama— you’d get Hell or High Water, a bleak and nifty tale about two brothers who embark on a desperate quest that, despite its big points, doesn’t add up together all that satisfactorily. (Note: I’ve not watched the film; therefore, I’m judging the merits of the screenplay entirely by what I read on the page).

Set in the parched and dying small towns of West Texas, the Hanson brothers hit a series of bank branches— specifically, the First Texas Bank. They need the money to save their family farm, which is close to being taken away from them by, surprise, First Texas Bank (who said revenge doesn’t have to be poetic?). The scheme is hatched by the younger brother, Toby— a kind and smart man who is divorced and can’t see his children— and executed by the older brother, Tanner— an ex-con who is wild and unpredictable. But on their trail are two Texas Rangers, Marcus Hamilton and Alberto Parker. Hamilton is due for retirement but he cannot resist the lure of one final hunt before he hangs up his guns. As the paths of the Hanson brothers and the Texas Rangers converge, the outcomes become a question of fate: Will the Hanson brothers save their farm or will all this be for nothing? Will the Rangers capture the brothers, dead or alive, or will they be killed?

Hell or High Water was written by Taylor Sheridan, who has ascended to a seat at the top with other Hollywood power players in a short time. By combining his knowledge of the West with his penchant for original ideas, Sheridan has become known for tackling morally ambiguous and thorny subjects, raising more questions than answers in his stories while keeping his audience entertained. I might be a little dispirited with Hell or High Water but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have anything valuable to teach.

For instance: How do you write a screenplay where your main characters are criminals but without making them “noble” since they’re doing it for an understandable reason? How do you portray the Texas Rangers as righteous without turning them into the villains?

It’s a tricky balance but one way that Sheridan finds a fine middle ground is to withhold the characters’ motivations— especially the Hanson brothers— for as long as possible. It’s dicey. Play your cards too early, you’ll achieve the very outcome Sheridan was trying to avoid; keep your cards too long to the vest, and you’ll risk losing your audience.

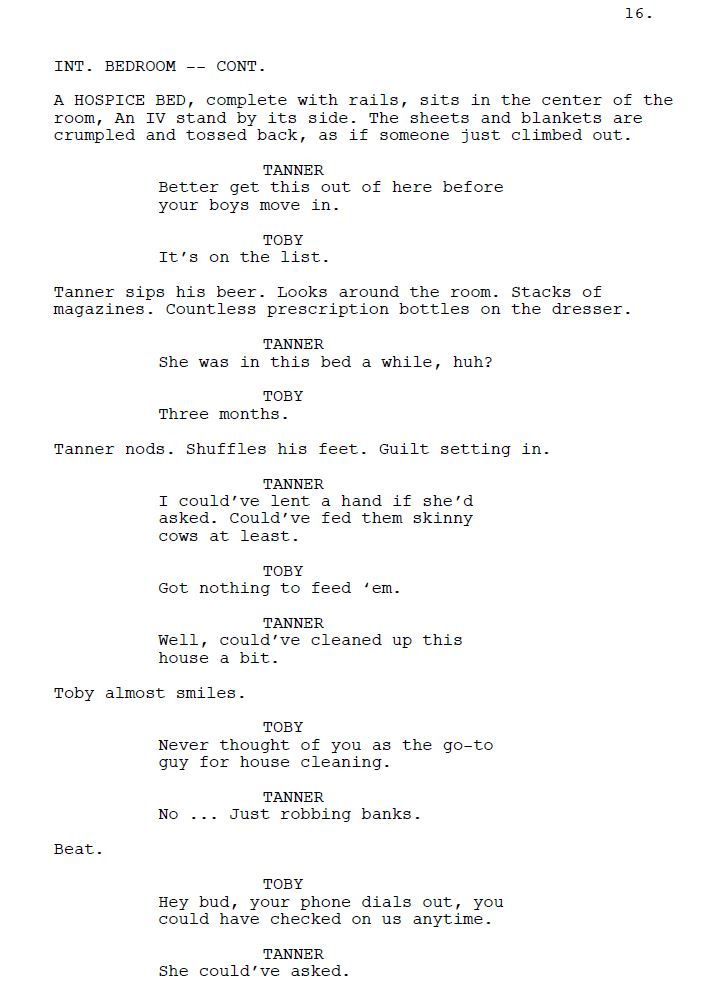

We get the first hints at the Hanson brothers’ motivation somewhere around pages 15 and 16 (the loan papers) …

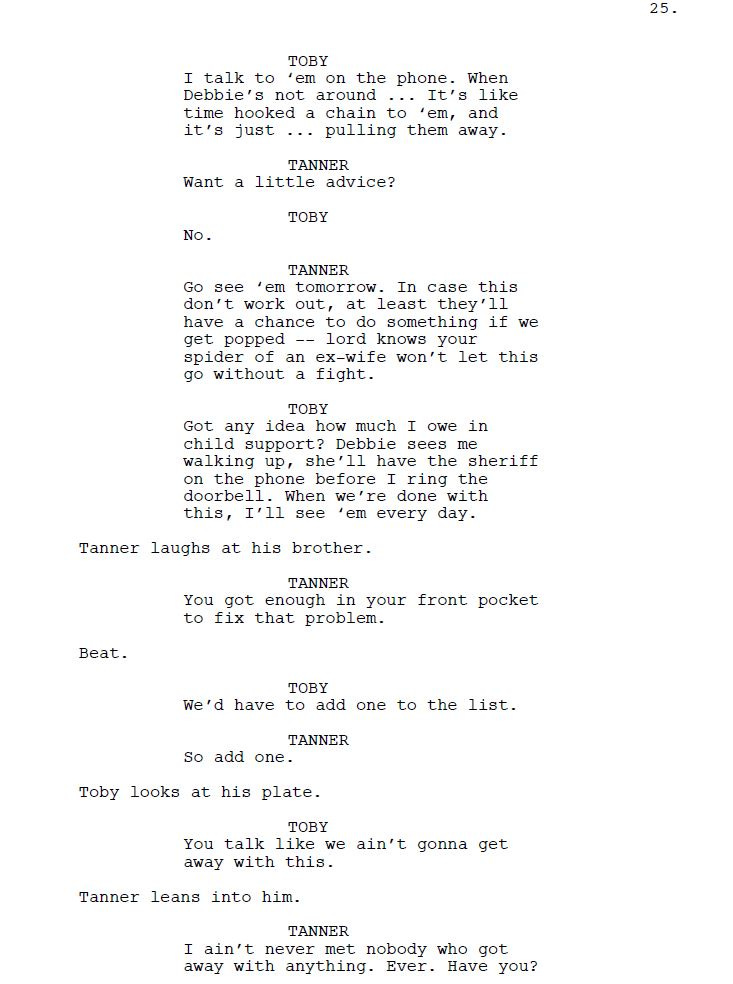

… some more on page 25 (Toby’s divorce and his inability to pay child support keeping him away from his children) …

… until finally on page 72, Sheridan unveils the real reason the brothers want to save the rundown family farm: there’s oil on the ranch, and if the bank gets the land, they’ll get the rewards of the oil.

Sheridan waits for 72 pages to divulge this information, which is a lot considering the screenplay only has 113 pages (without the cover page). It’s a gamble, but it certainly adds mystery and a deeper layer of how people driven to desperation will do whatever it takes to get out of being poor. The objective is not to condemn or glamorize, but to hold up a mirror at the world and point out that we live in a time of great inequality, one in which the Hansons fell through the cracks. Plus, by withholding that information until the time was right, Sheridan avoids the need for long exposition dumps about the oil (he claims to have an “allergy for exposition”).

If the plots in Sheridan’s screenplays feel simple, that’s by design. He looks for plots that are absurdly simple in order to focus on the character— instead of multiple skirmishes and conflicts, the robberies and the final fight is kept brief, and the scenes in between devoted to Toby and Tanner, and Hamilton and Parker. This is also partly achieved by subverting the genre, bypassing convention in favor of something different. Subversion is the gift that Sheridan likes to keep giving.

Setup – The Hanson Brothers embark on their first bank robberies and get away with it

Inciting Incident – But the Texas Rangers, Hamilton and Parker, begin to follow their trail

Act One Out – Tanner deviates from the plan to rob a bank not on the list to help Toby with child support but in doing so, threatens to expose their identities to law enforcement

Rising Action – The Hansons launder the stolen money through casinos while Hamilton and Parker keep a lookout for the next likeliest bank to get hit

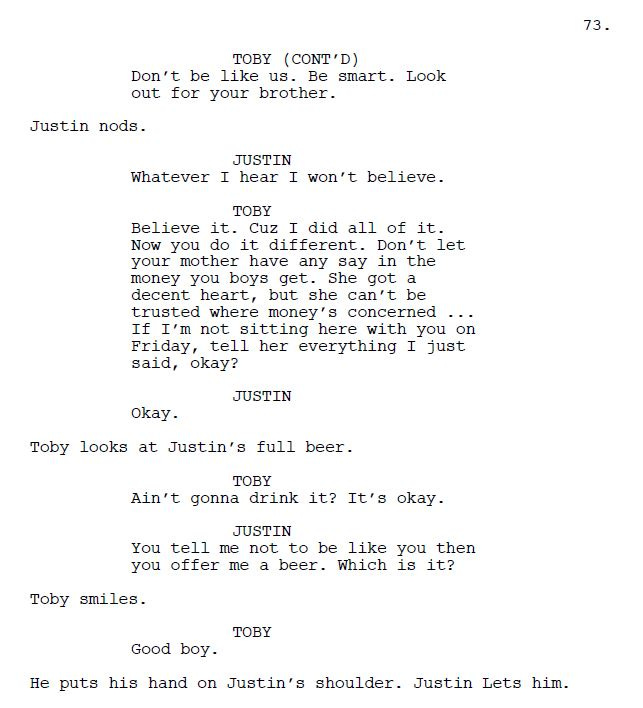

Midpoint – In a discussion with his son, Toby reveals why he and Tanner are trying to save the farm (i.e. oil) and prepare for the final bank run

Low Point – But the citizens in the bank disrupt their efforts to make the robbery uneventful and chase the brothers, forcing Toby and Tanner to split up as both enraged citizens and law enforcement hound them

Build Up – Tanner diverts their attention to allow Toby to escape, but ends up killing Parker in the skirmish

Climax – Toby flees and is able to save the farm but Hamilton kills Tanner in retaliation

Finale – A retired Hamilton confronts Toby, ending their interaction on an ambiguous promise of a showdown

Hell or High Water, though indebted to the Western, is determined to turn one of Hollywood’s oldest genres inside out: There is no glamor nor is there glorification of violence. The West isn’t depicted as a land of opportunity; it’s a land that is dying, its vitality leeched by the parasitic banks; a land in which poverty is a hard hole to climb out of and can keep generations of a family trapped; where breaking out is almost impossible and, for the women, the only job prospects are waitress or bank teller. Unlike the John Ford Western, there is no heroic character played by John Wayne; the closest Hell or High Water has is Marcus Hamilton, and even then, he doesn’t get the showdown or satisfaction he wants except maybe on the script’s final ambiguous note.

Hell or High Water is part of an informal trilogy of scripts that Sheridan wrote at the beginning of his writing career (the other two being Sicario and Wind River), a trilogy about the “modern frontier.” In interviews, he claims he got the idea when he visited Archer City, hometown of Texan author Larry McMurty (The Last Picture Show and Terms of Endearment), and thought somebody ought to “rob the place blind” when he saw its state. I suspect it also stems from his own fantasies when, as a child, he saw his childhood home disappear and almost lost the family farm. Sheridan understands how the Great Recession affects the small towns hard; he is sympathetic to their plight.

Still, I’m not sure I enjoyed this script as much as I did Sicario or his other work. It’s gripping but I wonder if the script could have benefited from a few more, or maybe less scenes. It’s hard to say. Still, this script (which earned Sheridan his only Oscar nomination at the time of writing) offers a good template on how to write an unconventional screenplay: Less exposition, simple plot, more character. That’s the Sheridan formula, and it is working well in his favor, proving that there is an appetite for original stories in cinema.

Who is Taylor Sheridan?

Taylor Sheridan (born Sheridan Taylor Gibler Jr. on July 17, 1969) is an American filmmaker and actor. He started out as an actor with guest roles on popular TV shows like CSI, Veronica Mars, and Sons of Anarchy, but he struggled to turn into a sustainable way of living. He wrote his first screenplay in 2011, the pilot for what would become The Mayor of Kingstown, but even though it opened doors, Sheridan was reluctant to sell it unless he could make it. His breakthrough came in 2015 when Sicario released to critical acclaim, followed by Hell or High Water and Wind River. Even though he began writing and directing past the age of 40, Sheridan has achieved enormous stature especially thanks to the blockbuster success of the Yellowstone franchise and its various spin-offs. In a decade, Taylor Sheridan has become one of the biggest creative voices working in Hollywood, and so prolific that it makes you wonder when he finds the time to sleep (on top of everything, he runs a ranch!).

When asked at what point he decided to transition into writing, Sheridan famously quipped: “If you’re banging your head against the wall for 20 years trying to be an actor, maybe you shouldn’t be an actor.”

Knowing your limits, and moving on to find new talents, is an astute approach to finding success in a creative industry.

Notes:

Thompson, Anne (January 19, 2017) | How ‘Hell or High Water’ Oscar-Nominated Writer Taylor Sheridan Turned Failure Into Art: Awards Spotlight (Indiewire)