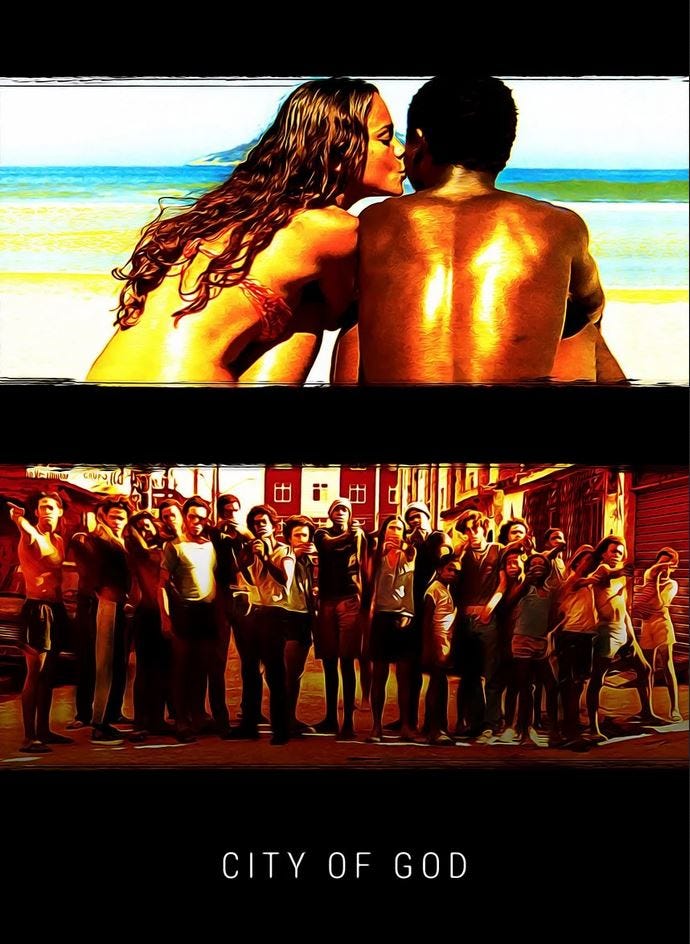

City of God (2002) Script Review | #70 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

City of God blends crime, ambition, and violence in a semi-autobiographical tale that evokes the energy and style of Goodfellas.

Logline: In the slums of Rio, the paths of two children diverge drastically as one struggles to become a photographer while the other rises to become a notorious kingpin of crime.

Written by: Bráulio Mantovani

Based on: City of God by Paulo Lins

Pages: N/A

SCRIPT UNAVAILABLE

One of the handful on non-English entries on this list and one without an available screenplay, City of God is one of the rare pictures that can claim to be the heir of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Despite different locales and settings, both stories are infused with a similar energy, rhythm, and style— right down to a voice-over giving context to the world we are about to enter. A script sadly does not exist because City of God was made with largely non-professional actors and rather than force them to memorize lines, the filmmakers created a space for them to act naturally (which adds authenticity).

What it does have is a robust structure, divided into three main vignettes (with the second one broken up into mini-vignettes), charting the lives of two boys growing up in the favela of Rio de Janeiro: Rocket and Li’l Zé, who aspire to escape the poverty they are mired in, except in very different ways. Rocket goes straight by working his way up to become a photographer though it is a long uphill struggle; Li’l Zé chooses the shorter but more volatile path by becoming the kingpin of the favela, a crown to which his sociopathic nature makes him well-suited for, even if for a while.

The story spans nearly two decades, from the 1960s to the 1980s (similar to Goodfellas, which covered the mid-50s to the early 80s), following the boys from childhood up to their teenage years. The first vignette, titled ‘The Story of the Tender Trio,’ keeps Rocket and Li’l Zé (then called Li’l Dice) largely on the sidelines to focus on three older hoodlums—Shaggy, Clipper, and Goose (Rocket’s brother). The second vignette, titled ‘The Story of Li’l Zé,’ jumps forward to track teenage Rocket embarking on his journey as a photographer, while Li’l Zé— aided by his easy-going and charming best friend, Benny— quickly takes over the drug trade in the favela. As Rocket wryly comments at one point: Had the business been legitimate, Li’l Zé would have been named Business Person of the Year.

This second vignette also has two smaller segments, ‘Sucker’s Life’ and ‘Flirting with Crime,’ which cover Rocket’s attempts to raise money to buy a camera, including a brief but failed stint to turn to crime. As the Second Act, this vignette is the longest of the three, and concludes with the tragic death of Benny.

The third vignette is titled ‘The Story of Knockout Ned,’ introducing a character who will become Li’l Zé’s nemesis and usher in the darkest part of the tale in which a war erupts between the kingpin and the citizen forced to fight him, and the ensuing fallout, from which Rocket is able to gain.

Like Goodfellas, the story is rife with violence but it is not the glamorized kind, nor judgemental. Just as violence is the code of the Mafia, the same applies in the favela. Violence and crime are seen as one of the few— if not only ways— to become prosperous, while an honest living is both difficult and financially not alluring. Being touched by violence becomes a stain that does not come off, as Lady Macbeth found when the damned spot would not go away. Knockout Ned, Li’l Zé’s enemy, is a peaceful bus conductor who sides with another gangster, Carrot (on account of his red hair), because Li’l Zé raped his girlfriend and then killed his brother and members of his family. Admittedly, the rape as a motivational device is… not great. But it does deepen the thematic underpinnings of masculinity and its perception in a poverty-stricken environment; one in which men pick up a gun to defend themselves and their loved ones, to tamp down the feeling of helplessness. Even Li’l Zé compensates for his insecurity by amassing power and killing people; the one rare time he shows vulnerability is when he shyly attempts to ask Ned’s girlfriend (he thought she was alone) to dance only to get turned down. For him, violence is the only way to get what he wants.

And then there’s Benny— who is accidentally killed instead of Li’l Zé, the real target, on the very night that he was leaving his life of crime with his girlfriend. Once the hand of violence touches you, it’s almost as if your fate is sealed. There’s something Shakesperean in all of this, especially in how it exploits its characters’ fatal flaws that dooms them. Ned is killed by the son of a bank security guard whom Ned accidentally shot in the early days of the war; Li’l Zé gives guns to the Runts (small children aspiring to be gangsters) to win them on to his side despite being antagonistic towards them; when Li’l Zé loses everything, the Runts kill him with the very weapons he gave them.

City of God is packed with memorable characters. Apart from the aforementioned names, there’s also— Stringy, Rocket’s best friend; Angelica, Rocket’s crush and then later Benny’s girlfriend; Blacky the dealer, and Thiago, to name a few. Each one with the own memorable personality that makes them stand out in the large cast.

It’s impossible to write a screenplay out of this kind of story; namely, it’d be impossible trying to capture the detail or realism found in the finished film. When shooting with non-professional actors, this is something to consider; reciting memorized dialogue might only generate stilted performances. In such instances, your best bet is to carefully plan out the sequence of scenes, identifying what should happen and the obstacles to be faced, and how each character should behave— and then ask the actors to perform the scene with this in mind.

City of God is an intelligent and entertaining story; inventive in its approach and novel in its subject matter; told with pizzazz and flair, and packed with unforgettable characters. They’ll still be talking about this one for another twenty years to come.

(Note: Ironically, on August 2024, a miniseries City of God: The Fight Rages On, picks up the story two decades after the film ends)