Children of Men (2006) Script Review | #18 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Prescient, haunting, and powerful, this timeless adaptation offers a bleak glimpse at a world fallen into chaos over fertility issues.

Logline: In a chaotic future in which women have become infertile, a former activist agrees to help transport a miraculously pregnant woman to a sanctuary at sea.

Written by: Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby

Based on: “The Children of Men” by P.D. James

Pages: 127

The Children of Men screenplay is not the final shooting script. But the bones of what would make the final cut and a substantial portion of the meat is here in this version; and it is gripping.

If one borrows a page from Blake Snyder’s seminal screenwriting book, Save the Cat!, this could be considered a ‘Dude with a Problem’ story, in which an ordinary man is thrust into an extraordinary situation and has to deal with it. The extraordinary situation in Children of Men is that in a world where a global fertility crisis in the near-future has brought about the collapse of social order, a young refugee in Britain is miraculously pregnant. The ordinary man, former activist Theo Farron, is unwittingly drawn into a murky conspiracy and does everything he can to get the girl and her unborn baby to a safe harbor.

How does Theo get roped into this business? Not by choice. His former lover (and mother of his dead child), Julian, reaches out and asks him to get a visa to help Kee, the young refugee, leave Britain. There are a few snags, though. First, Julian’s organization, the Fishes, have been designated as a terrorist group by a tyrannical British government. Second, Theo can only get a visa that requires him to travel with Kee. Third, there’s internal conflict within the Fishes over whether or not to use Kee’s baby as a political symbol against the government; that leads to Julian’s assassination, and the man who ordered the hit, Luke, to take over. When Theo discovers the truth, he goes on the run with Kee and Miriam, the midwife. Their destination: The Tomorrow, a ship that will shelter Kee. But their window to reach the ship is tight: they’ve got less than 48 hours to reach the last rendezvous point which is in Bexhill. The problem? Bexhill has been turned into a refugee camp. To get to Bexhill, they’ll have to get arrested.

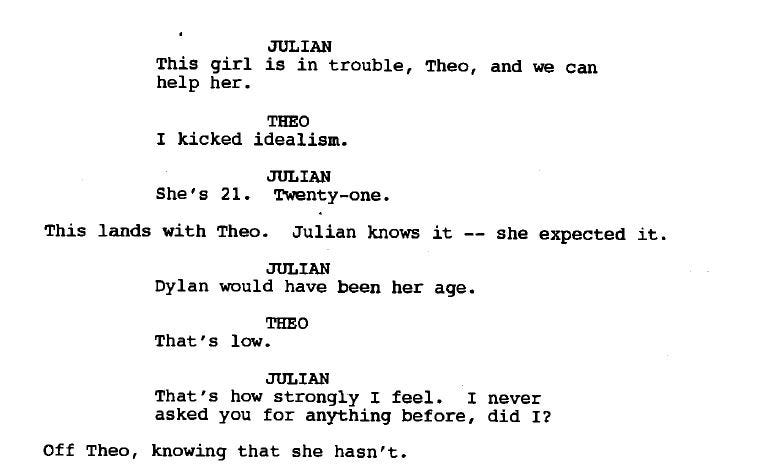

In Theo, we find a protagonist cast in the mould of ‘lost men who find a purpose,’ putting him in the company of the likes of Rick Blaine from Casablanca. His arc begins as jaded and cynical, and ends active and hopeful; in a way, protecting Kee helps Theo to rediscover himself. Although it’s omitted in the film, the script makes it explicit that one of the primary reasons that Theo aids Kee is because she is the same age that his son would have been if he had not died.

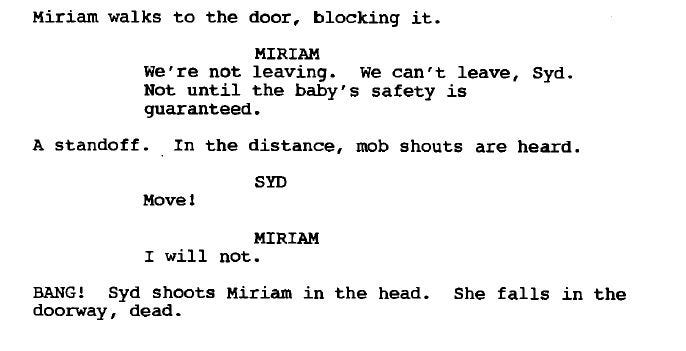

The script has two parts. In the first half, from page 1-53, Theo reluctantly tags along though he’s doing it only for the money; from page 54, Theo is prompted into action, partly out of survival, partly because Julian told Kee to trust him should anything go wrong. They go to Theo’s friend, Jasper, who has a contact that can get them into Bexhill. Tragically, Jasper is killed along the way; here, he is killed by a pack of wild dogs, while in the film, he is killed by Luke. Notably, though, in both instances, he dies to buy Theo, Kee, and Miriam time to escape. Around page 78, the trio are taken into Bexhill; another major difference in this version of the script is that Miriam survives to help deliver Kee’s baby; in the film, she is dragged off the bus, leaving only Theo to help Kee. In the script, Miriam is shot by Syd, Jasper’s contact.

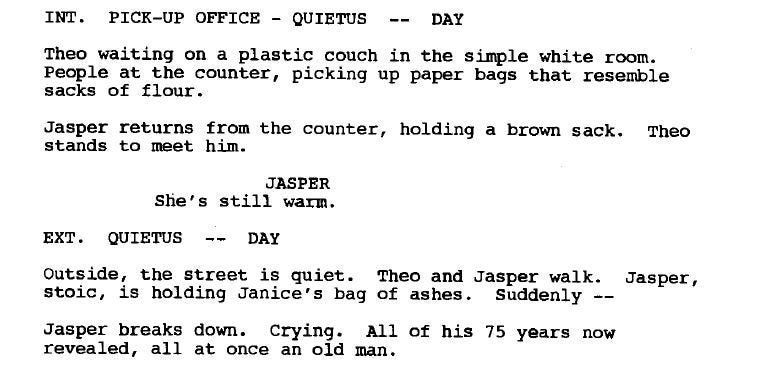

In terms of plot, the script’s framework is remarkably simple. In the setup, we learn that the youngest person on the planet has been killed and that there are no more children; we meet Theo and Jasper; and we learn what the future is like (read: not pretty). On page 13, Theo is kidnapped by the Fishes, is given a ‘call to adventure’ by Julian but Theo refuses. However, he changes his mind and goes to see his cousin in order to procure a visa but can only get a joint visa; he refuses again. But when Jasper’s wife, Janice, commits assisted suicide, Theo changes his mind (in the film, this scene does not happen; it’s implied that he agrees to go along with Kee for the money— in my opinion, the latter is more convincing).

Act 2 opens with Julian’s assassination, and Theo suddenly thrust into circumstances he didn’t sign up for. This leads to the reveal of Kee’s pregnancy and the real reason for the visa, along with Luke being appointed as the new leader of the Fishes, and the disclosure that he arranged for Julian’s death. Theo, Kee, and Miriam flee to Jasper’s. From there, they make their way to a contact point with Syd. Jasper is killed; the trio are smuggled into Bexhill. During this, Kee goes into labor but Miriam and Theo help deliver the baby.

But in Act 3, Bexhill comes under attack the next day. Syd kills Miriam, but a gypsy named Marichka helps to overpower Syd and take them to temporary shelter with some Georgians. They help Theo and Kee navigate increasingly volatile streets until they are caught by Fishes who recognized Theo and broke into Bexhill. A massive fight ensures between all sides, but Theo’s only concern is saving Kee from the Fishes and escaping to the rendezvous point with The Tomorrow. Alas, amid all the shooting, Theo is fatally injured and dies from blood loss, though not until he makes sure Kee is there to meet the ship.

A loose adaptation of the novel by P.D. James, Children of Men blends drama, action, and intrigue with political and social commentary. The future presented in this script (2024 in the script; 2027 in the film) is now, and it is frightening. The lack of children has torn apart the social fabric around the world. The Britain in the story resembles the grim country in the pages of the graphic novel, V for Vendetta. In such a world, what would happen if a woman got pregnant again? How would people react?

When Alfonso Cuarón first came across the book, neither he nor Timothy J. Sexton were convinced that the premise was little more than a glorified B-movie. But after the 9/11 attacks, Cuarón suddenly thought the fertility crisis was a good “metaphor” for a “fading sense of hope.” Still, he didn’t want to make a faithful adaptation of the book, which was more of a Christian theological view of the crisis; that certainly did not hold Cuarón’s interest. Except for an abridged version, he never read the novel because he did not want it to clash with what he had in mind! (Sexton did, though, and incorporated elements into the script). Instead, he read philosophers such as Slavoj Žižek and John Gray, as well as activist journalists like Naomi Klein; he wanted to steer away from dystopia and root it in real-world issues. The two writers traveled to New York after the travel ban was lifted; during this time, they also got a front-row view to anti-globalization protests in Milan. All this contributed to their vision, and in London, they completed an early first draft.

But around the same time, Cuarón halted work on the script to direct the third instalment of the Harry Potter franchise, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. This proved crucial as it allowed him to experience the social dynamics of the British psyche at the time, after which he added the immigration angle to the script. However, the script nearly got derailed when three other writers were brought on board by the studio to work on it; David Arata and writing duo Mark Fergus and Hawk Ostby received credit due to issues with the Writers Guild, but Cuarón claims he never met them. From cryptic hints in interviews, it appears that they were brought to turn it into a “generic action movie.” If anything, Cuarón credits actor Clive Owens as the other writer who contributed the most to the screenplay, bringing his instincts and ideas to the material as the three locked themselves in a hotel room and fleshed out the Theo character. My guess is that this draft was before Owens signed on; it lacks the little nuances and moments that made the film so great. For instance, the script has Theo reacting angrily when meeting Julian after so many years; in the film, Owens decided to play it muted. A more effective decision, in my opinion.

For Cuarón, Children of Men has two main characters: Theo, and the environment. This, he believes, is what prevents it from becoming a “generic chase movie.” He wanted to weave in social environment commentary about the state of things; he brought the art department photos from Sri Lanka, Iraq, Northern Ireland, and Somalia for reference, no doubt influencing the story deeper. One can consider this instead as a “road movie in which a reluctant hero tries to bring a character to safety.” Reminds me a lot of Mad Max: Fury Road (#68 on the WGA 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century).

The writing is great. I especially I love the way the script plunges us immediately into the world with a TV report announcing the death of the world’s youngest person. It automatically creates a sense of mystery—why is the world stunned? Why is this the world’s youngest person, and what does it mean?

There’s also rich character description, it brings images to vivid life using a variety of techniques such as onomatopoeia…

While some readers might bristle at the liberties taken with adapting a novel, one person who loved the changes and endorsed the adaptation was P.D. James herself. She seems to have understood that the story wouldn’t completely work in the medium of film; the script itself uses the source material as a launching pad to tell a similar story, but differently. It takes a somewhat sci-fi premise and uses it to explore how characters would navigate such a world (note that it never goes into the specifics of what caused the fertility crisis). Nothing here feels dated; if anything, it feels timelier than ever. Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, Children of Men shows how hope can be found in such bleak situations, and slyly asks whether we have learnt anything at all from this. Looking at the state of the world, it’s safe to say that Children of Men was ahead of the curve.

Notes:

Guerrasio, Jason (December 22, 2006) | A New Humanity (Filmmaker Magazine)

Rahner, Mark (December 22, 2006) | Alfonso Cuarón, director of "Y tu mamá también" searches for hope in "Children of Men" (The Seattle Times)

Szymanski, Mike (December 15, 2008) | Director Alfonso Cuarón and the cast of Children of Men discuss politics, the future and Michael Caine's flatulence (Sci Fi Weekly)

Douglas, Edward (December 8, 2006) | Exclusive: Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón (ComingSoon)

Cuarón, Alfonso (September 21, 2006) | ‘Children of Men’ Feature (Time Out)

Interview: Alfonso Cuarón (Movie Hole)

Voynar, Kim (December 25, 2006) | Interview: Children of Men Director Alfonso Cuarón (Movie Fone)

Suton, Koraljka | The Future is Now: Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Children of Men’ Paints a Bleak Picture of a World Devoid of Humanity (Cinephilia Beyond)

Riesman, Abraham (December 26, 2016) | Future Shock (Vulture)

Perry, Kevin E.G. (December 24, 2021) | Children of Men at 15: ‘London in winter is a good place to imagine the end of the world’ (The Independent)