Brokeback Mountain (2005) Script Review | #13 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

This is not a tragic romance, but a haunting indictment of homophobia and how it prevents two people from spending their lives together.

Logline: Two modern-day cowboys meet on a shepherding job in 1963 and develop a sexual and emotional relationship, which becomes complicated when both get married to their respective girlfriends.

Written by: Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana

Based on: The short story “Brokeback Mountain” by Annie Proulx

Pages: 99

Scenes: 162

Brokeback Mountain is a painful story about homophobia, all the insidious ways it forces two men to keep their deep and abiding love for each other a secret, as prejudice and social dictums thwart a rare connection between two souls. In 99 pages and across 20 years, we live with them, witness them at their best, worst, and loneliest moments, rejoice and grieve at their trials and tribulations.

It begins in 1963, and it ends some time around 1983. Two poor modern-day cowboys arrive in Signal, Wyoming, to take up a shepherd job. One is Ennis Del Mar, a man of few words and even less money. The other is Jack Twist, a little more extroverted and with his own pickup truck. The two are assigned to wrangle sheep at campsites in Brokeback Mountain for a few months. As Ennis and Jack get to know each other, that summer in the mountains will turn into a brief but eternal memory for the young men, as they fall in love and then part ways.

The summer at Brokeback Mountain takes up Act 1, allowing us to spend time with the two cowboys and get to know them. Act 2 will offer parallel storylines, as Ennis marries a sweet woman named Alma, who loves him, gives him two children; though unsurprisingly (to us), she doesn’t enjoy the sex she has with Ennis.

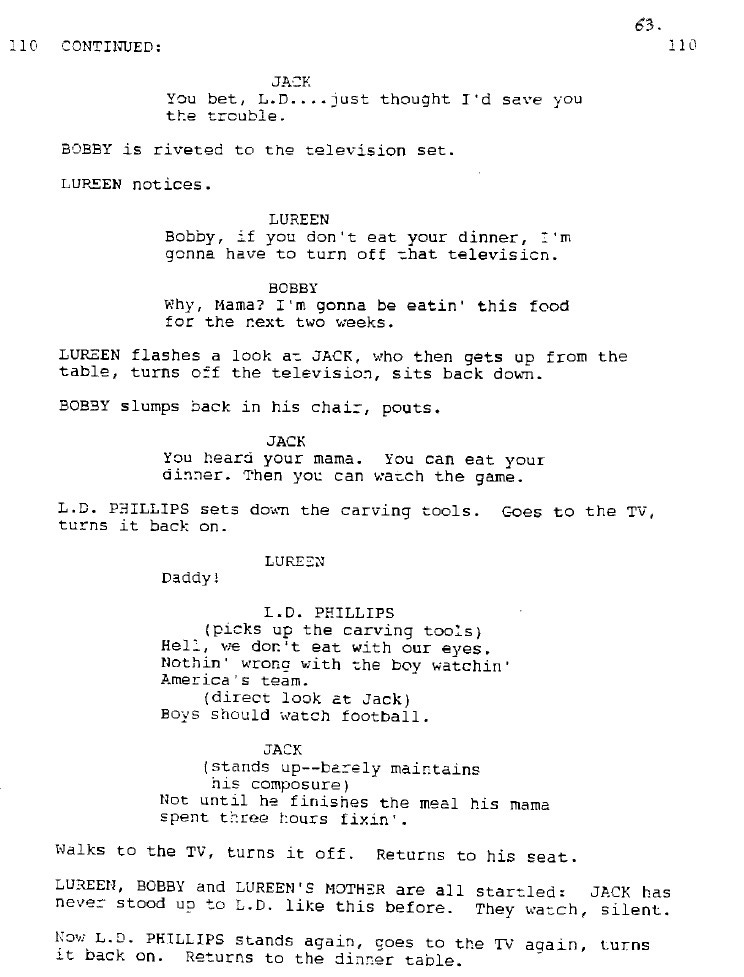

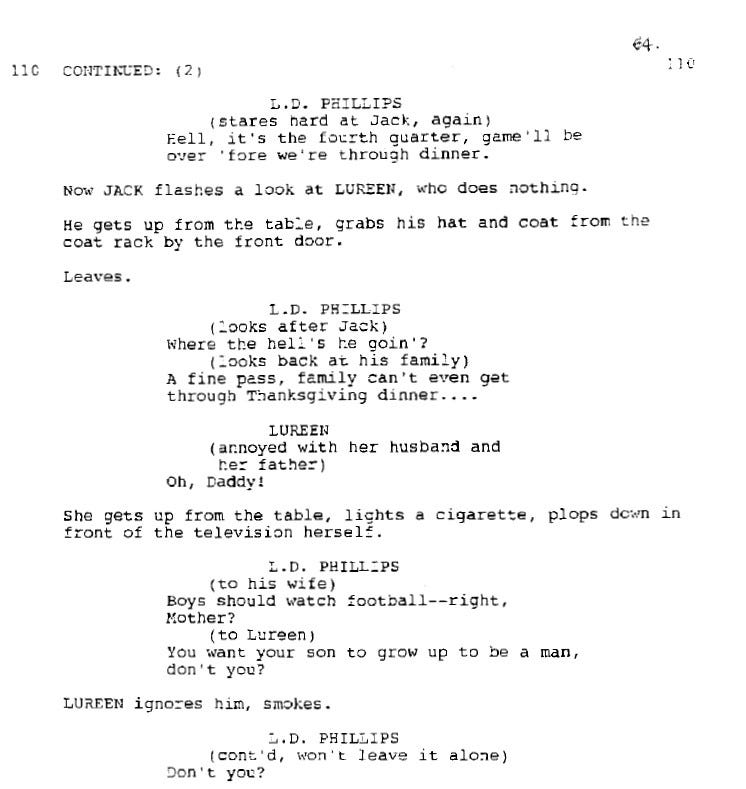

When the marriage inevitably fails, Ennis’ life slowly declines while Alma remarries. Jack doesn’t fare much better at first, either. Success eludes him; so do his attempts to pick up other men. But unlike Ennis, Jack marries the wealthy Lureen Phillips, even though his heart belongs with Ennis. Worst of all, for him, he has to contend with her alpha-status father, L.D. Phillips, best illustrated in a tense Thanksgiving dinner where the two men have a stand-off in Scene 110.

In fact, after their parting on page 32, Ennis and Jack don’t reunite until the Midpoint on page 48. Alas, it spells disaster for Ennis when Alma spies them kissing, setting in motion the beginning of the end of their relationship. Unlike Alma, we don’t get many scenes with Lureen to gauge whether she knows or suspects Jack’s true sexuality; but we can imagine the toll it takes on her life, just as it does on Alma, and the children, and how it stunts them. Ennis. Jack. Alma. Lureen. Later, Cassie. All of them, directly and indirectly, are victims of homophobia. For Ennis and Jack, the only time they can get to be with each other are a few days every year, pretending to be on fishing or riding trips to excuse their absence. A handful of moments for a lifetime. Jack is prepared to give it all up to build a life with Ennis; note how the first time he hopes this, it gets cruelly dashed in Scene 105.

Why is Ennis reluctant, though, to take the chance? For starters, he has his children. As much as he wants to be with Jack, he loves his daughters too much to be apart from them. But more than that, he has a fear of being killed after a childhood memory of being shown the corpse of a man who was beaten to death for suspected homosexuality.

After the divorce, Ennis ends up in a relationship with a waitress, Cassie Cartwright, but how long can it last before it ends too badly?

Act 3 slowly moves towards its inevitable tragedy. Jack dies, unseen, in an accident but hints are dropped and suggestions made that he was actually killed by his father. Ennis is devastated, especially when he discovers that Jack had kept one of his shirts from that first summer on Brokeback Mountain. His relationship with Cassie ends; he is left alone.

Some might accuse Brokeback Mountain of succumbing to the cliché of having queer characters face an unhappy ending; had this been a romance story, I’d agree. But Brokeback Mountain isn’t a romance; it never was. Annie Proulx, who wrote the short story on which the script is based on, meant it to be a devastating tale about how homophobia imprisons people, keeps them trapped, especially in the American West in which it can lead to violent ends. Ennis sacrificed a chance at happiness, and sacrificed Jack’s too. Ennis might still be alive, but was it worth the price?

The journey from short story to screenplay and ultimately big screen took nearly a decade to see the end. Screenwriter Diana Ossana first came across Proulx’s short story in The New Yorker in 1997. The next day, she forced her writing partner, Larry McMurtry, to read it. McMurtry was reluctant at first, having an aversion to short fiction. But halfway through, he recognized that he was reading a masterpiece. The duo wrote a “fan letter” to Proulx in the hopes of getting permission to adapt it as a feature. A week later, they received a reply: they had her blessing, though she was at a complete loss as to how it could be done.

McMurtry and Ossana were less daunted. McMurtry had already made a name writing novels such as Terms of Endearment and The Last Picture Show (which he co-wrote the screenplay for), and knew a few things about the Old West and crafting powerful stories. Ossana had worked with McMurtry since 1992, and was instrumental as a writing partner. Together, they lifted the skeleton of the short story and used that as the bones of the screenplay. But the length of the short story forced the duo to come up with two-thirds of the material from scratch. Ossana wondered how Ennis and Jack’s wives felt about being in a marriage with closeted men; she saw the ripple effect it had on the people connected to the cowboys. That formed a substantial portion of the screenplay, and added to its tragic dimensions. Both McMurtry and Ossana understood the importance of retaining the language of the characters, the need to avoid veering into sentimentality, and the desire to subvert the American Western.

On all three fronts, they’ve succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The script packs the power of a shotgun blast. The writing has a poetic quality that moves you deeply, even taking great pains to help us envision the characters. Look, for instance, at how Jack and Ennis are introduced; yes, it takes paragraphs, but they convey everything we need to know about them, as well as offer something for the actors to work on.

The writers also manage to capture the voices of all the characters with startling precision; you can practically hear the accents and cadence when they speak.

Since Ennis is not much of a talker, many scenes have to convey his mood and state of mind in actions— it does a remarkable job in showing us how he is feeling.

The same applies to Alma, especially the scene in which she discovers Ennis’ homosexuality.

Pulling this off required McMurtry and Ossana to know the characters intimately so that every word they spoke, every action they made, rang true to their personality, by a process of envisioning them vividly as they wrote. Their writing process was a true collaboration— Ossana would start the draft, writing up 20-30 pages before sharing them with McMurtry, after which they would discuss and make changes before he wrote, and so on until the first draft was complete.

This is not the final screenplay. Some scenes, such as Ennis having to contend with Alma after he goes away to a motel room with Ennis, are missing. Lureen, mentioned here as Phillips, is changed to Newsome. Still, the script is more or less close to the final version.

For their efforts, McMurtry and Ossana would win a slew of trophies, including the Academy Award, BAFTA Award, Golden Globe Award, and Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Richly deserved, too. Here is a screenplay that unfolds with care, never in a hurry to get to the next scene, yet making it impossible to not keep turning the page. It luxuriates in the unspoken, hums powerfully in the exchanges uttered. Like Ennis and Jack, we have been to Brokeback Mountain and back. We keep their story with us, and we hope that in another time, perhaps theirs would have a happier ending.

Notes:

Simpson, Michael Lee (June 9, 2021) | Diana Ossana, Oscar-Winning Screenwriter, Reflects On “Brokeback Mountain” (Creative Screenwriting)

Strachan, Maxwell (December 9, 2015) | 'Brokeback Mountain,' 10 Years On (Huffington Post)

Miyamoto, Ken (July 25, 2016) | ScreenCraft Exclusive: One-On-One with "Brokeback Mountain" Screenwriter Diana Ossana (ScreenCraft)

(, 200) | (Cinemalogue) https://cinemalogue.com/2006/02/14/brokeback-interview/