Bridesmaids (2011) Script Review | #12 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A heartfelt and bawdy comedy that proves the girls can be just as funny as the boys.

Logline: When Annie’s best friend, Lillian, gets engaged, she soon finds that her position as the maid of honor and her friendship with Lillian threatened by newcomer, Helen. As the wedding day approaches and the competition escalates, Annie shows just how far she’ll go for the people she loves.

Written by: Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig

Pages: 109

Scenes: 135 (estimated)

The Bridesmaids screenplay is a unicorn: a rare, gut-bustingly funny, and sincere comedy that proves women be as raunchy and hilarious as the boys. It reads like a breeze; clever, sad, and mortifying on multiple levels, packed with laughs from start to end.

Annie Walker is in a weird place in her life. She works in a jewelry store after her bakery closed down; she lives with two weird British siblings; and she’s in a friends-with-benefits (FWB) situation with Ted, a guy who clearly does not value her as much as she does him. The only bright spot is childhood best friend, Lillian Donovan. But even that may not last for long: when Lillian gets engaged, Annie suddenly has to contend with the possibility of losing her friendship to the stress of marriage. As if all that wasn’t enough, Annie has to also contend with Helen Harris III— the trophy wife of Lillian’s fiancé’s boss. Gorgeous, rich, and seemingly having everything together, Helen seems determined to upstage Annie as the maid of honor and even replace her as Lillian’s new best friend, sparking off an intense rivalry.

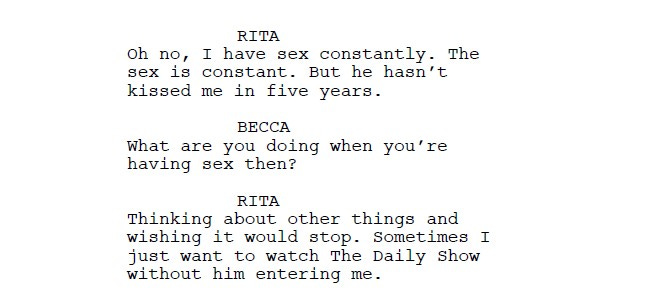

Of course, the title is Bridesmaids—as in, plural. The rest of Lillian’s crew includes Rita (Lillian’s cousin), Becca (Lillian’s newly married colleague), and Megan (Lillian’s soon-to-be sister-in-law). They’re not there merely for ornamental purposes— together with Annie and Helen, each woman represents different stages of what married or single life is like. For instance, Megan is the opposite of Annie— although single, she is sexually uninhibited, happier, and successful (a government job with high security clearance, and she knows where all the nukes are—and their codes!); basically, if Annie is barely holding it together, Megan has it together. Becca, still in the honeymoon phase of her marriage, has never been with anyone else except her husband and it turns out her sex life isn’t too great; Rita, the only mother in the group, is trapped in a joyless marriage; and Helen, too, is lonely in both her marriage and her life, without any friends. I got to be honest, after writing all that, this sounds like a real horror story.

In addition to the shenanigans that the bridal party gets up to and Annie and Lillian’s friendship, the script also adds a rom-com layer to the proceedings. Being single, she keeps going back to Ted for sex and feels bad about it, yet can’t help it. (We also learn that when the bakery closed down, her boyfriend at the time broke up with her. Basically, Annie hasn’t had the best luck with men). But along enters genial Irish cop, Officer Rhodes, in a meet-cute where he flags her down for a broken taillight. He’s smitten; she’s ambivalent. Can these two make it work?

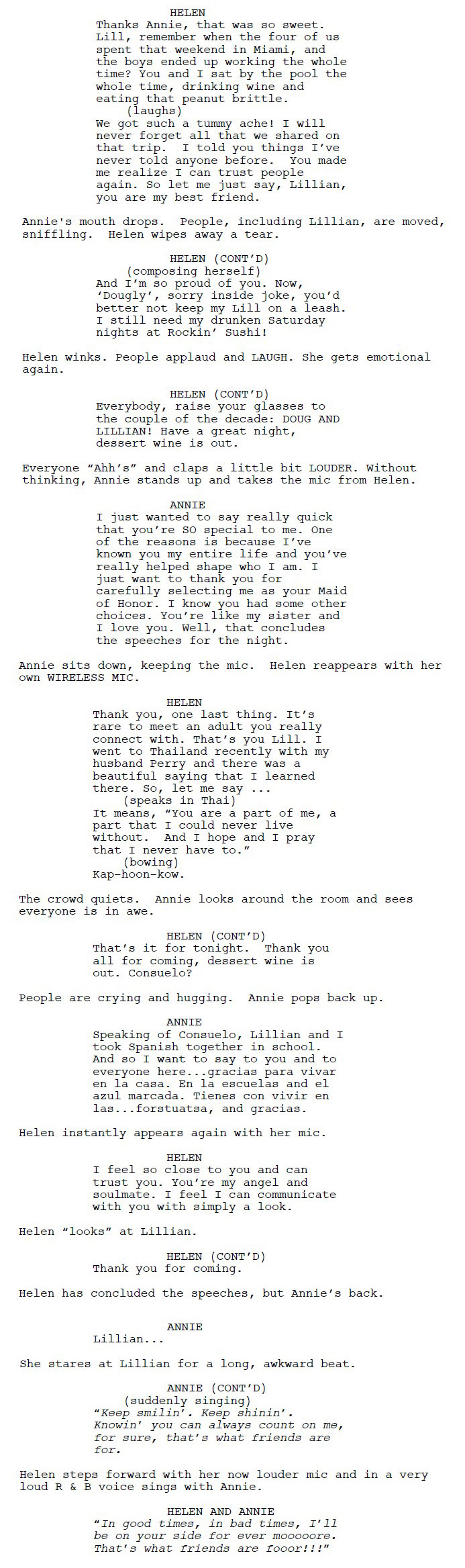

Writing comedy is harder than most other genres, not just because humor is subjective, but because it requires a lot of variety to keep the comedy alive until the credits roll. Bridesmaids has different types of comedy. There are the scenes that rely on cringe such as when Annie and Helen try to one-up the other at Lillian’s engagement party…

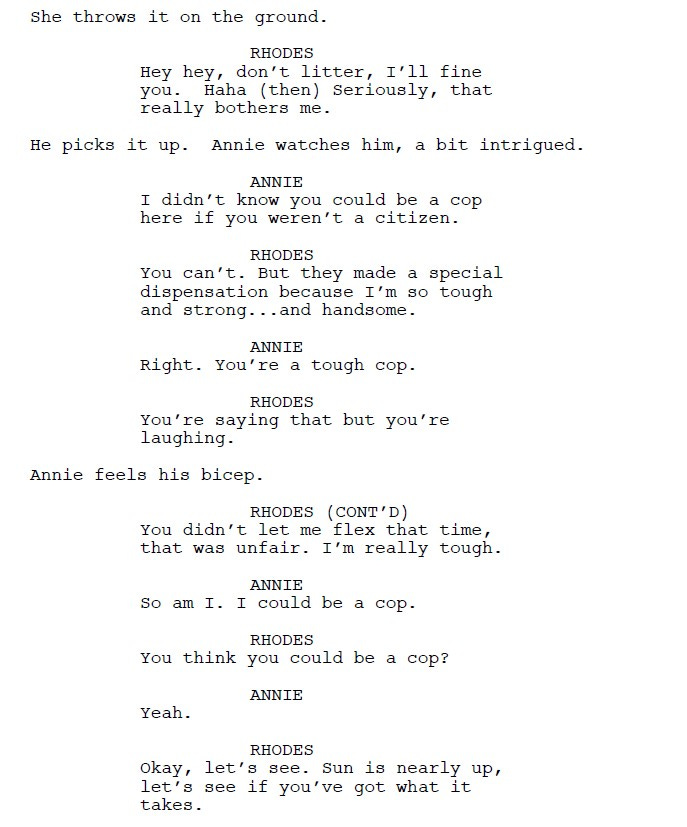

There’s the banter between Annie and Rhodes that rely on clever turns of phrases…

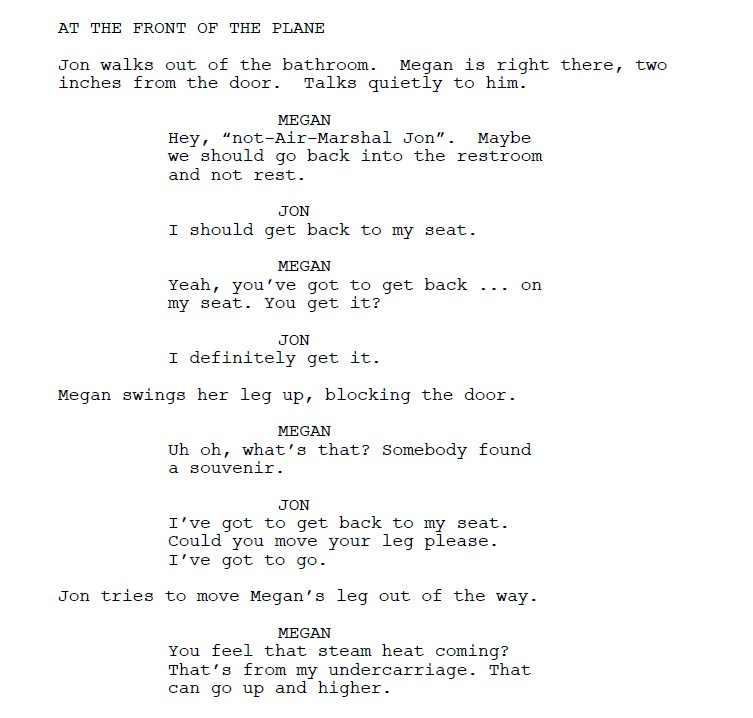

There’s the outrageous stuff that characters like Megan says…

There’s the revelation of bitter truths about marriage that are couched in humor…

And of course, there are the gags, such as the memorable scatological scene between page 39-45, that is funny not because women suffer food poisoning at a fancy place but because Annie refuses to admit to Helen that the cause of the food poisoning was the Brazilian restaurant that she took them to.

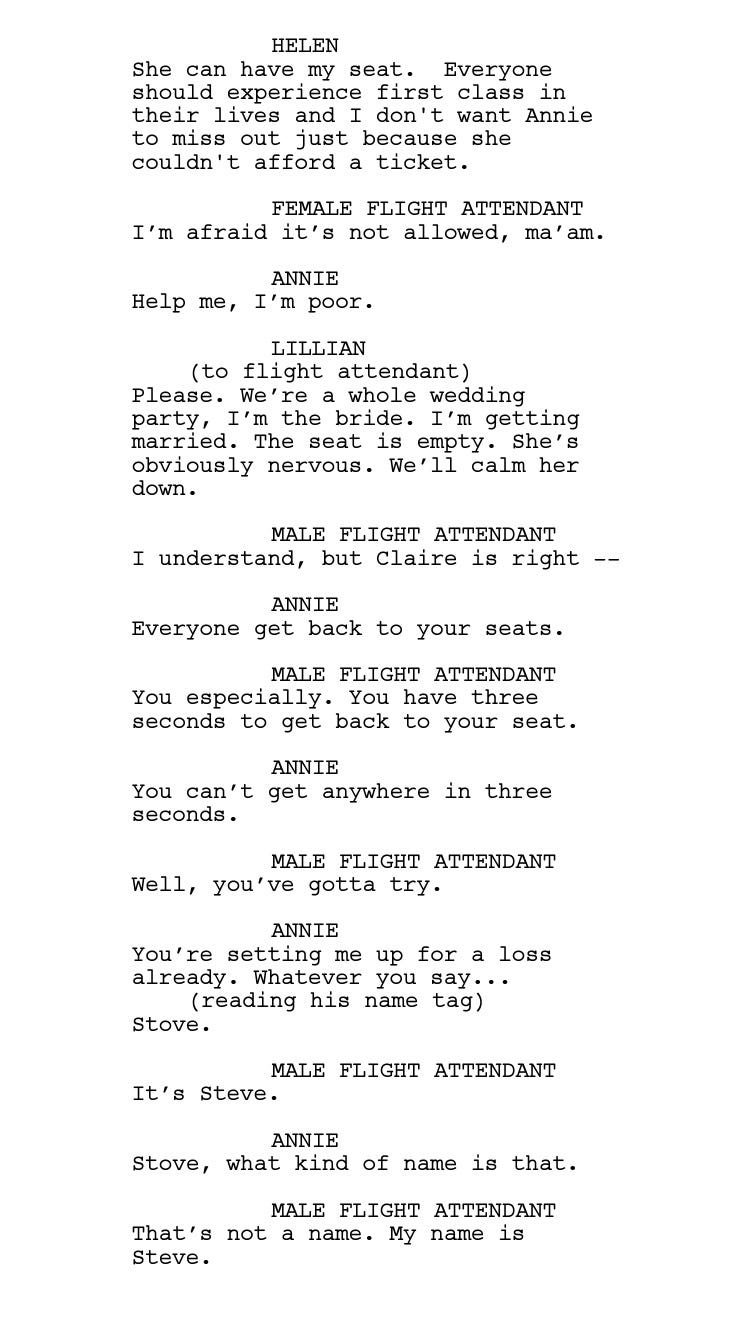

Although I would say that the moments in the aborted trip to Vegas for a bachelorette party comes close to topping it, especially what might be my favorite exchange between a drugged-out Annie and a flight attendant.

But none of this would work for too long unless the script got us invested in the characters. We feel for Annie because when the story opens, she’s at a low point in her life. From there, it keeps sliding down until it picks up by the end. We can relate to Annie’s predicament— who hasn’t dealt with a situation where we think someone else is encroaching the territory that we have with our best friend? But she’s also a flawed character, unaware that she has the power to hurt people; like Rhodes, as demonstrated in the scene when she abruptly leaves his house after they spend the night together, because he tried to encourage her to start baking again.

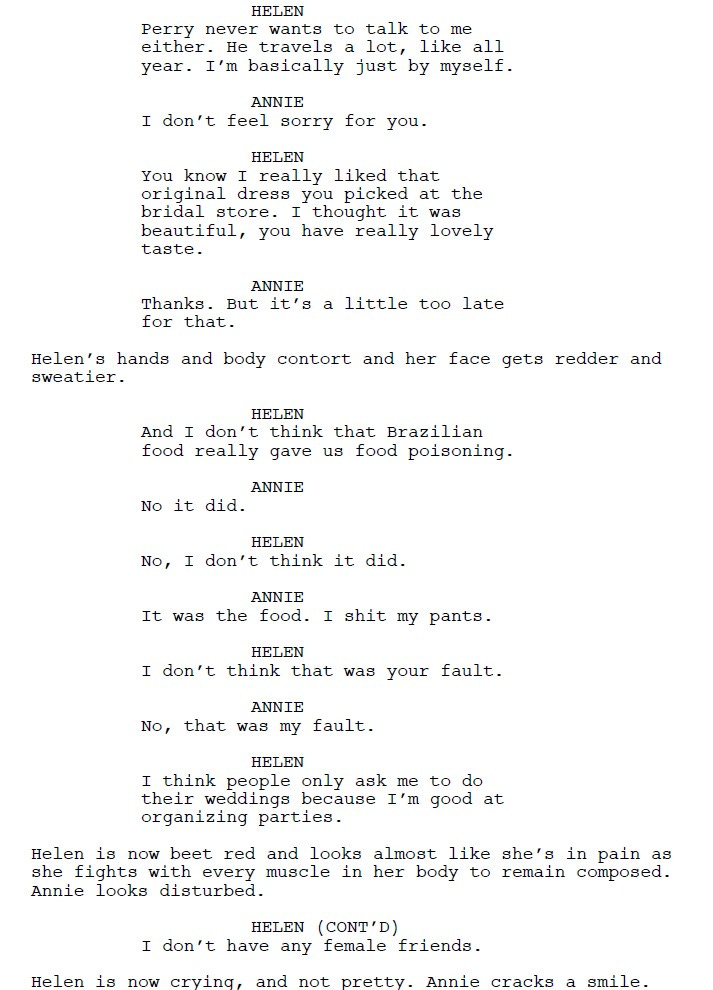

Even Helen, though set up as the antagonist, is not a one-note villain. Yes, she’s primed to make you hate her because Annie hates her. But there are two scenes—one early on, another closer to the end—that hint at her deeply lonely situation.

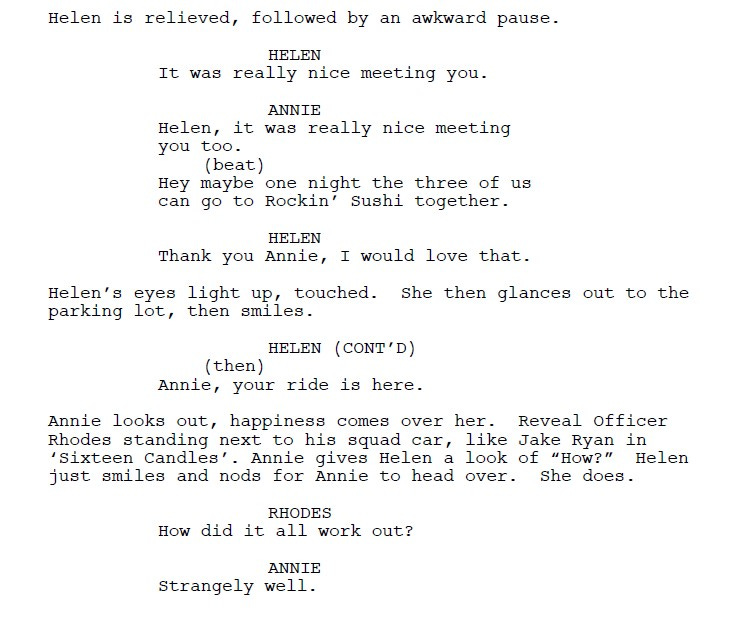

Moreover, it is her little intervention that helps Rhodes and Annie get back together, allowing Annie and Helen to put aside their antagonism and find a space for friendship.

And that’s the secret to writing comedy that outlasts its jokes: it’s the characters and story that holds it all together. If you scrapped the jokes and the gags, Bridesmaids could still function as a drama.

One of the many marvelous attributes of this screenplay is the brevity in the writing. Using few words, the writers are able to conjure sharp and vivid images, blending camera and edit directions in its descriptions to get the point across.

Although in a scene such as when Annie tries to get Rhodes’ attention when he’s ignoring her, it doesn’t hesitate to get into detail in the paragraphs.

If needed, it references other movies to indicate what it expects out of a scene, such as using The Color of Money for staging the tennis game between Annie and Helen.

It also aims to end several scenes on a punchline so that the comedy carries throughout the story.

The origins of Bridesmaids date as far back as early 2006. After Kristen Wiig had a small role in Knocked Up, Judd Apatow asked her if she had any ideas for a screenplay for her to star in the leading role— he did the same thing a few years prior with Steve Carrell that led to The 40-Year-Old Virgin (#94 on the WGA List of 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century). Wiig enlisted her friend, Annie Mumolo, to help her and the two worked on the script over the next couple of years (at the time, Mumolo was in Los Angeles while Wiig was in New York working on Saturday Night Live). They’d meet on weekends to share notes and ideas, before conducting ‘table reads’ of drafts with Apatow for feedback. Despite putting together a first draft in a record six days (!), it was only after years of rewriting and tweaks that the story hit its true potential. One of the reasons it took a while was because the initial attempts tended to resemble a series of comedy sketches stitched together instead of being a screenplay. But once Mumolo and Wiig reached a point where the material was good enough to get a greenlight, the duo picked a ‘How to write a screenplay’ book and began to tighten the screws on the script.

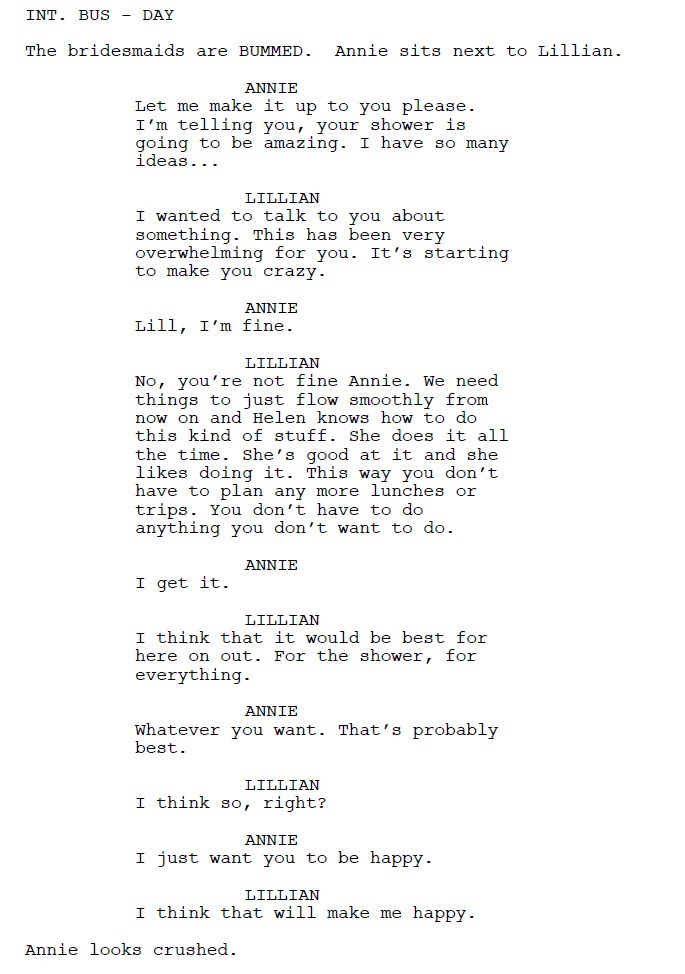

For instance, the Ted character was originally split into three variations of a bad date, before being combined into one character. Another was turning passive actions and choices into active ones. For example: In an early draft, Helen took over Maid of Honor duties directly after the plane fiasco, whereas in the final version, it is Lillian who makes the choice to relieve Annie from her duties, thereby widening the rift between the friends.

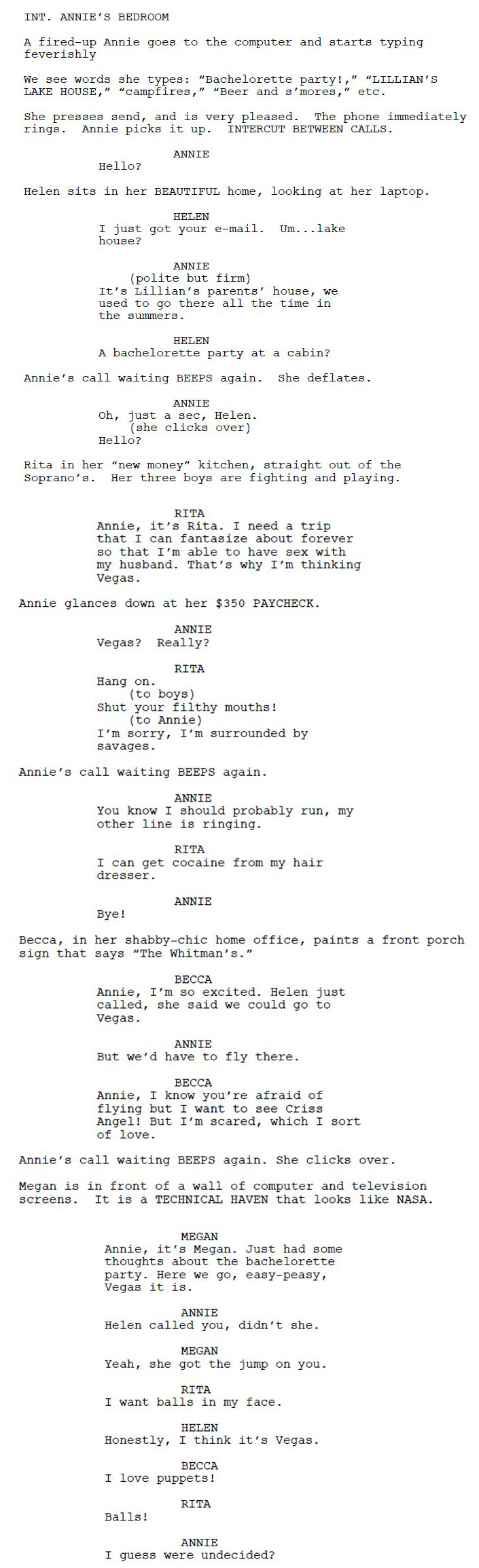

Another choice they made was to change a number of phone call conversations in the script into in-person conversations, including Annie and Lillian’s first scene together. Phone conversations tend not to be very cinematic and can lose the audience if not done right. Not that Mumolo and Wiig removed all the phone conversations—there is one between Annie and the other bridesmaids discussing the bachelorette party, but the way it’s staged and written only enhances the comedy, and makes it worth keeping.

Mumolo and Wiig’s first feature screenplay landed them a rare Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (it’s never often when they recognize comedies in this category), as well as the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay. Try to name another R-rated comedy, much less a female-led R-rated comedy (or any comedy, for that matter), to achieve such a distinction. But Bridesmaids is not on this list because it has a predominantly female cast of characters or because it’s raunchy. It is on this list because it is a wonderful story about keeping our childhood friendships as we grow up and grow older. It just happens to have a predominantly female cast of characters and happens to be raunchy.

Notes:

Lee, Chris (December 13, 2011) | Could Judd Apatow and Kristen Wiig's ‘Bridesmaids’ Nab an Oscar? (The Daily Beast)

Hughes, Sarah Anne (May 13, 2011) | Kristen Wiig reveals how she co-wrote ‘Bridesmaids’ screenplay (The Washington Post)

D’Costa, H.R. | Screenplay vs Film: 12 Screenwriting Tips from Bridesmaids (Scribe Meets World)

Milly, Jenna (May 10, 2011) | Podcast: Screenwriter Annie Mumolo Talks BRIDESMAIDS (Script Magazine)

Keegan, Rebecca (May 8, 2011) | Kristen Wiig, so weird on 'SNL,' goes (somewhat) normal for 'Bridesmaids' (LA Times)