Almost Famous (2000) Script Review | #9 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

Cameron Crowe's semi-autobiographical script is a coming-of-age tale and a love-letter to rock-and-roll all wrapped in one.

Logline: In 1973, 15-year-old William Miller’s love of music and aspiration to become a journalist lands him an unlikely assignment from Rolling Stone magazine to interview and tour with up-and-coming band, Stillwater.

Written by: Cameron Crowe

Pages: 165

Through the semi-autobiographical Almost Famous screenplay, Cameron Crowe turns his experiences and memories as a teenage reporter working for Rolling Stone magazine into a tender and sincere drama that is both a coming-of-age tale as well as a love letter to the last age of innocence for rock-and-roll music. It will leave you floored.

1975. Young William Miller, a fifteen-year-old prodigy, lands himself an assignment to tour with and interview the up-and-coming band, Stillwater— and then return home in time to sit for his school exams. But William doesn’t realize that getting musicians to give him the time of day is near-impossible, not to mention having to navigate their fraught insecurities and egos. As a reporter, he has to maintain objectivity without getting caught up in the band’s halo of charisma. If that wasn’t hard enough, he’s got a hard crush on Penny Lane, a Band-Aid (not a groupie!) who accompanies Stillwater on their tour; or more accurately, accompanies guitar player Russell Hammond, who seems destined to outshine the rest of the band. A lot happens in this script. It’s deeply personal in a way that only an insider of this world could know.

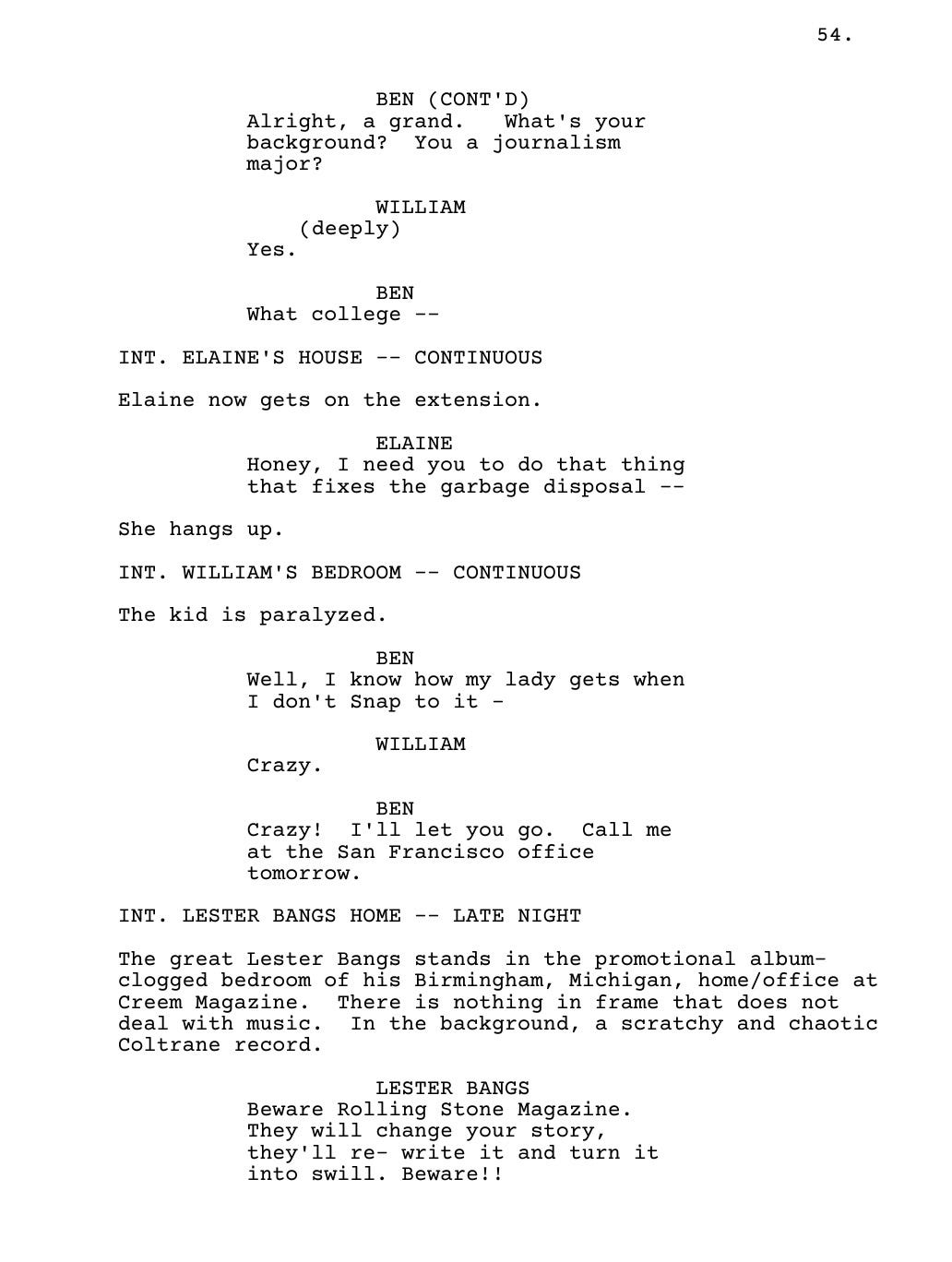

That’s perhaps why it also eschews a lot of the conventions of screenwriting. For instance, the assignment from Rolling Stone, which would be the inciting incident, doesn’t occur until page 54!

What precedes it, instead, is almost pure setup that introduces us to William’s life, rather strict mother Elaine (who lied to him about his age), and his free-spirited sister, Anita; it also introduces us to Lester Bangs (a fictionalized version of the music journalist), as well as Stillwater, Penny Lane, and her friends, Estrella, and Pollexia. Most scripts would be halfway through the narrative by this point; in Almost Famous, the fun is just getting started.

The title, Almost Famous, is both a literal allusion to Stillwater’s tour— called ‘Almost Famous’—and a figurative allusion to those who are on the fringes of celebrity, yet never quite make it. Although Crowe focuses on his teenage protagonist, he devotes an equal portion of time to the on-again off-again relationship between Russell and Penny Lane, and this might be the weaker part of the script. For understandable reasons, Crowe sands down the more scandalous elements of the time and keeps it cleaner; this despite a scene in which young William loses his virginity in a threesome despite being underage. I really don’t mean to be a prude, and I’m sure William consented to it, but… it feels more off-putting to read than what he certainly intended.

It also does a disservice to the character of Penny Lane. Originally introduced as a fiercely free-thinking woman, she nearly kills herself on an overdose of barbiturates because Russell trades her for $50 and a pack of Heineken in a game of poker and chooses to be with photographer, Leslie. It might be the weakest part of the story that actually mars everything else it has going for it. And that’s a shame. The other characters have dimensions to them—Russell is the only one who treats William seriously; Elaine’s overprotective nature and eccentric thinking comes from a place of good intention. Even Penny Lane, up until the last third of the script, is drawn in multiple shades— she’s warm and kind, especially to William, but seems to not see (or chooses not to see) that she deserves better than Russell.

Almost Famous could not have been made as a feature today; it is not at all commercially prospective, and actually underwhelmed at the box-office on release. It would find a home as a limited series on television, but I don’t know if that would have worked out in its favor. The story that Crowe has written works as a feature film even though it doesn’t feel like a traditional feature film. The intimacy it creates is akin to hearing a friend or an older parent tell you about what they got up to as a teenager. If, you know, a friend or older parent worked on music magazines interviewing music bands.

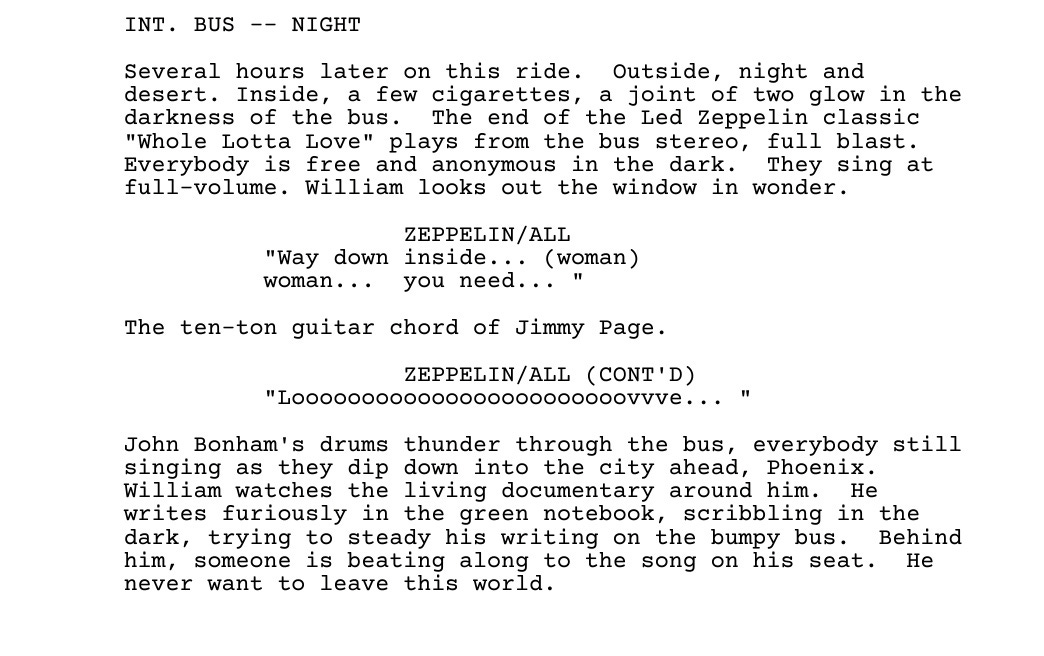

Stillwater is a composite of real bands with whom Crowe went on tour— The Allman Brothers and The Eagles, for instance. Just like William, he had a knack for listening to people that helped him score rare interviews with press-shy musicians like Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. In case it wasn’t evident by now, Crowe genuinely loved the music he wrote about. It’s blatantly obvious in the choice of music he references in the script. Here’s one example:

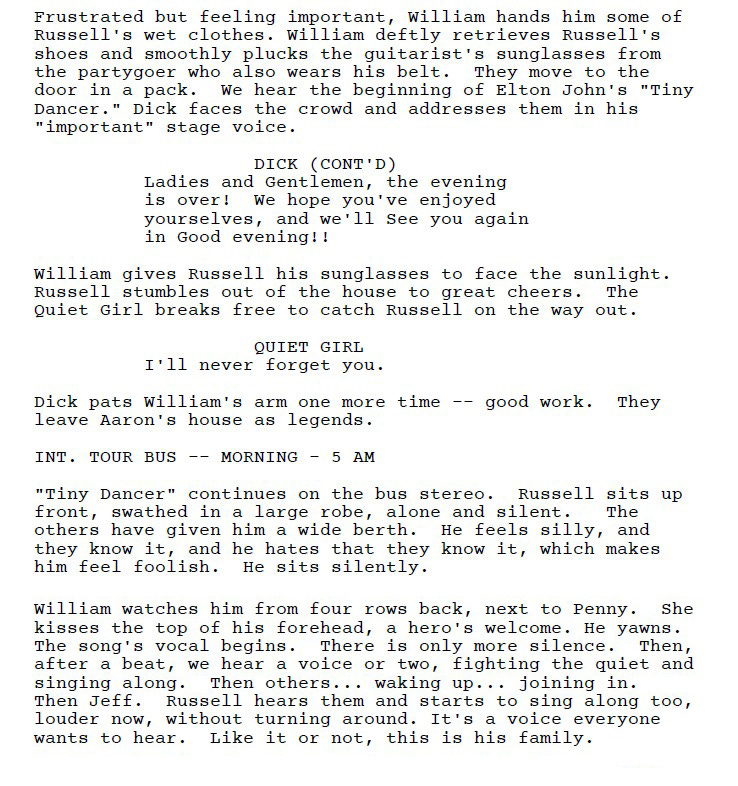

After all, it is a story about music. But Crowe goes beyond by being specific. Sometimes, it might be just to indicate what a character is listening to. But sometimes, it serves a purpose in the story—notably, the use of Sir Elton John’s ‘Tiny Dancer’ for a scene in which the band members put aside their animosity and heal the rift by belting out the song together.

I also like how he uses Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘America’ to explain the reason behind Anita moving out of the house and away from her mother.

Crowe’s journalistic training is evident in his writing. Catchy descriptions…

His lack of hesitation to drop paragraphs of descriptions when needed, as well as the poetry in describing how the image should look. When the characters speak, they speak like actual people— with feeling and character. He strikes the right balance between poignancy and humor in vulnerable moments.

The fact that the Almost Famous screenplay clocks 165 pages makes it a little daunting to read. Plenty of scenes indicated here were probably trimmed for a theatrical version. Likewise, the ending of the film plays out differently from what’s on the page. In the script, Russell visits Rolling Stone headquarters to convince the editors to run William’s story after they canned it; in the film, Penny Lane tricks Russell into visiting and apologizing to William, and granting the young boy the elusive interview that he’d been chasing since the assignment began. The script also does not have the scene where Penny Lane finally fulfils her dream to visit Morocco, as she mentions in the script.

The upshot is that the versions in the film are stronger than what is here— paying off the setups planted early on in the script.

Mining one’s childhood for movies is nothing new, but Almost Famous may have been one of the earliest examples from the 21st century to do it in a mainstream way. Two decades later, Steven Spielberg would do the same to make The Fabelmans; so would Celine Song with Past Lives; and Joanna Hogg with The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part II. The line between fiction and fact in Crowe’s screenplay, however, is less defined since it features real people such as Bangs and Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres; meanwhile, Penny Lane was inspired by one of the original Band-Aids, Pennie Anne Trumball. The overall result, however, is a rich script that, even despite some of its shortcomings, deserved to win the Academy Award and BAFTA Award for Best Original Screenplay. The very fact that it’s so personal is what makes it so original. To quote none other than the story’s protagonist, William Miller: Way to go.