A Separation (2011) Script Review | #66 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A subtle and powerful portrayal of how a marriage slowly disintegrates from a death by a thousand cuts, both from within and from outside.

Logline: A married couple are faced with a difficult decision – to improve their child’s life by moving to another country or stay in Iran and look after a deteriorating parent with Alzheimer’s disease.

Written by: Asghar Farhadi

Pages: 143

No social institution offers as much dramatic potential than marriage. In A Separation, this cleverly constructed and deeply heartfelt screenplay about a married Iranian couple at an impasse, Asghar Farhadi wrings every ounce of it.

A Separation, as the title indicates, revolves around Nader and Simin, a middle-class progressive couple. It opens, with minimal fuss, in a divorce court room where husband and wife lay out their respective arguments to the judge who remains unseen throughout the scene. Simin has received an opportunity for a residency in an unnamed foreign country but Nader cannot leave his ailing faither behind. As a result, Simin wants a divorce so she can take their daughter, Termeh, with her. Nader doesn’t want a divorce but he won’t give permission to take Termeh, knowing that Simin won’t leave without her. The judge is a little perplexed and slightly annoyed because Simin’s reasons for divorce don’t have grounds— Nader isn’t abusive, an addict, or doesn’t withhold money— so he tells them to go back to their lives.

But Simin moves out to go stay with her parents temporarily, while Termeh opts to stay with her father and grandfather, Mr. Morteza. The outcome and fate of Simin’s and Nader’s marriage is the A-plot; the B-plot or subplot kicks in around page 8 when Nader hires a conservative working-class woman, Razieh, to clean the house during the day and keep an eye on his father. Razieh is pregnant, and comes to work with her little daughter, Somayeh. She’s not in a state to be working and she becomes distressed on her first day when Mr. Morteza soils himself and needs to be cleaned— which wasn’t part of the arrangement. But it becomes apparent that she needs the money badly when she suggests sending her husband, Hojjat, in her place— when Razieh asks Nader to pretend she hasn’t worked at their house before, though, it’s obvious that her state of marriage isn’t exactly stable.

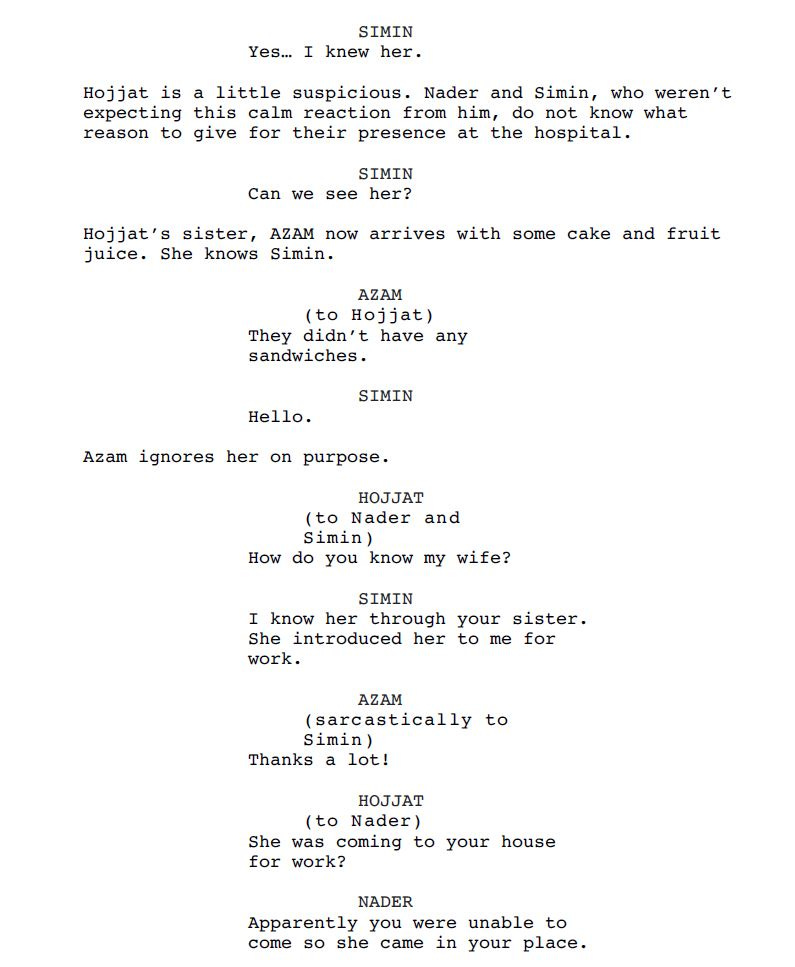

Alas, trouble! The next day, it is Razieh who turns up because Hojjat is dealing with creditors, and the following day, too. On her second day, she has to run out after Mr. Morteza gets out and tries to cross the street; on the third day, Nader and Termeh return home to find Razieh missing and Mr. Morteza in a bad state, having fallen off the bed despite his hand being tied to it. Tempers flare, accusations of missing money fly, and when Razieh won’t leave until she gets paid, Nader roughly shoves her away from the door. The next thing he knows is that Razieh is in the hospital, having suffered a miscarriage. On page 58-59, Hojjat realizes why Razieh ended up in the hospital, and he ends up pressing charges against Nader.

The couples in the A-plot (Nader and Simin) and the B-plot (Hojjat and Razieh) serve as mirror images— socially, economically, and personally. Even though they are on the verge of divorce, it’s clear that Nader’s and Simin’s marriage is built on trust and respect; they’re both well-educated and have good jobs— he works at a bank, she teaches languages— and religion doesn’t seem to dictate their entire lives; on top of which both parents, Nader in particular, is involved in Termeh’s education and in small life lessons such as making her pump the car gas and getting the exact change back from the attendant.

[insert]

Compare them, now, with Hojjat and Razieh. They’re both religious (and this will play a critical role in the climax), and there are hints that they fight a lot; perhaps even that Hojjat hits her. Hojjat has lost his job but he doesn’t like the idea of his wife working, never mind that he hasn’t been able to find employment. Divorce would be unthinkable to them, but I doubt that one could call their marriage happy or successful either.

Still, despite the clashes, Farhadi never favors a side; instead, he focuses on their humanity, allowing you to empathize with everyone to the point where you just want to find the best solution and get this over with. Nothing about A Separation is easy; Farhadi is uninterested in offering answers. He prefers to pose questions and leave it up to you to reach your own conclusion.

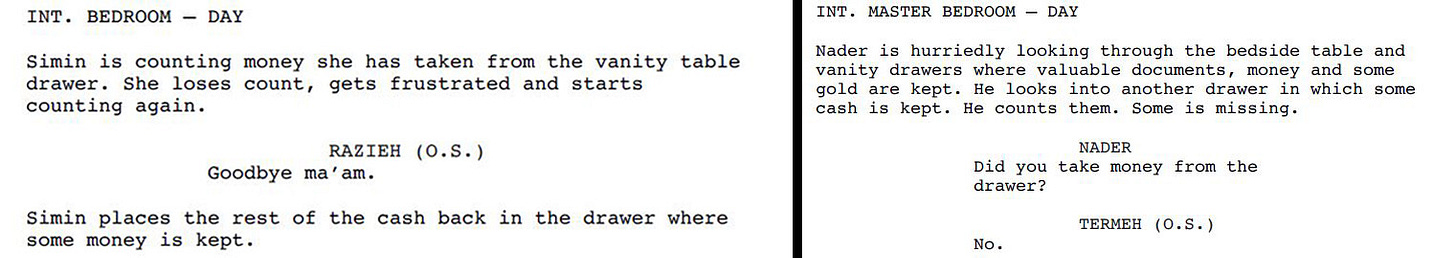

Some of these questions add tension to the story: Was Nader really responsible for causing Razieh’s miscarriage? Did Razieh really steal money as Nader accused her of doing? Was Nader ignorant of Razieh’s pregnancy as he claims, or did he know? Will this crisis help Nader and Simin reconcile, or will it destroy them?

Drama, unlike other genres, doesn’t have the obvious hooks and devices to create tension, and this forces the writer to come up with ways to create mystery and suspense to keep the audience invested. One way that Farhadi accomplishes this is, as mentioned previously, by generating questions in our minds. Another way is through its construction, planting key points in the story subtly with unexpected pay offs. Take, for instance, Nader’s accusation that Razieh stole money. What he doesn’t know- and what we realize only later- is that Simin used the money to pay extra to some piano movers without telling Nader.

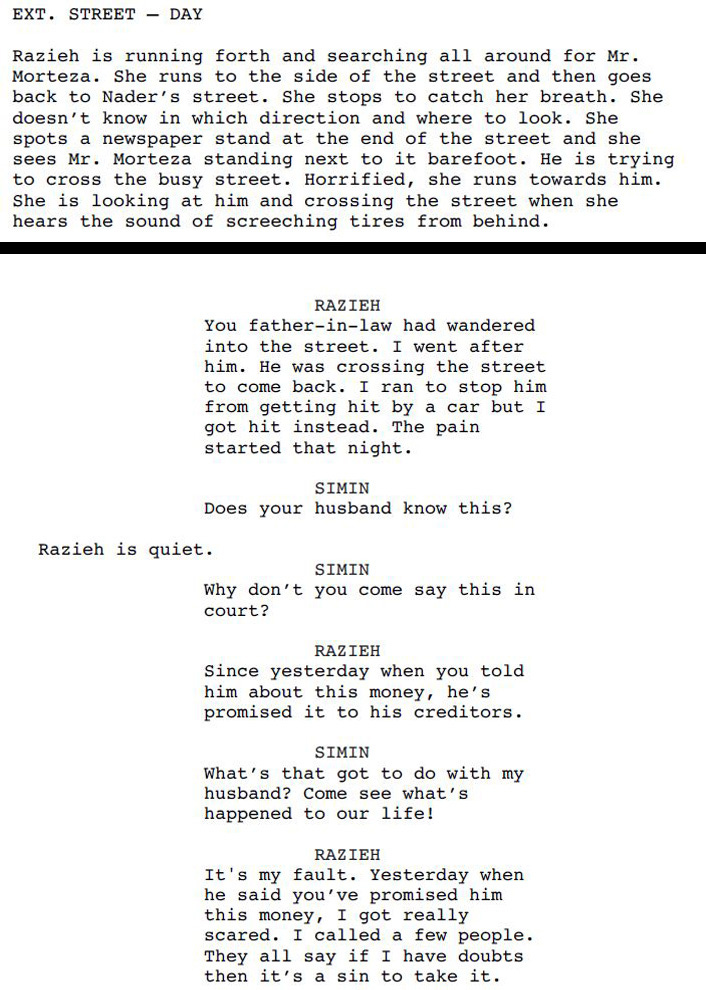

Likewise, the scene where Razieh rushes to stop Mr. Morteza off the street becomes a key point later when Razieh confesses to Simin later that on that day, a car knocked her; as a result, she went to see a doctor the following day to check on the baby, accounting for her absence when Nader and Termeh returned.

Asghar Farhadi began his career developing stage plays for Iran’s national broadcasting corporation, and his theatrical influence is apparent, for there are times when the screenplay’s arrangement echoes a play. Moreover, Farhadi’s influences include many great playwrights such as Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen, Tennessee Williams, and Samuel Beckett, as well as Iranian writers such as Sadeigh Chookak, and Mahmoud Dolatabadi. Indeed, his undergraduate thesis was on none other than Harold Pinter! This background suddenly illuminates the inner workings of A Separation. Observe that it is the pride of both men that escalates the conflict; observe that is their wives who find a way to break it; and observe that, in the end, it culminates in nothing but tragedy.

It'd be easy to assume that Farhadi started with these grand ideas and themes and found a story to slot them in; nothing could be further from the truth. Instead, he begins with the story and then, over the course of working on the material, will discover the themes and ideas emerging. For A Separation, he drew from a mix of numerous personal experiences and abstract pictures. As for the writing of the script, the one available online is clearly a translation, but otherwise, it appears that scriptwriting in Iran isn’t that different from Hollywood. Farhadi has a particular style, however— he keeps his action lines brief, but will write a short paragraph to create impact moments that are designed to land like a ton of bricks.

And structure matters. A Separation has all the elements lined up, allowing the story to go off with clockwork precision. The plot itself is simple, allowing more time for the characters.

To write a good dramatic screenplay, find the story and conflict first, build up the mystery by planting questions in the reader’s mind, and find opportunities to reveal the characters’ humanity. The result will be a drama as gripping as the best thriller. Just because you can’t have action sequences doesn’t mean you can’t substitute it with well-defined conflict and stakes. The playwrights were doing it for centuries before the Lumiere brothers helped pioneer a new medium. A Separation is proof of what excellent drama can look like.

Notes: