12 Years A Slave (2013) Script Review | #54 WGA 101 Greatest Scripts of the 21st Century

A harrowing and unflinching true story about a free man tricked into twelve years of brutal slavery.

Logline: In the pre-Civil War United States, Solomon Northup, a free black man from upstate New York, is abducted and sold into slavery. Facing cruelty as well as unexpected kindnesses Solomon struggles not only to stay alive, but to retain his dignity. In the twelfth year of his unforgettable odyssey, Solomon’s chance meeting with a Canadian abolitionist will forever alter his life.

Written by: John Ridley

Based on: Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup

Pages: 123

Scenes: 169

When Bianca Stitger first picked up a copy of Solomon Northup’s memoir, she opened it without much expectation. A few pages later, she could not say the same. She read it everywhere she went, while reading or cooking, even when putting the children to bed. Mostly, she read in disbelief: How could this have happened? How could human beings do this to each other?

In 12 Years A Slave, the answer is chillingly simple. Reduce a human being to a term such as “property” or “debt,” argue that slavery is justified under religious norms— in this instance, Christianity— and economic norms, and you would be surprised at how much cruelty you can inflict on an individual.

This was Solomon Northup’s experience.

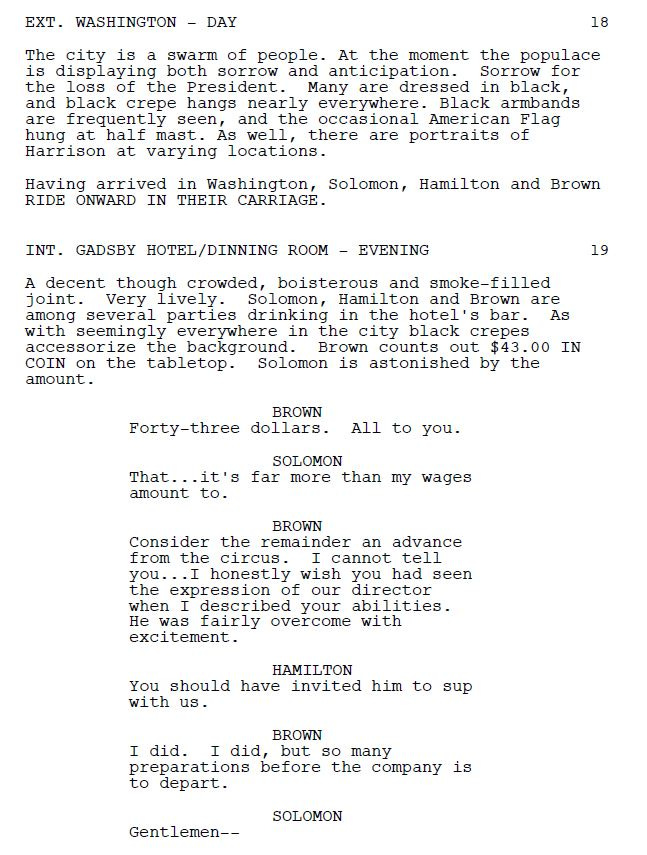

Solomon Northup was a free man in 1841. A talented violinist, he lives with his wife, Anne, and their two children, Margaret and Alonzo, in the North. When his family goes away on a trip, Solomon is invited by two men to travel with them to New York and earn money from playing the violin. Despite being a free man, making a living as a black man was not easy, and extra money would have tempted Solomon. Consider this almost throwaway line of dialogue confirming as such:

In a moment of grave consequence, he decides not to write a letter to his wife explaining where he has gone. It’s a decision that he will come to regret, and a moment written with poetic gravity.

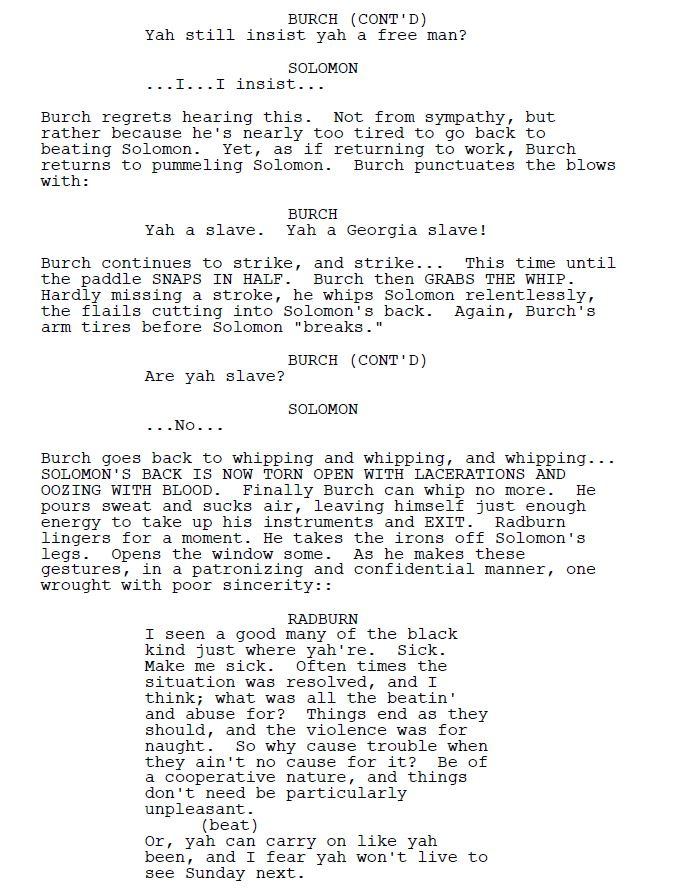

For on his last night in Washington, Solomon is coaxed by the men, Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, into toasting their success. Solomon is violently sick, passes out, and wakes up in a dungeon. Bound in chains, papers stolen, he has been sold to slave traders by Brown and Hamilton. Solomon is falsely accused as a runaway slave from Georgia; when he refuses to accept the narrative, the men violently whip and beat him.

Nothing about 12 Years a Slave is easy. That it’s based on a true story makes it only harder to fathom. It is the rare screenplay to actually depict the system of slavery as it really was, and told from the perspective of the enslaved— in all its brutal and dehumanizing glory. Writer John Ridley does not sanitize or sand down the jagged edges of the system to make it palatable, almost as if daring you to look away.

For the remainder of Act One, Solomon is convinced that he can escape. Other slaves he will encounter in the ensuing pages— Clemens Ray, John Williams, and Eliza— are resigned to their fate. Solomon’s hopes fade, too, as they are transported to New Orleans and is forced to accept his new circumstances.

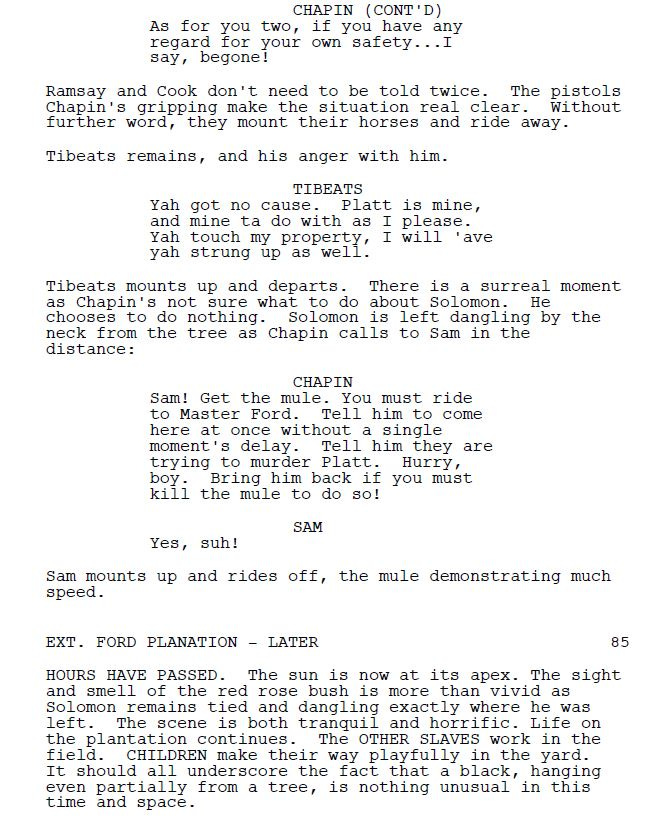

Act Two runs for 72 pages, from page 30 to 102. It spans seven years of Solomon’s captivity. Initially, it seems like Solomon may be alright, as he is sold to William Ford, a decent man who is not unkind yet still participates in owning slaves to enrich him. Solomon’s intelligence and talents endear him to Ford. But this brief period of decency is struck short by page 50, when Ford is forced to “sell” Solomon to his carpenter, Tibeats, because he cannot settle his debts.

It does not last long. An altercation erupts between Solomon and Tibeats, and the former is almost lynched for it in a scene that is hard to stomach.

As a result, Ford transfers the “debt” to another plantation owner called Edwin Epps; though he may as well have condemned Solomon to Hell. Epps is a demon. This occurs at the Midpoint and answers a question I’ve long wondered: yes, you can introduce new characters after the halfway point!

It is under Epps that Solomon begins to endure the most brutal years of his captivity— whipped regularly for failing to meet the daily cotton-picking quota, transferred between properties during bad seasons, and forced to helplessly endure the viciously deteriorating condition of a slave woman named Patsey. Close to the end of Act Two, Solomon glimpses a brief window of opportunity to escape by sending a letter through a seemingly friendly white man named Armsby, only for Armsby to give him away. Only quick thinking saves Solomon’s life from Epps, but he abandons any hope of ever seeing his family again. This is the Low Point of the story.

When Act Three begins, five years have passed. Solomon works on a building site with a Canadian abolitionist, Samuel Bass. Bass openly opposes slavery, which leads to Solomon taking another chance to confide in Bass. Though concerned for both their safety, Bass writes letters to Solomon’s family and it eventually leads to his freedom in a cathartic moment. A real one-in-a-million happy ending, though at great cost. When he returns home, he discovers that his children have grown into adults, and he has a grandson. Twelve years gone.

Although the script is linear, the filmed version adopts a non-linear approach, especially in the beginning. The writing is powerful, and I wonder if Ridley borrowed any of the real Solomon Northup’s lines from the book when writing. He captures the dialect and cadence of slaves and Southerners effortlessly…

… and builds scenes with slow yet unstoppable momentum.

Even before Stitger finished the book, she’d rushed upstairs to tell her husband, Steve McQueen, that she’d found the story he had been looking for. At the time, McQueen and Ridley—who’d met at a screening of McQueen’s Hunger— were searching for a project to collaborate on about slavery. Particularly, McQueen wanted to tell it from the point-of-view of a slave. In Northup, he found a character that had been a free man and a slave. Stitger had found the perfect material that met McQueen’s and Ridley’s requirements. Together, they created a harrowing and realistic depiction of America’s great shame— a system that is still perpetuated subtly through incarceration. Reading 12 Years A Slave will leave you queasy. As it should.

(Note: In somewhat unfortunate circumstances, the two had a falling out over screenplay credit. Although Ridley is credited as the sole writer, McQueen had asked for shared credit, but was declined. The cold war between the men was most noticeable at the 86th Academy Awards, when Ridley omitted thanking McQueen in his acceptance speech for Best Adapted Screenplay, and McQueen failed to mention Ridley when he accepted the Oscar for Best Picture. Ridley later expressed regret for not mentioning the director in his speech.)

Notes:

Cremers, Roger (10 January, 2014) | 12 Years a Slave: Bianca Stigter on finding Solomon Northup (The Standard)

Thompson, Anne (19 September, 2013) | John Ridley Talks Writing ‘12 Years a Slave’ and Directing Hendrix Biopic ‘All Is By My Side’ (Indiewire)

Gross, Terry; Mosley, Tonya (24 October 24, 2013) | ‘12 Years A Slave’ Was A Film That ‘No One Was Making’ (NPR)

Sneider, Jeff (3 March, 2014) | Oscars: ‘12 Years a Slave’ Screenplay Rift Between Steve McQueen, John Ridley Boils Over (TheWrap)